By the middle of 1960, the novelty of Fidel Castro’s Cuban Revolution was wearing thin and many of those who had first zealously supported him began to leave for the United States. Scarcely more than a year after Castro had unseated the dictator, Fulgencio Batista, the American government under Dwight D. Eisenhower was making plans to overthrow the bearded leader and the influx of discontented Cubans offered a ready-made invasion force – with a little help from their friends, the Central Intelligence Agency.

The story of the battle which took place on the beaches of Girón and in the Zapata Swamp has already been well documented. In contrast, the intention of this article is to offer an insight into the defensive operations from the standpoint of the multi-national Cuban Revolutionary Air Force (Fuerza Aérea Revolucionaria – FAR) – something which appears to have been steadfastly avoided, by all parties, for over 40 years.

The Men

In the pre-dawn hours of April 15th, 1961, a force of Douglas B-26 bombers1 initiated a series of surprise attacks against Cuba’s three major military airfields: Ciudad Libertad (formerly Camp Columbia) in Havana, San Antonio de los Baños, southwest of the capital and Antonio Maceo International Airport at Santiago de Cuba, at the country’s eastern tip. The attacks were intended to be pre-emptive, effectively rendering the island nation defenceless against the coming land and air assault by almost 1500 CIA-backed guerrillas.

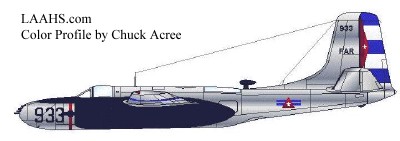

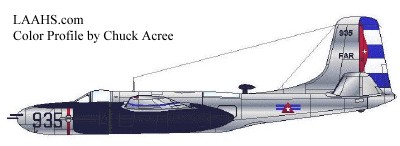

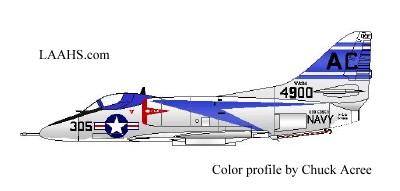

“The attacking aircraft were reasonably identical to those used by the FAR and carried essentially the same national insignia and markings. This attempt at confusing the defenders worked to some degree but would have been more effective if the insurgent machines had not also been decorated with broad blue wing stripes, to safeguard them from attack by their own forces. One also suspects it would have been better if their intelligence had told them that FAR aircraft were currently wearing two-tone camouflage, not natural metal schemes!”

Lt. Alberto Fernández, flying a Lockheed T-33A armed with two M3 machine-guns, was the first pilot to get airborne during the attack on San Antonio and the only one with any reasonable chance of catching the attacking aircraft. On guard duty when the first explosions occurred, he ran for aircraft ‘715’, but it took a direct hit and disappeared before his eyes. Choosing a second aircraft, he got airborne as quickly as he could but the B-26s had hit hard and fast and were out of visual range before he could intercept them. Lt. Gustavo Bourzac, a Hawker Sea Fury FB.11 pilot, probably made air combat history by being the first man to scramble against enemy forces wearing only his ‘jockey’ shorts. Awakened from a sound sleep, he wasted a few seconds looking for his flight suit and parachute and then simply raced to the flightline and jumped into the first available aircraft. Like Fernández, although he searched as far south as the Isle of Pines (now the Isle of Youth), he was too late.

Incredibly, there were no further air attacks. In fact, the main invasion force did not arrive on the beaches of the southern coast until the 17th, giving the Cuban Air Force two complete days in which to prepare for the coming fight. While pilots sat ready in the cockpits of the serviceable aircraft – a T-33A, 2 B-26s and 2 Sea Furies – the technical staff worked feverishly to bring others up to flying standard. By the end of hostilities, 4 Sea Furies, 5 B-26s and 5 T-33As had seen action.

In time, the Cuban Air Force would become the most powerful in the Caribbean and Latin America, but at the moment of these first attacks, it was but a pitiful shadow of a true military force. Pilot training was almost non-existent, given the fact that virtually all aircraft in the inventory were unserviceable. Those aircraft that could be flown were only barely capable of air combat missions – even if there had been adequate stores of starter cartridges, spare parts and ammunition.

