Guiseppe M. Bellanca came to the United States in 1911 with a degree in engineering and little else. By 1927, he had founded Bellanca Aircraft Company, and had already designed aircraft that held the world records for distance and endurance. Bellanca aircraft became well known around the world for their efficiency and utility. The Bellanca Aircraft Company continued to build aircraft from 1927 until 1955. Bellanca designs survived after that, however, passing through the hands of many companies, some of them carrying on the Bellanca name. But during those many years, very few Bellancas were ever built as military combat aircraft, and only two of those types reached production status. Amazingly, both of those designs served in Latin America!

The first of these unusual warbirds began life as a specially designed long-range racer. The Bellanca 28-70 was designed and built for Colonel James Fitzmaurice of Ireland. Fitzmaurice planned to race the 28-70, which he had christened The Irish Swoop, in the 1934 MacRobertson Race from England to Australia. The Irish Swoop arrived in Great Britain barely in time for the race, but Fitzmaurice withdrew after the MacRobertson rules committee limited his fuel load because of incomplete testing of the new aircraft. The 28-70 was returned to the United States to finish its testing, but was badly damaged in a landing accident. In 1936, the aircraft was rebuilt with a more powerful engine and was redesignated the 28-90.

Bellanca designations have proven difficult to understand, but were based on the aircraft’s specifications. In this case, the 28 indicated the wing area (280 square feet) and the 70 represented the power (700 horsepower). When the airplane received a 900 horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp during its rebuild, its designation naturally had to change as well. The airplane was also renamed The Dorothy and was flown by James Mollison to achieve a new trans-Atlantic speed record. In 1937, Mollison flew to Madrid, where The Dorothy was sold to the Spanish Republican government, which was desperate for any modern aircraft to help fight their civil war. Legend has it that The Dorothy was lost in combat during a reconnaissance mission (although historians are not truly sure what happened.)

Meanwhile, the Spanish Republicans had been impressed with the fast, long-range Bellanca even before the arrival in Madrid of The Dorothy. Late in 1936, they contracted with Bellanca to build twenty 28-90s for delivery in 1937. Because of a then-current United States law prohibiting the sale of arms to nations at war, the true buyer of the Bellancas had to be hidden. So, it was said that the aircraft were for Air France as long range mail carriers. The ruse went so far as having Air France insignia and titles painted on. By the time the twenty aircraft were completed, the game was up and export permission was denied. Amazingly, a Chinese Purchasing Commission bought the aircraft for use in their war, and the U.S. government had no objection to that! The twenty aircraft arrived in Hangkow, China, later in 1937, where bomb racks were fitted. Most of these Chinese aircraft were destroyed by Japanese air attacks before their first combat mission.

Bellanca got one more order for the 28-90 (which Bellanca had meanwhile named as Flash). Twenty-two aircraft were to be built for Greek civil reserve aviation school. But, this export license was again denied because the aircraft were actually headed for Spain again! The Bellancas were eventually shipped to Mexico after an American exporter got permission to sell them to the Mexican government. In fact, the intention was to load them aboard a ship in Veracruz for shipment on to Spain. But, before the Bellancas could be loaded aboard ship, the Spanish civil war was over, and the Republican government, who had ordered the Bellancas, was defeated.

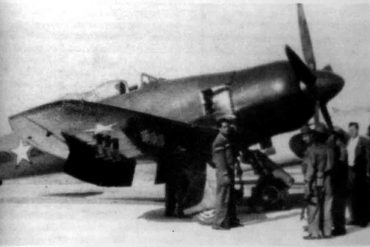

For an entire year, the aircraft sat in their shipping crates in a Veracruz warehouse while negotiations went back and forth between Mexico and Spain. Two of the major negotiators were Colonel Gustavo León and the aviator Juan Ignacio Pombo (famous for his Santander – Mexico Atlantic crossing.) There are several different versions of exactly how the negotiations went but, at any rate, the Bellancas passed into the ownership of the Fuerza Aérea Mexicana -FAM- (Mexican Air Force), and the airplanes were assembled in late August and early September, 1939. The first flight, conducted by Major David Chagoya and Colonel Alberto Salinas Carranza (at the time Commander of the FAM), took place on September 13 of that same year at the Balbuena Airfield. Unfortunately, the very next day one of the airplanes crashed near Tulpetlac, killing Major Raúl Azcarate Pino and leaving his copilot severely injured.

