In early 1982, Lt. Roberto Címbaro was on his third year of assignment to the III Brigada Aérea (3rd. Air Brigade) of the Argentine Air Force, flying FMA IA-58A Pucará ground attack planes out of the Reconquista Air Base. However, his routine practice sorties came to an unsuspected end when on April 1 he and four other officers in his squadron, namely Captain Roberto Vila and Lieutenants Miguel Giménez and Héctor Furios, were ordered to head South immediately, to Tandil, the home of the IV Brigada Aérea (4th Air Brigade.) Since the high command didn’t explain what was the purpose of such impromptu deployment, Címbaro and his comrades assumed that it all was part of a training mission.

The four-plane flight landed at Tandil shortly before sunset that same day, and the pilots set to prepare themselves to spend the night there. However, their Pucarás were refueled within minutes of their arrival, and then were ordered to continue down South, to Río Gallegos, where they landed during the wee hours of April 2. Cimbaro recalls: “It called my attention the movement we saw, but we were so tired that we went to sleep. It was about 4 or 5 in the morning. I woke up five hours later and learned what had happened…”

What had happened was that their planes had been taken to Puerto Argentino (Port Stanley) by other pilots. The next day, Címbaro made the “crossing” to the islands.

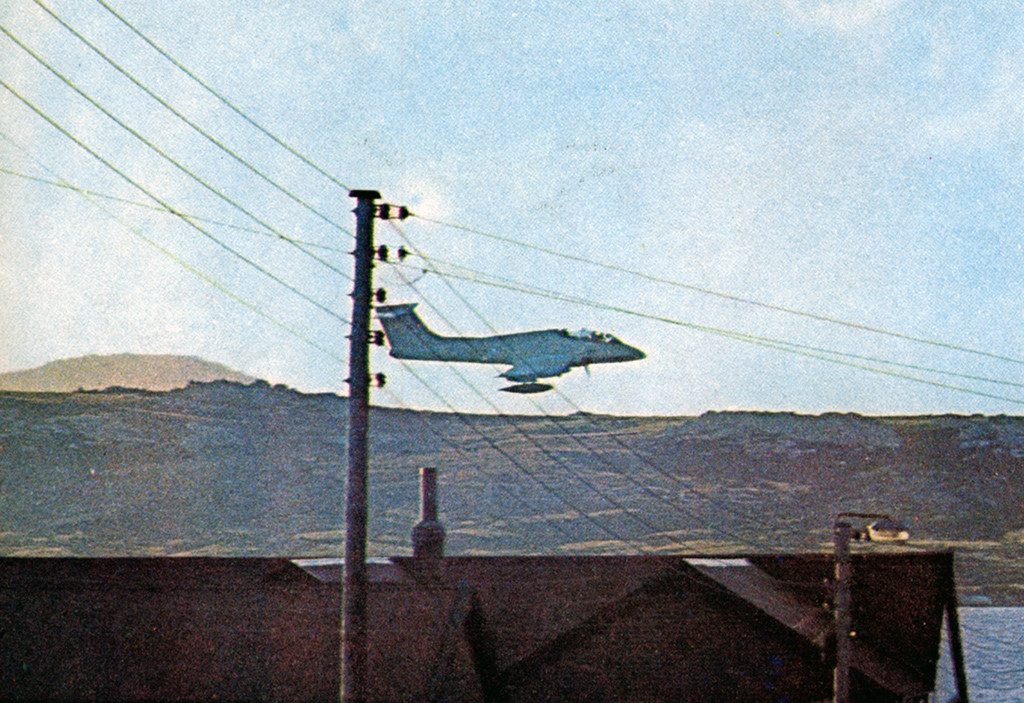

During the first few days after their arrival, Címbaro and the other Pucará pilots looked for a place to set up their equipment but ended up using the hangar of the Falkland Islands Company. The familiarization flights began shortly after, but the type of combat missions they were going to fly required that the Pucarás would be based in forward airfields. Thus, by mid-April, the pilots began looking for suitable grass strips across the island. Additionally, this was a safety measure in case the runway at BAM (Base Aérea Militar – Military Air Base) Malvinas was bombed.