None of the pilots had flown at night – they had no radar. None of the pilots had undergone any real combat training either, and only a select few had ever fired their machine guns, much less a 5″ rocket. However, in his book “Operación Puma“2, Brigade pilot Eduardo Ferrer acknowledges the skills and experience of the three eldest defenders: Enrique Carreras Rolas, 38 – qualified on props, jets, fighters, bombers and transports, with 5000 hours accumulated, including advanced training in the United States; Luis Silva Tablada, 35 – an experienced bomber pilot with 4000 hours, also including advanced training in the U.S.; Alvaro Prendes Quintana, 32 – an experienced fighter pilot, with 2000 hours. 27 year old Douglas Rudd had been training in the U.S. in early 1959, but the other younger pilots, Rafael del Pino, 22, Alberto Fernández, 24 and Gustavo Bourzac, 27, were relatively inexperienced.

Aside from these native Cubans, the roster also included three Nicaraguans – Álvaro Galo, Carlos Ulloa and Ernesto Guerrero, as well as a handful of Chileans, including Jack Lagás, who had been contracted to provide training. Rafael del Pino had to be recalled from his duties as Deputy Commander of the Mariel Naval Base, west of Havana, where Douglas Rudd had recently completed five months in a non-flying post. Alvaro Prendes had just returned from three months of infantry duty in the Escambray mountains, where he had participated in actions against gangs of counter-revolutionaries.

The state of repair of the Cuban Air Force aircraft, inexplicably, had not been a high priority for the Cuban High Command and Captain Evans Rosales, Chief of Maintenance, came close to paying the price for that lack of concern. On the afternoon of April 16th, as a result of grounding all aircraft for not meeting minimum standards to guarantee crew safety and furthermore, putting his report in writing, he was arrested and charged with high treason. When he finally came to trial, the single greatest piece of evidence against Rosales was the fact that the pilots and crews had proceeded to defeat the incoming force, with surprising ease and a minimum of losses. If there had been any truth to Rosales’ assertions, these events could hardly have transpired, as far as the government was concerned. Initially condemned to the firing squad, he was eventually reprieved and freed as a result of the intercession of the pilots that he had attempted to safeguard.

In spite of all the foregoing concerns, four things would eventually work in favor of what can best be described as a rag-tag air force:

- The initial attacks against the airfields included a waste of time, aircraft3 and explosives on Ciudad Libertad. It was, admittedly, the location of Air Force Headquarters, but was being used for storage by anti-aircraft and artillery regiments – there had not been a single aircraft stationed there in months. The main field at San Antonio could have been utterly destroyed, with the loss of all resident Cuban Air Force aircraft, if the CIA’s intelligence group had thought this out more carefully. This was a critical error in consideration of the fact that the Brigade B-26s had no rear-firing turrets for defence. (These had been removed in the interests of bomb load and fuel.) With only eight fixed forward-firing guns, they were no match for the faster, more maneuverable T-33s.

- John F. Kennedy (the arguments will go on forever) refused to provide the air cover that Eisenhower had promised to the invading ground troops of Brigade 2506, reducing the number of attacking bombers by half and chose not to send a second wave.

- The Cuban pilots were possessed of more patriotic fervor, determination, audacity, ability and just plain guts than the Americans gave them credit for.

- To this day, the Cuban mechanic, aviation or automotive, is endowed with a genius that defies the imagination. The ground crews of the Cuban Air Force proved themselves worthy of the highest award their country could offer for the successful completion of a monumental task, in the face of what should have been insurmountable odds.

Starting on April 17th, Cuban Air Force aerial operations were virtually non-stop during daylight hours and all aircraft were shared, with some pilots flying a T-33A on one mission and then a Sea Fury or B-26 on subsequent flights. During the course of four days of fighting, several aerial victories were recorded by the Cuban pilots, in spite of their relative inexperience in combat situations.

