It could just be a simple story of a pilot running his airplane out of gas and ditching in the blue Western Atlantic Ocean, bobbing around in the warm water awaiting a rescue that would never come. Or, it could be a harrowing tale wrapped up in the nefarious world of international intrigue, mercenaries and revolutionaries. Many of the facts surrounding this missing person case are rather dubious, are perhaps only innuendo, or should be just considered legend and lore. However, there is a healthy touch of veracity to the tale and it all may actually be true. In any case, what is certain is that on 20 November 1963, Frank E. Bass took off out of San Juan, Puerto Rico, in his compact little Colonial Skimmer amphibian airplane, for what should have been an easy flight up to a fuel stop in the Turks and Caicos Islands. He was never heard from again, and no trace of his airplane has ever found.

Frank Earl Bass was born on 31 March 1911, in Calhoun County, Arkansas, the son of Henry L. Bass and Maude Bass – nee Wise. Of his childhood years, little has come to light. His father did pass away in 1916, and his mother appeared to have moved at some point to Freer, Texas. Frank had at least one sibling – Raymond H. Bass, who later won a level of renown as a U.S. Navy submariner during World War Two. It should be noted that while the U.S. Federal Census records are a wealth of information, there is a certain opportunity for error. Not an error in the data it- self, although the data has occasionally been in wrong, but rather the opportunity for a researcher to apply the correct data to the wrong person. Amazingly, there are often several people with similar names, birthdays, living in the same place, etc., which could steer a researcher in the wrong direction, prompting them to follow the incorrect path. With that in mind -the 1930 Federal Census records for Houston City (sic), Harris County, Texas, lists a Frank E. Bass, 19 years old, born in Arkansas, and now resident as a prisoner in the county lockup. The name, age, birthplace, as well as the birthplace of both parents, all point to our Frank E. Bass. It can be reasonably, but not definitively, assumed that this is the correct Frank E. Bass, whatever his in- fraction may have been. That said, and adding a bit of confusion to the tale, there is another Frank Bass, also in the 1930 Federal Census for Houston City, listed as the son of one Maud (sic) Bass, both of whom are noted as being born in Texas. Regarding this Frank Bass, although his birthplace has varied, his mother’s name is close, and his age is correct, so this too could be the correct Frank Bass. It is not unheard of for a person, especially one who has no permanent home, to be record- ed twice in a particular Federal Census. For one Frank Bass, or the other Frank Bass, or both, this is a mystery.

One unique aspect of the 1940 Federal Census is that there is an entry on the form listing where someone lived five years earlier – in 1935. So, for this iteration of the Federal Census, there is a Frank Bass listed as living, in 1940, in the town of Springhill, Louisiana, while it is noted that in 1935, he had lived in Long Beach, California. He is also noted, which is corroborated by further documentation, that he is married to Lorraine Bass-nee Jarnagin. A 12 March 1938, newspaper announcement of the wedding -they were married on 3 March- noted that Miss Jarnagin was a native of Springhill, and that the couple planned to live in that place. The 1940 Federal Census records Bass’ occupation as an “electrician” at a paper mill, which seems correct in light of later records. Regarding Bass’ married life, later references indicate he was married upwards of five times, but only the records associated with he and Lorraine have come to light. A later newspaper article noted that Bass was getting ready to be married for the sixth time, to a Puerto Rican lady named Maria Amparo Vargas. Another record that is extant is a draft registration card that was filled out in October 1940, by Frank Earl Bass, on which he listed his address as the town of Orange Park, Florida, and that he was working for an electrical firm. He also notes on the card that the name of the person who will “always know your address” as his uncle – Guy A. Wise. No mention of Lorraine. Although Frank Bass duly registered for the draft, no records found to date indicate that he was ever actually drafted, nor whether he was ever in the military.

That’s about all that is currently known for the life and times of Frank E. Bass, up until the late 1940s, when he is found to be a reasonably well-established businessman an area known as Cinco Bayou, a small town near Fort Walton, in the western panhandle of Florida. (This was in an era before the town was called Fort Walton Beach, the “Beach” being added in June 1953.) Of this early portion of his life one must exercise a modicum of caution as the records are scant, and no close relatives have been found. And, as mentioned, there was more than one “Frank Bass,” of about the same age, living at the time, so caution should be exercised when making claims. Perhaps one day a blood relation of his will be found, someone who can rattle off the tale of Bass’ life from start to finish. Until then, this is what is known.

The basic outline for the rest of Frank Bass’ story is based on a series of articles that appeared in November 1973, in the Pensacola News Journal (PNJ) newspaper. Written by local reporter Bill Tennis (1929-2017) on the tenth anniversary of Frank Bass’ disappearance, it is a rousing tale that often reads like a paperback adventure novel, even delving into that infamous region known as the Bermuda Triangle. While it is an interesting read, the article tends to leave many questions unanswered. Mr. Tennis does interview several people, but he often does not press for specific dates, so it is kind of hard to establish a timeline. This is not a dig on Mr. Tennis, as many of these questions he looked into may not have been answerable back then, and in fact may never be answerable to this day. So, with Mr. Tennis’ article as an outline, supplemented with various additional newspapers, documents and references that have been dug up today, this is what is known of the rest of Frank Bass’ life.