Due to the roughness of the terrain, one of the few options for a forward operating base was a short strip located in Goose Green, which was named BAM Cóndor, and the pilots moved there by the end of the month. “The area where the airfield was established was squared and we used the diagonals for taking off and land. There weren’t any facilities whatsoever. The surface was so irregular that some planes broke their nose wheels during take off. The soil was very soft and with the airplane lightly loaded, we had no problems; however, fully loaded with fuel and weapons it turned out to be very difficult to even taxi the Pucará. One time, at Borbón / Pebble Island, while trying to leave the runway so the other planes could land, I rolled right into a soft spot and my nose wheel got stuck and broke” remembers Címbaro. Then he adds: “On May 1, we were sleeping on a barrack located about 500 mt from the runway when we were ordered to scramble. As soon as we reached the planes, the commander assigned us the order of departure and told us to get the Pucarás out of the airfield as soon as possible. The British had bombed BAM Malvinas and it all indicated that we were next. The ground crews were assisting the pilots to get the first two planes fired-up when one of them failed. Thus, Lt. Alcides Russo and I were ordered to take their place and depart the airfield as quick as we could. Behind us, I think, it was Lt. Grunnert who, while taxiing out, got his nose wheel stuck in the mud, further delaying the departure for the rest of the squadron. We took off and left the area at medium altitude, hoping that the rest would catch up with us. A couple of minutes later, Russo broke radio silence and said ‘Look to the left…’ As I turned my head, I saw two plumes of smoke rising from the airfield. The Sea Harriers had just attacked. To this day, I don’t know why they didn’t see us. In any case, we headed to Borbón / Pebble Island where we stayed for the rest of the day, while more planes arrived from BAM Cóndor. During the evening, the returning crews told us about the disaster caused by the bombing which killed several mechanics and one of the Pucará pilots named Daniel Jukic.”

From then on, the Pucarás were periodically rotated between the forward air bases of Borbón / Pebble Island, BAM Cóndor and BAM Malvinas, depending on the type of missions they were required to fly. During one of those rotations, Címbaro experienced an assault by the British Special Air Service -SAS- “We were sleeping in our tents close to the runway when we were awakened by huge explosions. The next thing we saw was our planes going up in flames. We tried to run towards the Pucarás that remained standing, but the SAS troops fired at us with their machine guns, so we had to take cover immediately. Then the British began detonating two strips of explosives they had set up along the runway but only one worked. Minutes later, the British decided to end the attack and withdrew, leaving a lot of combat gear behind. Since the airfield had been disabled, a Chinook helicopter was sent to evacuate us to BAM Malvinas.”

A few days after the landing of the British force in the islands, Címbaro was required to fly a search mission, because there were reports that a Sea Harrier had crashed near the coast and the pilot had ejected. The objective was to attack the helicopters that would be sent to rescue the downed pilot. Címbaro took off and headed for the area of interest, but within minutes, BAM Malvinas ordered him to return because a couple of Sea Harriers were approaching him. “I managed to return to the safe area around Puerto Argentino in no time, and kept flying over the town at low altitude until the Sea Harriers decided to abort their mission. When they left, I finally landed” Címbaro recalls.

Days later, Címbaro flew another hair-raising sortie: “I think it was with Néstor Brest. Anyway, one morning we were ordered to patrol all over the islands while looking for equipment left behind by the SAS troops. We were at it when a forward air traffic controller informed us that two Sea Harriers were coming at us. Strangely, the jets didn’t make their letdown and stayed circling at 15,000 ft. We immediately departed the area and headed for BAM Malvinas where we intended to land. However, the tower denied us authorization stating that if we landed, the Sea Harriers would bomb the airfield. We therefore, kept flying low over Puerto Argentino, waiting for them to leave. It took almost an hour for the Sea Harriers to run low on fuel, but before heading back to their base, they dropped their bombs near the airport. Then, we were allowed to land.”

After the arrival of the British troops in the islands, it became difficult to track their movements, especially for the Argentine pilots assigned to ground attack missions. Címbaro recalls that after May 28, they began taking more care when attacking ground positions, because they weren’t able to tell who was friend or foe. They also learned to refrain from returning for a second bombing or strafing run: “We kept our finger on the trigger; if we saw something, we fired.”