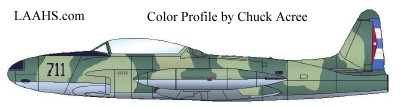

The first of these was scored very early on the morning of the 17th by Lt. Alberto Fernández in T-33A ‘711’. His victim, B-26B ‘635’, crewed by Matías Farías and Eddie González, crashed on the Girón airfield, not far from the hulk of the supply ship “Houston“. (Just prior to Fernández’s victory, Capt. Enrique Carreras and his wingman, Lt. Gustavo Bourzac, flying Sea Fury FB.11s, had crippled the “Houston“, the Brigade’s main source of arms and supplies.)

On his return to San Antonio de los Baños, Fernández took T-33 ‘703’ and went back to the beach head to seal the Houston’s fate. Shortly afterwards, Capt. Prendes, flying ‘711’, made several passes at an LCT off the shores of Playa Girón, where it ran aground. However, he had to return to base with an anti-aircraft cannon shell lodged in his right brake. One of Cuba’s most experienced pilots, he managed to bring the aircraft down safely and 40 minutes later, René Suárez and the other mechanics had the aircraft repaired and back in action. On his next sortie, Prendes severely damaged a B-26 which made an almost successful run for home, crashing a short distance from Puerto Cabezas in Nicaragua. Then, in the confusion caused by the enemy’s copycat aircraft, Prendes very nearly suffered the misfortune of shooting down one of his own. In fact, he had completed his first firing pass before he realized the aircraft was not sporting blue wing stripes.

“This was as much a matter of increased tension and adrenalin flow as anything – a not uncommon situation in wartime. At times, the brain is forced to work so quickly that it can’t possibly analyze all the input correctly. As an example of this, Rafael del Pino had a conversation with Alberto Fernández on the latter’s return from the action in which the Brigade B-26 ‘935’ was shot down, during which Fernández reported the destruction of a four engined aircraft!”

Carreras and Bourzac returned to the Girón area with one of the Nicaraguan pilots, Lt. Carlos Ulloa, to continue their attacks on shipping and Carreras was able to claim his first aerial victory, but not before taking anti-aircraft hits in his engine, port fuel tank and starboard wing. This mission resulted in one of two strange situations which arose involving cowardice in the face of the enemy. While the three Sea Furies were attacking the landing craft and ships, Capt. Luis Silva and Capt. Jack Lagás, in B-26s ‘937’ and ‘915’ respectively, strafed and bombed enemy positions along the beach while Capt. ‘Willy’ Figueroa was supposedly providing top cover for the bombers, in T-33 ‘711’.

Figueroa appears to have taken one look at the hail of anti-aircraft fire coming from the beaches and returned to San Antonio, never having fired a shot. He was arrested as he stepped from the aircraft. Around midday, Lt. Rafael Del Pino, in T-33A ‘703’, was ordered to provide top cover for Capt. Silva’s B-26 ‘923’ and Lt. Bourzac’s Sea Fury. When he arrived at altitude, some 3,000 feet above their expected position, he sighted a B-26 on a heading at a 50 degree variance from the flight plan. A quick radio check with Silva confirmed that the aircraft in view was, in fact, an enemy. Two passes and several bursts of machine gun fire were enough – the bomber disintegrated in the air.

Later that afternoon, Capt. Prendes (709) and Lt. Del Pino (711) were ordered to attack ground installations around Soplillar, using 250 pound bombs. During this mission, Prendes successfully downed one of a pair of B-26s that was en route to attack Cuban troops, but only after committing the near fatal error of challenging it head-on! The fire from eight heavy machine guns taught him an extremely valuable lesson, very quickly. Del Pino chased the second machine, raking it from tail to nose, but couldn’t bring it down. In fact, he became so focussed on his quarry that only a panicked radio call from Lt. Rudd saved his life. Del Pino came to his senses little more than 60 feet from the surface of the ocean and broke off the attack.

Rudd, on a solo mission in a Sea Fury, continued the pursuit and finally applied the “coup de grâce“, with the target eventually crashing near Guano Cay. During this encounter, Rudd was forced to retire by the appearance of two U.S. Navy A4D-2 Skyhawk fighters, which he later mistakenly identified as Douglas F4D Skyrays. There was no attempt by the Americans to engage the Cuban pilot – they simply tried to place themselves, too late, between him and his intended victim.