Sometime in the mid-1940s, Frank Bass come to the Fort Walton area. As noted by Mr. Tennis, he was employed at the “Climatic Hangar at Eglin AFB [Air Force Base],” which refers to what is today called to the McKinley Climatic Hangar. Opened in May 1947, at what was then called Eglin Field, this huge hangar is used to test aircraft under simulated extreme weather conditions. In June 1971, the complex, which is still operation today, was named for Lieutenant Colonel Ashely McKinley under whose supervision the original facility was built. So, sometime on or after May 1947, Bass was living in the area. One of the first solid references to Frank Bass appeared in the 16 November 1947, issue of the PNJ, noting that he attended a meeting, held in Panama City, Florida, of the newly founded West Florida Aviation and Trade Association. This group was formed to standardize airport policies and in general to promote local aviation activities.

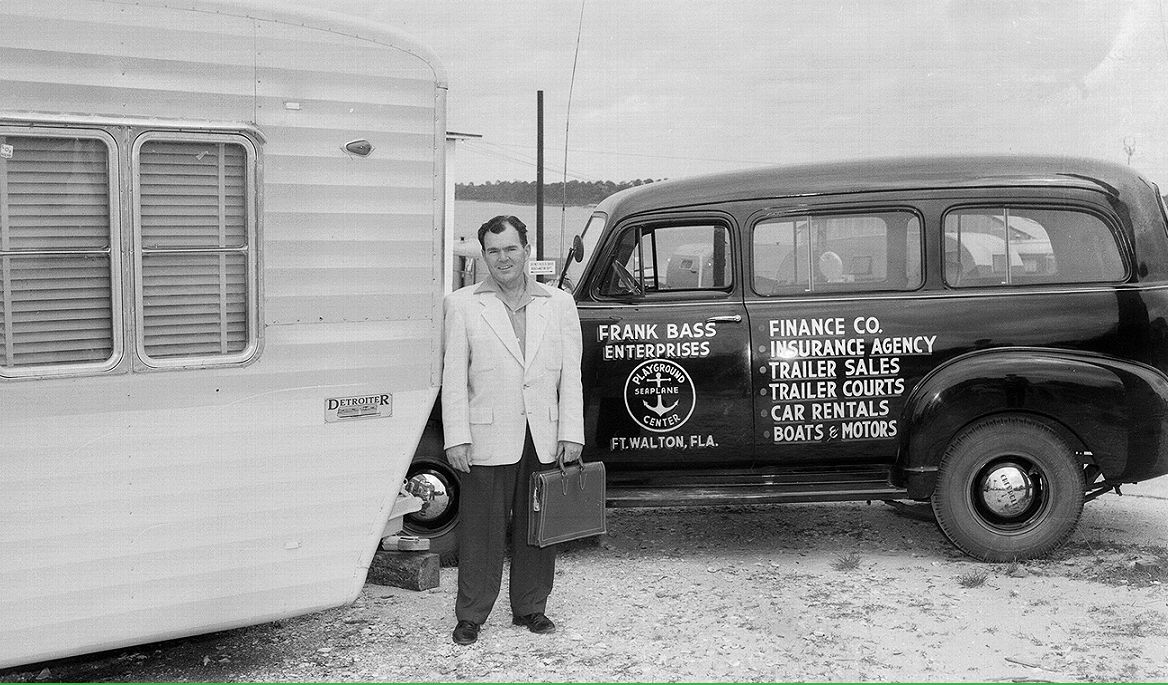

The next bit of data appeared as a classified advertisement in the 17 September 1949 issue of the PNJ, offering “House Trailers for Sale” by Frank E. Bass, located at the Playground Seaplane Center, Fort Walton, Florida. As Mr. Tennis records, around this time Bass was beginning to develop a myriad of business interests, including the buying and selling of trailer homes, and the establishment of trailer home parks in Fort Walton – the Frank Bass Trailer Park, and the Eglin Heights Trailer Park, to name two such properties. According to the story, Bass started off with a stake of $1,000, went over to Biloxi, Mississippi, and bought three trailers, which he towed back to Fort Walton, and from there his business just grew. The exact date he started this operation is not certain, suffice it to say it was in the last half of the 1940s. Bass’ business interests were multifaceted and in addition to trailer homes, he also started a rental car agency, owned a marina, dealt in real estate, opened an electronics store, and sold insurance.