First Strike

“On May 28 I flew two missions,” says Címbaro. “BAM Malvinas was in full-alert and no vehicles were allowed near it. Therefore, the crew that was assigned to relieve us wasn’t able to make it on time. Thus, we were ordered to take off despite having been on duty during the night. Vila was the flight leader, I was number two and Argañaráz was number three. It was Argañaráz’s first combat mission on the islands, since he had arrived just a couple of days earlier. After take off, we were guided to our target, which was a group of houses where British troops had set up an artillery position. The leader fired off his rockets first, I did it next, and then it was Argañaráz’s turn. However, when he was coming out of the attack run, he saw a missile coming up from one of the houses and alerted me over the radio. I didn’t understand what he was saying but I managed to catch a glimpse of a tiny red dot speeding above me. Somehow, the missile had failed to get a lock on my plane, perhaps because it had been fired from the front. Less than two seconds later, another missile exploded under Argañaráz’s plane and the shockwave inverted it. He thought about ejecting, but being so low and upside down, he decided to stay with the plane and continued the roll just to see if the flight controls responded. Fortunately, the plane was still flyable, so he got out of the area and began looking for us. When he failed to find us, he decided to return to BAM Malvinas on his own. As for the target, we didn’t see what damage our rockets caused, but we destroyed the houses for sure. This attack began around 9 AM. I returned for a second attack an hour later. Then, at 11 AM I took off for another mission. The weather was horrible.”

Against Helicopters

Címbaro volunteered to go on a second mission that same day because the rest of the available Pucará pilots were still considered “green”, since most of them had flown only once since their arrival. His intention was to teach them the lessons learned so far. Thus, it was decided that the first pupil to go with him would Lt. Giménez. Their mission would be to look for targets of opportunity near BAM Cóndor.

About this mission, Címbaro recalls: “We arrived over BAM Cóndor after 20 minutes and as we were trying to contact them over the radio, we spotted two helicopters coming at us. Giménez asked if I had seen them and I replied that I had them in sight. Then Giménez asked the forward air controller if the helos were ours (to me they seemed to be Bell 212s), and he replied that they were British. Less than a second later, the helicopter crews saw us and broke formation, heading in opposite directions at full speed; I went after the one on the right while Giménez went for the other.”

“As I was going after my target, I saw Giménez firing his rockets. Seconds later he began yelling ‘I shot it down! I shot it down!’ and that was the last I heard from him. Meanwhile, I was having difficulties in centering the helicopter in my sight, as it changed course abruptly every time I was about to lock it. Then, the helo got very close to the ground, and I decided to fire all the rockets I was carrying. As some of the rockets began exploding around the helicopter, I saw that one of its blades hit the ground, and then it crashed. Coming out of the attack run, I realized that I was heading in the wrong direction (towards San Carlos), so I turned around and passed over the crashed helicopter again. In no time at all, the British survivors fired at me with all they had, hitting my plane more than fifty times.”

During the flight back to BAM Malvinas, Címbaro tried repeatedly to contact Giménez. At some point the young pilot replied that he was “climbing into the clouds”, to what Címbaro replied “I’m below you, in visual, under the clouds.” Still with Giménez out of sight, Címbaro realized that they were already flying over the ocean so he instructed him to turn left and head back to BAM Malvinas, but this time there was no answer. Then, Címbaro contacted the ground radar operator and asked him to locate Giménez. The operator replied that he had a small return in his screen, but within seconds, he had lost it. Címbaro tells what happened next: “As soon as I landed, the ground crews asked me about what had happened with Giménez. I replied: Calm down! We got separated during the attack and while flying back here he got into the clouds, but he is coming, I’m sure.” Sadly, it seems that Giménez miscalculated and began his letdown thinking that he was over the sea. Minutes later his plane slammed against Blue Mountain, the highest hill on the island.

As for the British helicopters, both were heading for the frontline to pick up wounded troops. The Westland AH.1 Scout that Giménez shot down with his rockets was XT629; the pilot, Sgt. Richard Nunn, was killed in the crash while his gunner, Bill Belcher, lost his left leg. According to Belcher’s account, Giménez’s Pucará attacked them first with machine-gun fire and then with its rockets. On the other hand, the helicopter shot down by Címbaro was also a Scout, serialled XP902. Címbaro’s after-mission report states that he made three passes over the helicopter, but in the first two he didn’t fire, because his cannons jammed. During the third pass, he decided to salvo his rockets.