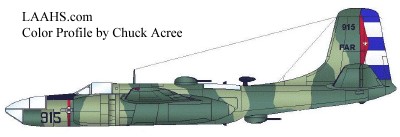

On an anti-shipping sortie on the 19th, Captains Carreras (711) and Prendes (709, possibly 703 – memories are failing and log books are not readily available) caught 2 enemy bombers coming out of a cloud bank in combat formation, with a full complement of rockets and bombs. Prendes broke left, Carreras right and in seconds, each had scored a victory. Of course, not every flight resulted in an aerial victory and something must be said about men like Jack Lagás, the Chilean B-26 pilot, who flew mission after mission in aircraft that probably should never have left the ground. For instance, he and his crew strafed Girón three times in B-26 ‘915’, disregarding the danger of fire from the port engine, which indicated extremely high fuel pressure. On his next mission, in ‘917’, an electrical short and a smoke-filled cabin forced him to make an emergency landing with four 500 pound bombs aboard. Eventually, the stress of operating under such conditions took its toll and he had to be relieved of flying duties.

It is unanimously agreed by the other pilots that Ernesto Guerrero, one of three Nicaraguans in Cuban service, completed four effective ground attack missions in a Sea Fury, during which he destroyed several targets, including a Sherman tank. Unfortunately records are incomplete and there is little data available on exact dates and times, aircraft used, etc.

Gustavo Bourzac (of the BVD’s), in the course of 8 missions over the four days of operations, shared in the kill of the “Houston” with Capt. Carreras, attacked and destroyed countless ground targets and was hit several times by enemy fire.

Unfortunately, no war is one sided and the defenders suffered their losses as well. Capt. Orestes Acosta was lost on the morning of the 15th while flying T-33A ‘707’ from his base in Santiago de Cuba and the circumstances of his death have remained a mystery to this day. While the enemy attacks were being carried out against the various airfields, word was received of a surface force moving toward Santiago. Ordered to make a reconnaissance flight over the area in question, Acosta was never heard from again. Conjecture is that since he was recovering from a serious illness and had previously suffered fainting spells, he passed out and simply fell into the sea.

As an indication of the determination of the Cuban pilots, Capt. Luis Silva was flying while under treatment for extremely painful stomach ulcers. He was, in fact, only a week out of hospital. His first anti-shipping sortie, in B-26 ‘937’, had been a success but he was shot down at Girón on his following mission, in ‘923’, with the loss of all aboard. The crew included Gunner Sergeant Martin Torres, Mechanic Reinaldo González Martínez and Navigator Alfredo Noa. In fact, it appears that he was, in a sense, his own victim. His aircraft was hit several times by anti-aircraft fire and apparently unaware that his fuel tanks had been ruptured, he fired a salvo of rockets, whose backflash caused an explosion. Lt. Carlos Ulloa, another Nicaraguan, affectionately nicknamed ‘Pollo‘ (Chicken) by his fellow pilots, was using machine guns and 5″ rockets to attack enemy supply ships when he was hit several times by their ferocious anti-aircraft defenses. His Sea Fury FB.11 exploded in the sea, on his first mission.

Over the course of four days, 10 pilots flew 70 missions, attacking shipping, ground forces and enemy aircraft, accounting for 2 ships, the “Houston” and “Río Escondido“, 8 confirmed B-26 kills and innumerable landing craft, tanks, trucks and anti-aircraft sites. Each and every one of the pilots involved would agree that their victory over the insurgents was due in large part to the efforts and ingenuity of the technical and mechanical staff – the armourers, refuelers and other ground crewmen who worked so frantically, often without sleep or meals, to keep aircraft fit and ready for combat. Their ‘innovations’ included fitting Buick brakes to B-26 bombers, repairing T-33A fuel systems with plastic hose and rebuilding injectors with silver solder.