Even though the cause of the accident of Maj. Azcarate was determined to be a mechanical failure, the local press blamed the FAM pilots for their lack of experience on the aircraft. In fact, Capt. Enrique Velasco Rivas, member of the 1st Regiment -which was the FAM unit that flew the 28-90s- had to send letters to a couple of newspapers denying such accusations, stating that all the aviators assigned to that aircraft type had received proper training in the U.S. However, less than a year later, on August 21st, 1940, a second Flash crashed while attempting to land at Balbuena, killing Lt. Manuel Peña Ávalos and Capt. Enrique Ochoa, who was in the backseat acting as observer. According to other pilots who witnessed the accident, Lt. Ávalos lost control of the airplane just seconds before touching down. Both, Ávalos and Capt. Ochoa were thrown clear out of the cockpit and died instantly. (After a thorough investigation, it was determined that Lt. Ávalos had confused the flap and landing gear levers during approach.) In any case, that accident sealed the fate of the 28-90s with the Mexican air arm and, not long after, the airplanes were grounded, with most of them placed in storage while a few were destined to be instructional airframes for the training of mechanics.

It wasn’t until 1946 that Babbco, Inc., the Mexican affiliate of Charles E. Babb Company, bought the surviving 28-90s and attempted to sell the -by then- very obsolete aircraft to the U.S. Navy as instructional aircraft. Thus ends the curious tale of the Bellanca Flash with the Mexican Air Force.

During their rather short service with the FAM, photographic evidence shows the 28-90s wearing a very plain paint scheme of olive drab over neutral gray. No photos show any serial numbers or even FAM insignia on the aircraft, even though there are accounts -mainly from pilots who flew them- that at one point, the aircraft had the FAM roundels and serials painted on. Hence, we have included in this article, both color profiles. However, if anyone has photographic or anecdotal evidence of a different paint and marking scheme for these Mexican Bellancas, please send them our way pronto!

The other Latin American Bellanca warplane was also the only one designed from the outset as a warplane to reach production status (however limited). This was the Bellanca 77-320. The 77-320 was actually designed by Bellanca to fulfill a Colombian requirement for a tough, utilitarian seaplane bomber. Such design was based on that of the successful Airbus/Aircruiser series of Bellanca transports. These single-engine transports were more-or-less the culmination of Guiseppe Bellanca’s theory that every surface of the aircraft should -if at all possible- contribute to the production of lift. This meant an airfoil-shaped fuselage and wide, airfoil-section bracing struts. The 77-320, though a twin-engine design, inherited these unique identifying features. If you saw one of these bombers once, you never mistook it for anything else in the sky!

Four 77-320s had been ordered by the Colombian Aviación Militar (Military Aviation) at the height of the Leticia Conflict with neighboring Peru. The war was concluded (favorably for the Colombians) on June 25, 1934, but the Bellancas had still not arrived. The prototype had flown in Delaware in 1934, but was destroyed in a hangar fire. Hence, the four production 77-320s arrived in Colombia until the next year.

The Bellanca 77-320 was a twin-engine, high wing (some would say sesqui-plane, based on the huge lifting struts) bomber. Powered by two 715 horsepower Wright R-1820-F engines, the airplane carried five .30-calibre defensive guns in nose, dorsal, ventral and twin lateral positions. Offensive armament could be a mixture of 100- and 300-pound bombs on stub wing racks and 600- and 1,100-pounders on the fuselage racks, for a total of up to 2,200 pounds. The 77-320 was equally adept at a number of missions other than bombing, including photogrammetry, troop transport, medical evacuation or freighter. Construction of the bomber was a mix of steel tube covered with fabric and metal panels for the fuselage, tail, and inner wings, with the outer wings and horizontal stabilizer being constructed of wood. The 77-320s, though sturdy and efficient, were quickly overtaken by events. When Lend-Lease equipment began arriving in Colombia in 1942, these bombers were quickly retired.

Photographic evidence shows the Colombian 77-320s operating in a light colored all-over paint scheme, that is probably aluminum dope (although it could easily by white, light gray, cream or some other light shade of paint.) Photos also show the 773-320s carrying the complex Colombian roundel on the vertical tail as well as underwing (probably over the wing, as well), but with no serial number or other markings. Again, if anyone has more evidence of paint schemes and markings for these aircraft, please forward them to us. We’ll really appreciate it!

This is an updated version of the article originally published on October 5, 2003. Our sincere thanks to Santiago Flores for his invaluable help.