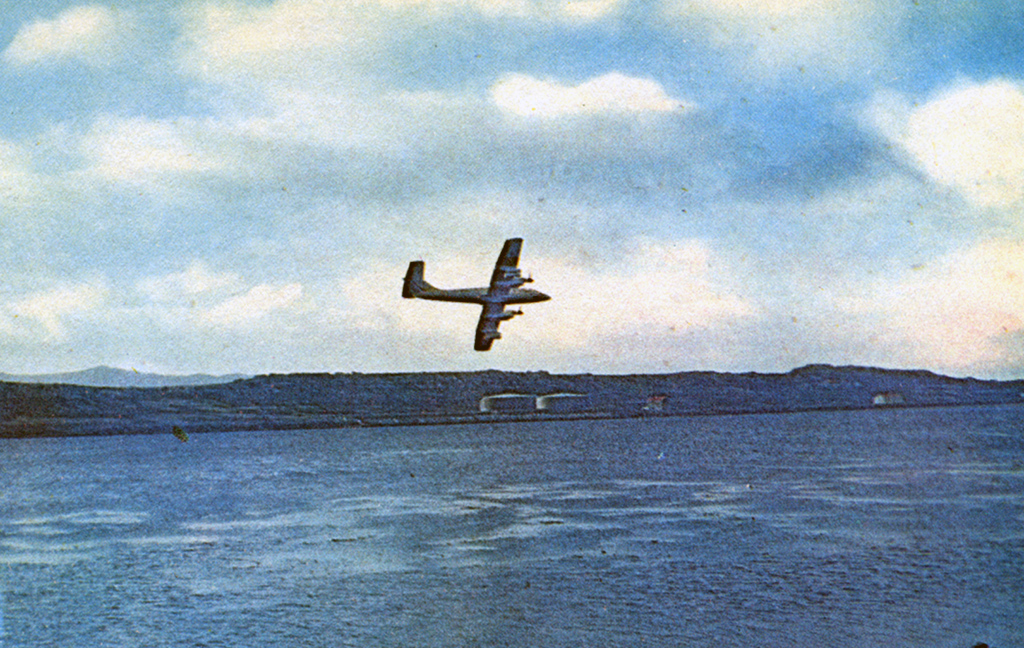

On May 29, Címbaro was ordered to return to the mainland. He left the islands that same day on a Lockheed C-130 transport bound for Reconquista. From there, he went to his home in Resistencia for some rest. Days later, he was assigned to BAM Santa Cruz in Río Gallegos where he was included in a squadron that was about to fly what could be considered a suicide mission: The Pucarás would be loaded with Napalm canisters and enough fuel to reach the Two Sisters area, where a major battle was taking place. After dropping the Napalm, the pilots would try to return to the mainland, something that was almost impossible. Fortunately, the mission, scheduled for June 12, was cancelled. “It would have been the first time that I would be sitting in my plane’s cockpit, shaking of fear” says the experienced pilot.

About the Pucará

After the war, the Fábrica Militar de Aviones, the maker of the rugged Pucará, continued delivering planes in order to replace those that were lost before 1990. By 2012 at least 30 IA-58s were assigned to the Grupo 3 de Ataque (3rd Attack Group) of the III Brigada Aérea at Reconquista. However, less than 10 were considered operational. Since 2009, a modernization program was started and it included the installation of new communications equipment. A second phase would include the modernization of the navigation suit with the installation of INS, HUD, and GPS equipment. Last, but not least, a third stage considers the replacement of the engines with a variant of the Pratt & Whitney PT-6 turbine. As for the armament, and despite that many weapons systems had been tested on the plane, it still carries the conventional ordnance comprised of rocket launchers and free-fall bombs, as well as its internal cannons. During the early 2000s, the planes took part on international exercises like Ceibo 2005 in Argentina and Cruzex III in Brazil. Surprisingly, besides close air support missions, the Pucarás have been flying in border control and anti-narcotics operations, especially over the Northern border where they have conducted successfully several interceptions, even though the pilots are not authorized to shoot down the drug-running planes.

The second Scout claimed as downed, actually survived to the war (XP902) and its cockpit is still visible. Perhaps the helicopter was forced to land, but surely it did not crash as claimed. https://www.airplane-pictures.net/registration.php?p=XP902

https://www.helis.com/database/cn/27645/

You are quite right. I was the Flight Commander and pilot of Scout 902 and having evaded Cimbaro’s initial solo attacks I survived further attacks by both Pucara after we lost Richard Nunn before gaining ground toward Camilla Creek House where ground troops engaged the enemy aircraft. I re-launched to recover Sgt Belcher who was badly injured and flew him to Ajax Bay before returning to the battle. I have seen various reports over the years of Cimbaro’s claims of his actions that day and it is disappointing when the facts are wrong. It might explain why he refused to discuss the conflict with me when I tracked him down some 20 years ago. In post-action reports from Cimbaro himself I was flying a Sea King (!) or crashed when shot down by his rockets. Unlike Cimbaro who left the Falklands immediately after Goose Green, I remained with 3 Cdo Bde RM right through to the surrender of the enemy on June 14th. I think it is important even after almost 40 years to ensure history is recorded correctly.