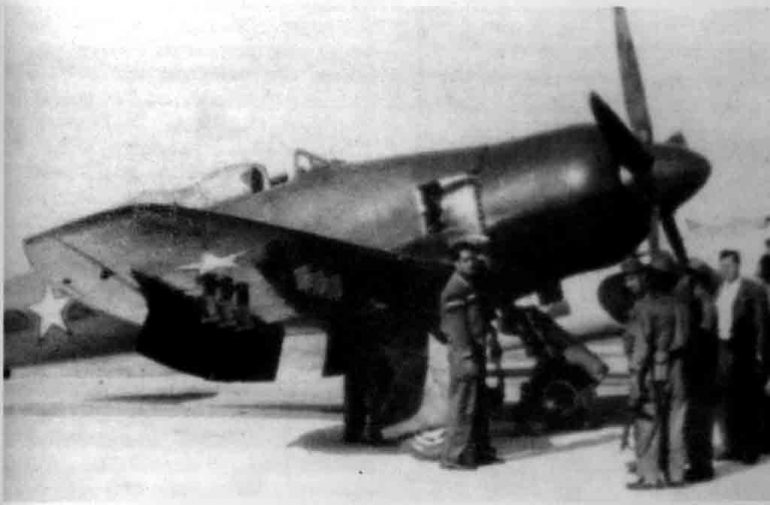

The Aircraft

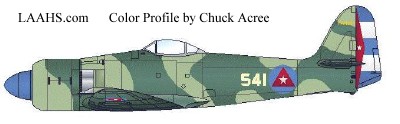

Four Hawker Sea Fury FB.11s were involved, three of which were fit for duty on April 15, serialled 541, 542 and 543. These numbers conflict with the normal pattern established for these aircraft, which was increments of 5, starting at 500. Thus, 500, 505, 510, etc. There is photographic evidence of the existence of 542 and my conjecture is that these three aircraft were, in fact, ‘new’ aircraft, constructed from the cannibalized remains of the original 15 FB.11s.

In fact, Carlos Ulloa, the Nicaraguan pilot who lost his life during the conflict, is stated to have been flying Fury 543 by several official sources. (Some confusion results from separate research undertaken by historian Jorge Fariñas, which indicates that Ulloa’s normal mount [from his correspondence to his family] was ‘545’.)

Douglas Rudd flew one (possibly 542 or 541) to Santiago de Cuba as a replacement for the T-33A lost there with Acosta. General Rafael Del Pino states in his book “Proa a la Libertad” that after Rudd left for Santiago, the technical staff succeeded in resurrecting yet another FB.11.

As mentioned earlier, five B-26s took part in operations:

- 909 was one of several flown by Jack Lagás.

- 915 was flown by Lagás and later by Carreras, who also suffered an electrical fire, which forced him to return to base before he could take part in what was essentially the final air attack of the conflict.

- 917 is the aircraft in which Jack Lagás was forced to make a fully loaded emergency landing.

- 923 was flown by Silva, a B-26 Squadron Commander, on his second and final mission.

- 937 was used by Silva on his first mission.

Lt. Álvaro Galo, an expatriate Nicaraguan, flew an unidentified B-26 to the beachhead at Girón, but panicked at the amount of anti-aircraft fire and refused to enter the zone. He was arrested on his return to base. The incredible irony is that his was the aircraft which Capt. Prendes came close to shooting down by mistake.

6 of Cuba’s original 8 Lockheed T-33As played some part in the operations:

- 703 was flown by Enrique Carreras, Alberto Fernández and Rafael Del Pino. Guillermo ‘Willy’ Figueroa also flew the aircraft but returned to base with all his weaponry intact and was summarily arrested for cowardice.

- 707 was lost on a reconnaissance mission with Orestes Acosta within the first few minutes of the April 15th attacks.

- 709 was piloted by Álvaro Prendes and Alberto Fernández.

- 711, the most active and best conditioned machine, was flown by Enrique Carreras, Álvaro Prendes, Alberto Fernández and Rafael Del Pino.

- 713 was shared by Fernández and Del Pino.

- 715 was destroyed as a result of a direct hit in the first wave of attacks against San Antonio de los Baños Air Force Base on April 15.

(With regard to the two remaining original T-33As, 701 was destroyed before the invasion, as the result of a training exercise flameout, with Del Pino and instructor Martín Klein at the controls; 705 exploded over the Escambray mountains in the late Batista era, while carrying a ‘home-made’ bomb, which detonated prematurely.)