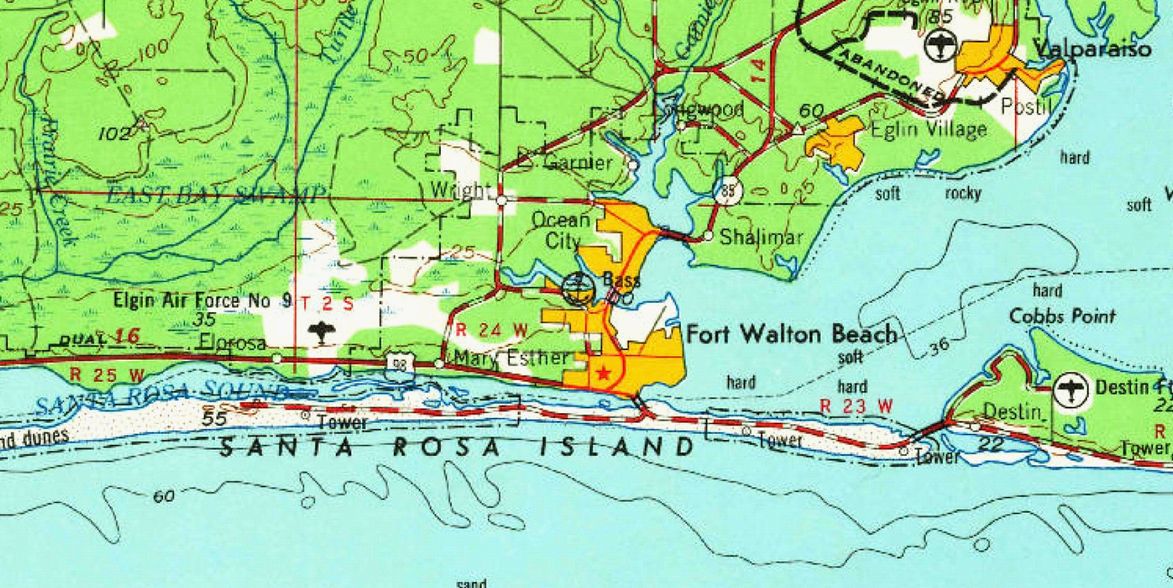

As a bit more confirmation that this is the correct man, the 1950 Federal Census for Okaloosa Country, Florida, which includes the Fort Walton area, has a listing for one Frank E. Bass, a divorced man of 39 years, noting that he was born in Arkansas, and is currently a manager of his own business in the trailer sales industry. No other family members are listed. There is a handwritten note on the bottom of this particular Census record form that reads: “Dwelling 251 [which is Bass’] to 259 in Cinco.” In the case, “Cinco” is a reference to an area called Cinco Bayou, located appropriately enough, on the banks of the Cinco Bayou, which was earlier called the Five Mile Bayou. On 3 July 1950, the people living in the Cinco Bayou all got together and incorporated a village under the same name. Bass’ Marina and his Playground Seaplane Center were located in this area, on the banks of the Cinco Bayou. To this day, Cinco Bayou is still an independent town, almost completely surround by Fort Walton Beach.

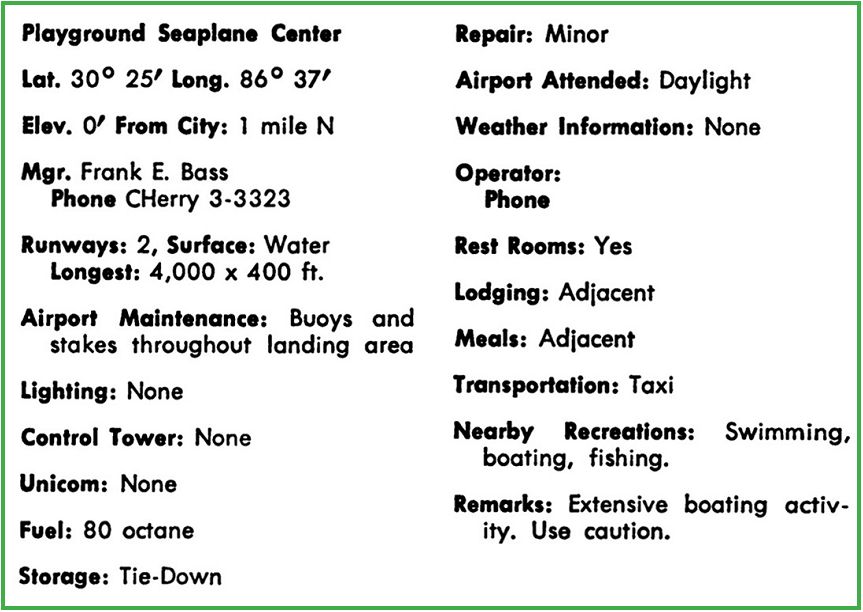

The wording of the above-mentioned newspaper advertisement indicates that by the fall of 1949, Bass’ had already established his own seaplane base the Playground Seaplane Center. As mentioned, his seaplane base was situated, co-located with his marina, in Cinco Bayou, at the southern end of the Cinco Bayou Bridge. There he also opened the Bass Flying Service and Flying School. The seaplane base soon appeared in various Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA – later after 1958, the Federal Aviation Administration – FAA) airport directories and aeronautical charts. Regarding Frank Bass himself, it is uncertain when and where he took his flight training. Notwithstanding, he apparently advanced to the rating of instructor pilot.

As a side note: After the end of World War Two, in an effort to entice people to come and vacation in the Fort Walton area, local promoters christened the area “Playground,” with all its imagery of carefree, sunny beaches.