End Notes

1 The invading B-26s were divided into three flights:

Puma Flight

Target: Ciudad Libertad, Havana

Puma One: José Crespo, pilot. Lorenzo Pérez-Lorenzo, navigator.

Puma Two: Daniel Fernández-Mon. Gastón Pérez.

Puma Three: Osvaldo Piedra. José Fernández.

Linda Flight

Target: San Antonio de los Baños Air Force Base

Linda One: Luis Cosme. Nildo Batista.

Linda Two: René García. Luis Ardois.

Linda Three: Alfredo Caballero. Alfredo Maza.

Gorilla Flight

Target: Antonio Maceo International Airport, Santiago de Cuba

Gorilla One: Gustavo Ponzoa. Rafael García Pujol.

Gorilla Two: Gonzalo Herrera. Angel López.

2 Most pilots from both sides were well known to each other. In fact, little more than a few months before the battle, they had been sharing the cockpits of Cuba’s civilian and military aircraft. The book “Operation Puma” is available in both English and Spanish and effectively relates the Bay of Pigs air encounters from the Brigade pilots’ point of view.

3 One Brigade B-26, ‘Puma Three’, was destroyed by anti-aircraft installations, crashing into the sea in front of the Comodoro Hotel. The starboard engine of a second aircraft , ‘Puma One’, was knocked out and the pilot was forced to make an emergency landing at Boca Chica Naval Air Station, on Key West, Florida.

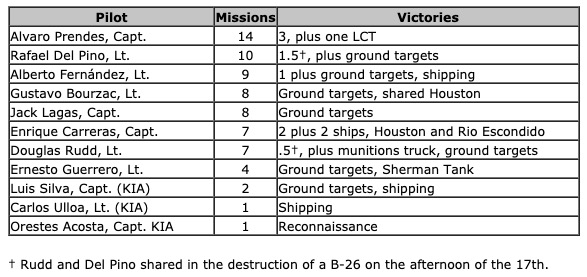

Cuban Air Force Pilots

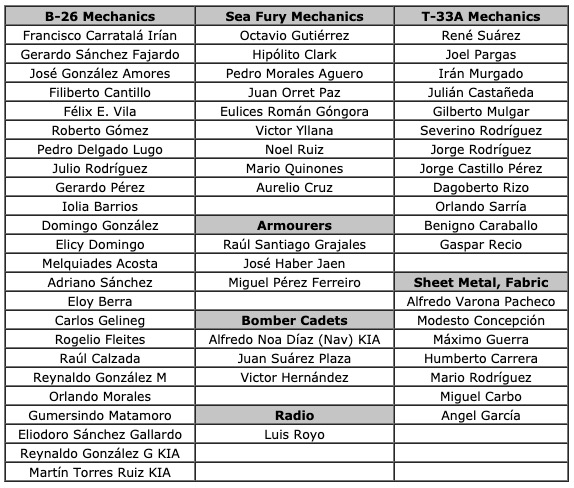

Cuban Air Force Ground Crews

Author’s notes

During the course of researching this topic, I had the great pleasure of meeting three of the defending pilots involved. I first met Álvaro Prendes Quintana at his home in Havana in 1992 as a result of an introduction by Capt. Orestes Del Río Herrera, the first commanding officer of the Fuerza Aérea Rebelde, the Rebel Air Force.

Col. Prendes, as he was when I met him, was typical of pilots everywhere – warm, friendly and ready to talk for hours about flying. Unfortunately for him, he was also typical in other ways. He was not a true dissident in the dictionary sense, but he did have the fighter jock’s habit of saying what he felt and when a letter to Fidel Castro, in which he requested democratic changes in the country’s policies, failed to achieve any positive results, he spoke to the foreign press about his views. These actions made him unpopular with his government, to say the least, and eventually, thanks to his position as a popular hero, he was granted permission to leave for the United States, where he currently resides.