The decade of the 1950s, saw Frank Bass as a relatively active member of the local business community, as well as a supporter of diverse social and charitable efforts. For example, in May 1951, he and his company were recognized as a supporter of the Armed Force Day activities at Eglin AFB. In March 1952, Bass, who had served as a director, was elected the president of the Playground Chamber of Commerce, and he also led the Cinco Bayou Business Men’s Association. He was the leader of groups ranging from the Playground Outboard Motorboat Club, to a delegation of locals campaigning for a new county hospital to be located in the Fort Walton area, vice farther north up in the town of Crestview. He was also a financial supporter of the county sheriff department’s Junior Posse, a youth group fostering “good citizenship and respect for law and order.” Offering his aviation expertise, Bass was an officer in the Florida Wing of the local Civil Air Patrol (CAP) squadron, later providing, at his own expense, a mobile two-way radio set to be used in communications between the CAP and the Air Force in search and rescue operations. Speaking of flying, on at least three occasions, Bass flew his own airplane in support of the county sheriff who was in pursuit of escaped criminals. One report in March 1961, notes that Bass, on at least this occasion, had been officially deputized by Okaloosa County Sheriff Ray Wilson, and was given arrest authority. Also, in late 1962, when the county officials balked at establishing the post for a juvenile counselor to help wayward youth, Bass offered to front the first several months of pay for the position. The juvenile counselor position was made permanent in January 1963. Diverse in his interests, Bass was also an avid square dancer, and even built a special barn to hold dances.

According to Mr. Tennis, sometime in the late 1950s, Frank Bass began to take an interest in the events that were unfolding on the Caribbean Island of Cuba. Like almost everyone in the U.S., he appears to have been a rather ardent anticommunist, a fervor that Bass would soon act upon. According to Art Drenious, a Fort Walton Beach real estate man, when: “Bass felt in sympathy with a cause, he went into it wholeheartedly. He was not only guided by reason and logic, but also greatly by his emotions.”

To briefly set the stage of this era, on 1 January 1959, Fidel Castro had chased the long ruling dictator Fulgencio Batista off of the island of Cuba, and soon had deposed the provisional president Manuel Urrutia, to become the undisputed head of the Cuban government. By early 1960, Castro was aligning himself with the Soviet Union, while simultaneously cutting most political and commercial ties with the United States. Of course, the failed Bay of Pigs invasion (April 1961) and the Cuban Missile Crisis (October 1962) did nothing to foster congenial relations between Cuba and the United States. There is one extant immigration passenger list – dated 21 March 1956 – that notes that one “Frank E Bass, age 44, born in Arkansas,” arrived at the port of Key West aboard the vessel SS City of Havana, which had departed the same day from the port of Havana, Cuba. Unfortunately, the form does not list the reason for his visit, so Bass’ actual interest in Cuba at the time is not really clear. Was he just a tourist, or perhaps something else?

Meanwhile, in the Dominican Republic political turmoil was the order of the day. On 30 May 1961, Dominican Presidente Rafael Trujillo was assassinated, ending an over 30-year regime of bloody terror. Although Trujillo did not always carry the title of presidente, nor sit in the office of the presidente, he continuously held firm domination over the country. Relations between the U.S. officials and Trujillo were strained, at best, but at least he was not a communist, so the U.S. tended to give him sway. After the assassination, various sons and brothers of the dead dictator quickly began scheming for control of the county, but in the end, they were all forcibly shooed out of the country, but not before looting the Dominican treasury. Still, many loyal Trujillos lurked in the background, and there began a prolonged period of various factions jockeying for control of the country. Quite amazingly, what was considered by many observers as a relatively honest election process, on 20 December 1962, a man named Juan Bosch was democratically elected president, a first for the country. Bosch’s took office on 26 February 1963, but his term in office did not last long, as on 25 September 1963, he was deposed in a military coup d’état, after which he fled to Puerto Rico. Although large groups of supporters demanded the restoration of Bosch to his elected office, he remained in exile in Puerto Rico for several years.

The second paragraph of the first installment of Mr. Tennis’ series of newspaper articles in the PNJ dramatically describes Bass’ life in the couple of years just prior to his disappearance. Mr. Tennis notes that Bass was a: “Soldier of fortune, experienced pilot, former president of the chamber of commerce, hard headed and tight-fisted, but sometimes a generous to a fault businessman.” Mr. Tennis continues: “Bass made guerrilla flights into Communist Cuba, was jailed in the Dominican Republic for flying in an ex-Trujillo general, and then disappeared in the notorious Bermuda Triangle.” Although it should be acknowledged that Mr. Tennis had probably interviewed dozens of people for his exposé, many of which he noted by name, in other cases he does not list the sources for many of the above listed claims, nor does he expound in any detail on several of these events. For example, the fact that “Bass made guerrilla flights into Communist Cuba” could use a bit more elaboration, e.g. how many of these flights did Bass log, who or what was he carrying, what were to points of departure and arrival. All questions that needed to be answered. Perhaps in Mr. Tennis’ belongings – he passed away in 2017 – is a well-worn reporter’s notebook that mentions the sources he used. And, perhaps in some dusty box in the back of a closet somewhere, there is Bass’ pilot logbook that lists each and every flight.

Not naming the source, Mr. Tennis recorded that: “Bass had been caught up in the anti-Castro fever that swept Florida after the Communist takeover. He had offered his two planes to the anti-Castro forces and had gone to South Florida to carry out those plans.” Again, quite maddeningly, who these people and what these plans were are not expounded upon. Rumors floating around Fort Walton Beach had it that Bass was working for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which Bass himself apparently confirmed through conversations with close friends. Art Drenious told Mr. Tennis that Bass had offered his services to anyone working to free Cuba. Again, of these flights little is known. Business associate Randy Counsman recalled that Bass told him of one flight were he landed on the coast of Cuba to pick up a man, whereupon he was fired bombed and barely escaped. Additionally, Bass flew at least one flight into the Dominican Republic, a country that after the assassination of Rafael Trujillo, many Americans saw as teetering back and forth between American-backed capitalism and Cuban/Soviet Union-backed communism. On this one flight Bass may have in a small way been helping to depose the current Dominican president.

At least two of Bass’ flights in the Caribbean islands are reasonably well documented. One occurred in July of 1963, a flight to the Dominican Republic, a forced landing, and subsequent arrest endured by Bass, that was chronicled in Mr. Tennis’ PNJ articles, as well as in contemporary articles in the Spanish language newspapers El Caribe (Santo Domingo) and El Mundo (Puerto Rico). No official documentation, i.e. governmental records, of Bass’ exploits during this time have been found. All these articles present a rousing, if a bit confusing and often contradictory, story. Bass’ other flight that is known, in November of 1963, was his last.

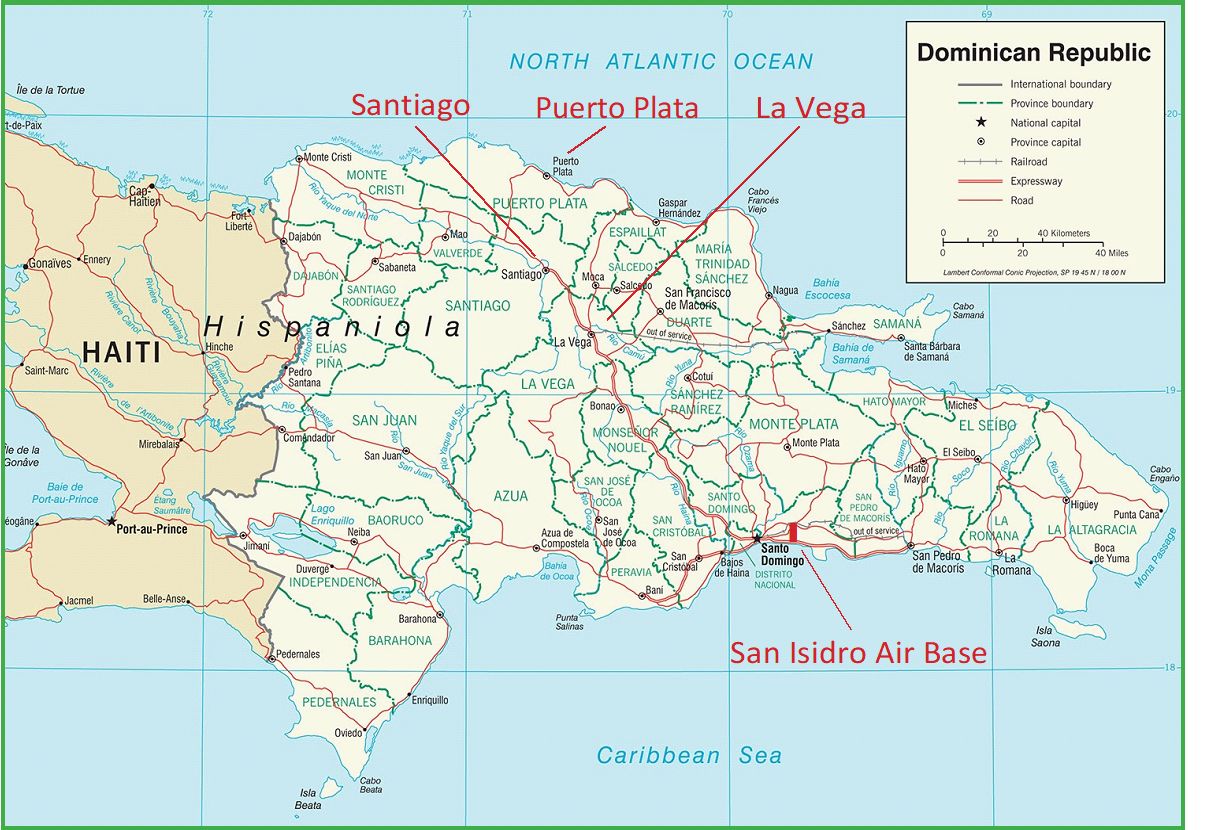

The origin point of the July 1963, trip is not certain, perhaps he started out from his home base in Cinco Bayou. The final leg of the flight, before Bass was arrested, could have originated from either the island of South Caicos, in the Turks and Caicos Islands, or from the Isla Grande Airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico. His destination, was also not totally certain, but it was someplace in the Dominican Republic. The aircraft he was flying was probably his Colonial C-2 Skimmer, a small, single-engine, amphibian. Reports vary, it was either engine troubles, or it was low fuel, as to what forced Bass to land where he did in the Dominican Republic. What makes either reason a bit suspicious was that Bass reportedly had a passenger on board, one Señor or ex-General – Pedro Rafael Rodriguez Echavarria, a former Trujillista Air Force General and Chief of the Air Force. So, perhaps Bass’ reason for landing in the Dominican Republic was neither engine problems, nor low fuel, but the covert return of an exiled general.