Shortly after my first meeting with Col. Prendes, I was introduced, again by Capt. Del Rio, to then Brigadier General Enrique Carreras Rolas. My book, ‘Harvard! The North American Trainers in Canada‘, had just been published and acted, as it has so often, as an effective ice breaker. Both Del Rio and Carreras had logged many hours in these aircraft. Unfortunately for me, General Carreras was still on active duty, serving in the Ministry of the Armed Forces and I was not able to establish further meetings.

Most people interested in this subject will be familiar with the name of General Rafael Del Pino Diaz. After rising through the ranks to command the Cuban Air Force, he became so disenchanted with his country’s policies that he planned and executed a daring escape with his wife, two year old daughter and one of his adult sons. In 1987, he took off from Havana in a Cessna 402 which was at his disposal and never looked back. Chased by two MiG-23BNs from San Antonio de los Baños Air Force Base, he succeeded in reaching U.S. airspace before he could be intercepted. He now lives under the protection of the United States government.

Douglas Rudd died in Miami in early 1992 while visiting the home of Eduardo Ferrer, one of the air commanders of Brigade 2506. Later that same month, I was able to spend several enjoyable hours with Eduardo, although it was a huge disappointment to realize how close I had come to meeting another of the Cuban ‘few’.

Gustavo Bourzac died in Cuba. Jack Lagás died in an aviation accident in Chile. Alberto Fernández, when last I heard, still resides in Havana. Ernesto Guerrero originally returned to his native Nicaragua, but now lives in California.

References

– Book “Proa a la Libertad“, Rafael Del Pino, Editorial Planeta Mexicana, 1990.

– Book “En el Punto Rojo de mi Kolimador“, Alvaro Prendes, Editorial de Arte y Literatura, 1976.

– Book “Operation Puma“, Eduardo Ferrer, 1975. (English edition 1982.)

– Weekly Newspaper “Granma Semanal”, various editions.

Color profiles by Chuck Acree.

Awesome 👏

En el listado de mecánicos de Sea Fury no aparece el nombre de mi padre que era el jefe de linea de vuelos Sea Fury Base de San Antonio

su nombre era Tirso Campanioni Carmenate.

Tengo documentos que prueban está afirmación

Doug,

My name is Rolando Figueroa and I am the son of Willy Figueroa, the pilot you mentioned in your article. I would like to set the story straight. My father didn’t run away afraid of getting shot, he decided to return to base because this wasn’t a war… this was a blood bath. My father wasn’t a killer and didn’t want to have blood on his hands. He decided that this was the end of the line and wanted nothing to do with this attack.

Sorry for my innocence, but your father enlisted in an army and was sent to repel an invasion. He did not, so he was a coward. Or worse, if he assumed that the US-supported landing was not a war, or that he did not want to have blood on his hands (strange thing, if he is in the middle of a military invasion and you are a war pilot), he should not have taken The plane first. Sorry but your arguments don’t help your father.

He was asked by Raul Castro to go up and take a look at what was going on. Once he realized that it was just an amphibious attack he made the conscious decision to turn back and not fire on the poor souls coming in on zodiacs. My father attended Fork Union Military Academy in Virginia and knew half of his classmates where probably on those zodiac’s. My father wasn’t a communist and left the air force the moment he stepped foot on ground.

Your father did a great job by not participating in the defense of the dictatorship. You should be proud Rolando!

Thank you sir. Today is his birthday and he is 85 yrs old. I had the pleasure to be with him today.

To Rolando Figueroa.

Your father was a coward pure and simple. It’s hard to hear because he was your dad but it’s the truth no matter how he tried to spin it.

He was asked by Raul Castro to go up and take a look at what was going on. Once he realized that it was just an amphibious attack he made the conscious decision to turn back and not fire on the poor souls coming in on zodiacs. My father attended Fork Union Military Academy in Virginia and knew half of his classmates where probably on those zodiac’s. My father wasn’t a communist and left the air force the moment he stepped foot on ground.

Your father was a hero. He made a decision based on reality. He made a decision based on the sad reality of what was happening. Bless you and your family.

Thank you sir. Today is his birthday and he is 85 yrs old. I had the pleasure to be with him today.