Apparently, General Echavarria’s earlier allegiance had turned against Trujillo, and after the dictator’s assassination, Echavarria actually was part of a faction that thwarted the attempted return to the country of two of Trujillo’s brothers. However, Echavarria, a former fighter pilot who had trained in the U.S., soon turned against Trujillo’s handpicked successor, one Señor Joaquin Balaguer, earlier selected by the dictator to the office of vice president. On 22 November 1961, now Presidente Balaguer, believing in Echavarria’s allegiance, named him as the country’s Secretary of State for the Armed Forces. As often happens, public acceptance of highly placed officials in the Dominican Republic was fleeting. Presidente Balaguer’s precarious administration was to prematurely dwindle, with the presidente agreeing, due to pressure of the military, to step down before the end of February 1963, well before the end of his term, scheduled in August 1963. He was not to have that chance, as on 16 January, Echavarria, claiming he had unearthed a nefarious Communist plot in the making, precipitated a coup against Balaguer. Echavarria’s own joint civil/military junta was short- lived, lasting less than 48 hours, when several air force junior officers turned on him in a military counter-coup, and tossed the general in prison. On 7 March 1963, Echavarria was deported and, with U.S. assistance and with the appropriate U.S. visa, was flown out of the Dominican Republic to San Juan, Puerto Rico. Many Dominicans decried that the flight of Echavarria, along with the escape of former Presidente Balaguer, who was separately flown into San Juan, prevented them both from facing justice, and was the result of U.S. connivance. The attendant protests soon followed. As mentioned, Juan Bosch had taken over the office of president on 26 February 1963. Change happens rapidly in the world of Dominican politics.

The exact date and place of departure for Bass and Echavarria’s flight into the Dominican Republic is not clear. As to the date, a relatively firm date appeared in one of the articles in El Caribe that stated that the “North American pilot Frank Bass” landed at the El Pontón airport, in the village of La Vega, on 10 July 1963. Another clue as to a date is an article that also appeared in the El Caribe newspaper, on 24 July 1963, that chronicled Bass’ recently concluded nineteen-days of arrest, along with the impounding of his airplane, in the Dominican Republic. Thus, Bass would have departed from somewhere, apparently with Echavarria on board, sometime around the first or second week of July. In addition to the articles in El Caribe, there is another article that appeared in the 23 October 1963, issue of El Mundo written by Malén Rojas Daporta, and based on Daporta’s interviews with Bass. This article mentions that Bass returned to San Juan, Puerto Rico, after his Dominican captivity, on 28 July 1963, which would have put his departure date around the 9th of July. This article also has a photo of Bass sitting in the cockpit of his C-2 Skimmer, although when the image was take is not certain.

All of these articles, chronicling Bass’ arrival, detention and subsequent escape from the Dominican Re- public, are a bit contradictory in places, as well as vague in some aspects, and often raise more questions than answers, but it’s all there is to go on. So, with that said…

Whether or not Bass began this adventure from his home base in Cinco Bayou is not certain, but this can be reasonably assumed, although he did have a friend and business associate living on Andros Island, in the Bahamas, so it could have been from there. By most accounts, Bass’ story of his final flight leg into the Dominican Republic begins in the Turk and Caicos Islands, which at the time was a British Crown Colony, and under the direct control of the British Colonial Office. Bass said he received a permission certificate from the British consulate to depart from the island and fly to the Dominican Republic. This document has not been found. There is no mention made in any of the newspaper articles of a stop in Puerto Rico, which was presumably where he picked up Echavarria. To the British consul, Bass claimed to be a simple retired businessman who was on a exploratory flying tour of the Caribbean. The permission certificate issued by the British consulate had a mistake on it, being made out for a ship-borne ocean passage vice a flight in an airplane, and when Bass landed at El Pontón airport, in the Dominican Republic, local officials became suspicious when they discovered the mistake.

In one article in El Caribe, Bass is noted as claiming he was actually invited to the Dominican Republic by British governmental officials. Contrary to this claim, the First Secretary of the British Embassy, a Mr. S.F. Campbell, denies knowing Bass, or the issuing of any such invitation.

Regarding El Pontón airport at La Vega, aeronautical charts dating back up to the early 1970s show a small airstrip, with a 2,100-foot, probably grass, runway. It was located to the southeast of the village of La Vega, the village itself located in the center of the country between Santo Domingo and Santiago – also called Santiago de Los Caballeros. More modern aeronautical charts, dating from around 1990, no longer depict an airfield at La Vega, and indeed it appears that the town grew and eventually engulfed the field. There is a neighborhood in La Vega, roughly where the airport used to be, called El Pontón.

Still another version of the flight from the Turk and Caicos Islands, noted in El Caribe, has it that Bass said he first landed in Puerto Plata, on the north coast of the Dominican Republic, then took off again and was flying to the town of Santiago – presumably Santiago de Los Caballeros – which he was noted as his destination, when he encountered whatever problems that may have cropped up forcing him to land at La Vega. Oddly, if this assumption was true, Bass would have had to fly past Santiago to reach La Vega, so if Santiago was his original destination, why didn’t he just land there?

The reason Bass landed at El Pontón airport is fraught with confusion, and varies from source to source. One reason was that he was forced to land due to fuel exhaustion, which does not really make sense. His aircraft, a Colonial C-2 Skimmer, had a range of over 400 nautical miles (NM), while the direct route from the Turks and Caicos Island to La Vega is only around 150 NM. If he did stop in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where he would had to have refueled, the run from San Juan to La Vega is around 260 NM. So, unless Bass got really lost and flew way off course, the idea that he was running out of fuel and had to make an emergency landing at El Pontón is somewhat of a stretch. Another reported reason for landing at El Pontón was airplane problems, which is also a bit of a stretch in reasoning since, as will be expounded upon below, Bass flew his Skimmer at least one other time, before he flew it again, this time out of the country. Of course, as mentioned above, the real reason Bass landed at El Pontón in La Vegas may have had nothing to do with fuel or airplane problem, but was simply a drop off his passenger – General Echavarria.

Upon landing at El Pontón, Bass was detained by what he called the Civil Aviation Intelligence Service and by the Immigration Service, initially due to confusion over the erroneous paperwork issued by the British consul. Soon, however, Bass was accused of bringing Echavarria back in to the country. What eventually happened to Echavarria is not certain, but it is not beyond the imagination that perhaps in all the turmoil he simply faded into the background. Did Echavarria have a group of compatriots waiting to whisk him away, and leave Bass to his own fate? For three days, Bass was subject to intense interrogation, and then, of course, the military showed up, in the form of a particularly nasty officer who accused Bass of being: “a perfectly trained saboteur,” saying that the forged documents proved it. Regardless of this charge, or perhaps because of it, at some point Bass was required to ferry his airplane down to the San Isidro Air Base, a Dominican Air Force Base located on the eastern outskirts of Santo Domingo. There was no mention of a faulty engine that would have prevented this flight. There followed another intense interrogation session, this time by the Chief of the General Staff of the Dominican Air Force, one General Miguel Atila Luna, that lasted some five days. While there, Bass was not really incarcerated, as such, but was under some type of house arrest. He was a guest at the residence of Mr. Francis Whitney, the American consul, who Bass states was the only person who stepped in to help him.

Reports state that when it came time to discuss allowing Bass to fly back out of the Dominican Republic, General Luna expressed a great deal of concern, stating that the aircraft, which he claims was damaged upon its landing up in La Vega, was certainly not airworthy. He could not, he explained, in all good conscience authorize Bass’ departure due to the Skimmer being in “poor mechanical condition.” General Luna explained that it would not be proper and that he could not accept responsibility if anything untoward would happen to the airplane and its pilot [Bass]. “We, who have the plane here [at the San Isidro Air Base], know very well that it cannot take off, in view of the fact that several mechanical damages have been found on it, and if we allow it to leave it will put the pilot in danger,” General Luna explained. He does not, however, comment on the fact that the airplane was flown down to the San Isidro Air Base with no apparent problems. Later, after he was out of the Dominican Republic, Bass commented that he thought that General Luna’s concern for his well-being to be totally feigned, that the general had taken a liking to the Skimmer, and was just looking for a way to keep it for himself.

Still another Dominican official got in the mix, this time a certain Señor Juan Molinó, director general of the Office of Civil Aviation. Molinó was a hard man to pin down, claiming that officials from his office had not yet had a chance to inspect Bass’ airplane, when according to a U.S. Embassy official by the name of Serban Villilarescu, inspectors from Civil Aviation had done just that. And, found the Skimmer to be in perfect condition. Villilarescu noted that Bass had all the proper FAA airworthiness documents issued for the plane. However, he also noted that Bass lacked certain Dominican tourism documents, as well as what he described as a “regulatory flight card,” which could have caused problems.

After a total of nineteen days under what seemed to be a rather relaxed confinement, Bass made his escape. Assisted by a sympathetic official named Lieutenant Colonel Jorge Marte Hernández, who was head of the National Police, Bass was accompanied by Consul Whitney when he took off and flew back to Puerto Rico. This would lend a bit of credence to the idea that the Skimmer was in good shape. The article in El Mundo notes that Bass did not have authorization, by order of General Luna, to depart, but neither did he have an expressed prohibition on departing, so with Hernández’ help, and with Whitney on board, no one stopped them. From the Isla Grande Airport, Consul Whitney took a commercial flight back to the Dominican Republic, and faced no apparent repercussions for assisting Bass.

So, if Echavarria was on board Bass’ airplane in July of 1963, what was he doing there? Recall that Juan Bosch took his oath of office as presidente in February 1963. Bosch was a progressive reformer, some say an outright communist, and many of his programs were not particularly palatable to the more conservative former ruling class in the country, the landed gentry, as well as many in the military. And, of course, the fervent anti-communists up in the U.S. were not adverse to seeing him go, even turning a blind eye to the possibility of some old elements of the Trujillo regime reinstated, that is if it reestablished the bulwark against communism spreading throughout the Caribbean by people like Juan Bosch. Thus, as was often the way, Bosch was forcibly deposed in September 1963, by a military junta, before the end of his first year in office. One local radio station announced: “Castro communism has been crushed.” Now this is only a guess, but maybe Bass was flying in ex-General Echavarria to participate in this coup, after which Echavarria could perhaps look forward to assuming some high position in the new government. In the El Mundo article Bass was quoted as saying: “Everyone there knew that the coup [against Juan Bosch] was being prepared.”