A very good article I was a child living in Havana at the time of the invasion. My brother, a friend and I watched the exile B-26 aircraft fly over the city after bombing Camp Libertad formerly Columbia. Perhaps the aircraft were also returning from the raid at San Antonio de LOs Banos.

No mention is made regarding the difference between the FAR B-26s and the attacking CIA provided B-26s. The FAR aircraft had plexi glass noses while the CIA aircraft had metal noses this became an issue I the UN hearings when Cuba accused the US of staging the raid from outside Cuba countering the US position that the planes were defecting from the Cuban air force.

There is another point that requires attention and possible correction. The article mentions the destruction by FAR aircraft of an M-4 Sherman tank. This is highly unlikely for the invaders were equipped with light tanks not M-4s. I think the invaders had M-41tanks.

There is no mention of the Alabama Air National Guard pilot and crew members that flew combat missions over the battle. Four died as a result.

This week two important participants in the Bay of Pigs invasion died. Grayston Lynch known as Gray to the brigade members was a former US Army Captain who was a defacto leader of the brigade. Gray fought with distinction in both WWII and Korea he was wounded during both wars. The other member that just died was Former Cubana Air Line pilot Gustavo Ponzoa who flew a B-26 during the invasion and was one of the pilot that took part in Flight Lobo on April 18 196 inflicting heavy casualties on ground forces counter attacking against the exile invader,

As a child I spent some days at Camp Columbia because my father imported dairy cows from Wisconsin to Cuba. They were shipped to Florida by rail and then flown to Cuba in C-46 Curtiss Wright Commandos of Aero Vias Q. While at the field I saw many of the FAEC- Fuerza Aerea Ejercito de Cuba aircraft but I was too young to identify them. I did fill in what they were later. F-47 I remember clearly for I walked just a few feet away from them while they were being ammunition with cranks into the wing guns. Don’t remember seeing T-33s at the base but did see them and hear them flying over the city and particularly at the beach, not sure but there were what sounded like sonic booms. Probably shallow diving them to create the boom. Remember C-47s and other aircraft I couldn’t identify. I was about 9 years old and fell in love with aviation. Particularly those WWII warbirds.

it would be interesting to get some clear info on the C.46 and C54 used as logistics and para troops the story is fascinating some came from Air America from as far as Taiwan, there are some photos, but all poor quality

C-46 transports that had been operated by Air America in Asia were used to supply anti Castro rebels in the Escambray mountains of Central Cuba in 1960-61. Castro was ab le to put the rebellion down though some held out into approximately 1965. I knew one of the paratroopers that landed near the Australia Sugar mill he and his fellow troopers were transported in C-54s.

Hello, since the t-33 are trainers, how is it they were armed with guns? Was that a special modification, or was it uncomplicated…and does anyone know when they became armed? By Batista?

The Lockheed T-33 is able -by design- to have two or four machineguns installed on the nose, plus three rocket rails and one bomb rack under each wing.

As far as I know the T-33 s were not armed by Batista and F-80s were to be supplied to FAEC but Batista severely violated the terms of the MAP with the US thus the F-80s were never supplied.

To Rolando Figueroa.

Your father was a coward pure and simple. It’s hard to hear because he was your dad but it’s the truth no matter how he tried to spin it.

He was asked by Raul Castro to go up and take a look at what was going on. Once he realized that it was just an amphibious attack he made the conscious decision to turn back and not fire on the poor souls coming in on zodiacs. My father attended Fork Union Military Academy in Virginia and knew half of his classmates where probably on those zodiac’s. My father wasn’t a communist and left the air force the moment he stepped foot on ground.

Muy interesante este artículo pero está incompleto.

En los miembros del personal de tierra encargados de trabajar en los Sea Fury no aparece el nombre de mi padre Tirso Campanioni, era el jefe de línea de vuelos , fue el encargado de ensamblar los últimos Sea Fury que se recibieron (5) realizó varias innovaciones para mantener estos aviones de alta

Pueden consultar mi sitio

Nuestra Fuerza Aérea su Historia , aparecen varios artículos referentes a su trabajo realizado durante toda su vida en la Fuerza Aérea .