Of course, the questions surrounding this whole episode are very numerous, indeed. Did Bass fly this trip out of his personal opposition to communism, or was he on someone’s payroll, or both? How did he and Echavarria come into contact, again through Bass’ own efforts, or by the machinations of some third party? Even a cursory examination of this period of the history of the Dominican Republic will show quite of bit of involvement by the United States, both overt actions promulgated by those in the Department of State, and clandestine actions carried out by various spooks in the U.S. intelligence services. Was Bass, a seemingly mild-mannered, unassuming Florida businessman, working for none, some, or all of these folks? And, whatever happened to General Echavarria?

There is a rather strange portion of an article about Bass that appears in the 24 October 1963, issue of El Caribe. Bass relates that after he left the Dominican Republic in late July 1963, he kept much of what happened to him a secret because he wanted to return to the country. According to the article: “Bass says that he would like to return to the Dominican Republic, since it is a very beautiful country where he would like to spend some vacation time.” Bass personally wrote to then President Juan Bosch asking him for an explanation of his detention, and for permission to return. No replies were forthcoming, and after Bosch had been deposed, none would ever be. Bass said: “Shortly after, when the coup was done, I understood that this was impossible.”

What Frank Bass did, and where he lived after he managed to leave his confinement in the Dominican Republic is pretty murky. One question was whether or not he flew back up to Cinco Bayou, or did he just bide his time in Puerto Rico. There is some validity in the latter assumption as Bass was known to have rented an apartment in the Rio Piedras section of San Juan, and was taking Spanish classes at a local college. The article by Bill Tennis, in the PNJ, records a few snippets of information that while not exactly definitive give an idea of Bass’ days before he disappeared. A friend of Bass’ by the name of Lloyd Bell, a Fort Walton Beach businessman who was now living on Andros Island, in the Bahamas, was supposed to go with Bass, as a copilot, on what would end up being Bass’ last flight. Apparently, Bell knew of Bass’ earlier planned clandestine flight in to the Dominican Republic, and advised him not to go. Bell said to Bass that if he got in trouble: “There was nothing we can do for you down there.”

The two were planning on flying from San Juan up to Andros Island, where Bell was going to buy Bass’ amphibious Skimmer. Bell was going to help Bass develop some property investments in the islands, noting that Bass had upwards of $100,000 in cash to help get the deal started. Bell also noted somewhat cryptically that Bass indicated that he really didn’t care was happened to him. Unfortunately, Bell does not expound on Bass’ sentiments, or mental state, at the time.

Bill Tennis did record one comment that leans toward the theory that after leaving the Dominican Republic he did fly at least once back up to Fort Walton Beach. A local lady by the name of Mrs. Wallace Price, who managed one of Bass’ trailer courts, stated that Bass told her: “He was scared of the Dominican Republic. They [General Luna?] liked his airplane, but they didn’t like him,” and that Bass recalled his experience there as a “nightmare.”

On the morning of the flight, Lloyd Bell had an odd feeling. He told Bill Tennis that: “It was like someone had poured a pitcher of cold water on me. I had a premonition; the plane was not going to make it. It was absolutely not going to make it.” Bell, and Maria Amparo Vargas, Bass’ fiancée, tried to talk Bass out of going, suggesting instead they just disassemble the Skimmer and send it north on a cargo ship. A local Civil Air Patrol pilot by the name of Lieutenant Colonel Albert Crumely also tried to talk Bass out of flying this trip. Bell noted that there was some discrepancy on the accuracy of the airspeed indicated, but nothing was proven. Local Fort Walton Beach man recalled to Mr. Tennis that: “The plane was in perfect flying shape.” However, other Fort Walton Beach men, including Randy Couseman and C. Walter Ruckel, told Mr. Tennis that Bass didn’t properly maintain the Skimmer, doing only enough to keep it flying. Who to believe?

Other than Bell’s weird premonition, it seems odd that so many people were concerned about Bass making this flight, after all Bass had on a number of occasions apparently made this same flight successfully in the past. What was so different now? In the end, Bell noted: “There was nothing I could do to make him change his mind.”

A few months after Bass had endured his enforced sojourn in the Dominican Republic, the headline in the 23 November 1963 issue of the El Mundo newspaper read: “Search For Two Little Planes Lost Near Puerto Rico,” followed by a brief article written by Señor Eddie Figueroa. One of those little planes was a Cessna 180 piloted by a man named Adadías Earvealito, who took off out of Miami, Florida with a final destination of Puerto Rico. He never arrived and was never found. The other little plane was a Colonial C-2 Skimmer – registered N283B – piloted by Frank Bass. At 8:28am, on 20 November 1963, Bass took off out of San Juan on the first leg of a trip, presumably just up to Andros Island, with his first fuel stop being the Turks and Caicos Islands. He too never arrived and he too was never found.

At 1:45pm, when the two aircraft were reported overdue, rescue aircraft out of Miami were launched to look for the Cessna, while assets based in Puerto Rico began the search for Bass. By the end of the week there were upwards of a dozen aircraft from the U.S. Coast Guard, Navy, Air Force and the Puerto Rican Air National Guard looking for Bass’ diminutive Skimmer. Civilian airline crews and merchant sailors were requested to keep a look out for any debris. To this day, nothing of Bass’ Skimmer, nor the Cessna for that matter, has ever been found. All told, some 20,000 square mile of ocean had been covered when the search was finally called off five days after Bass failed to show up on South Caicos Island.

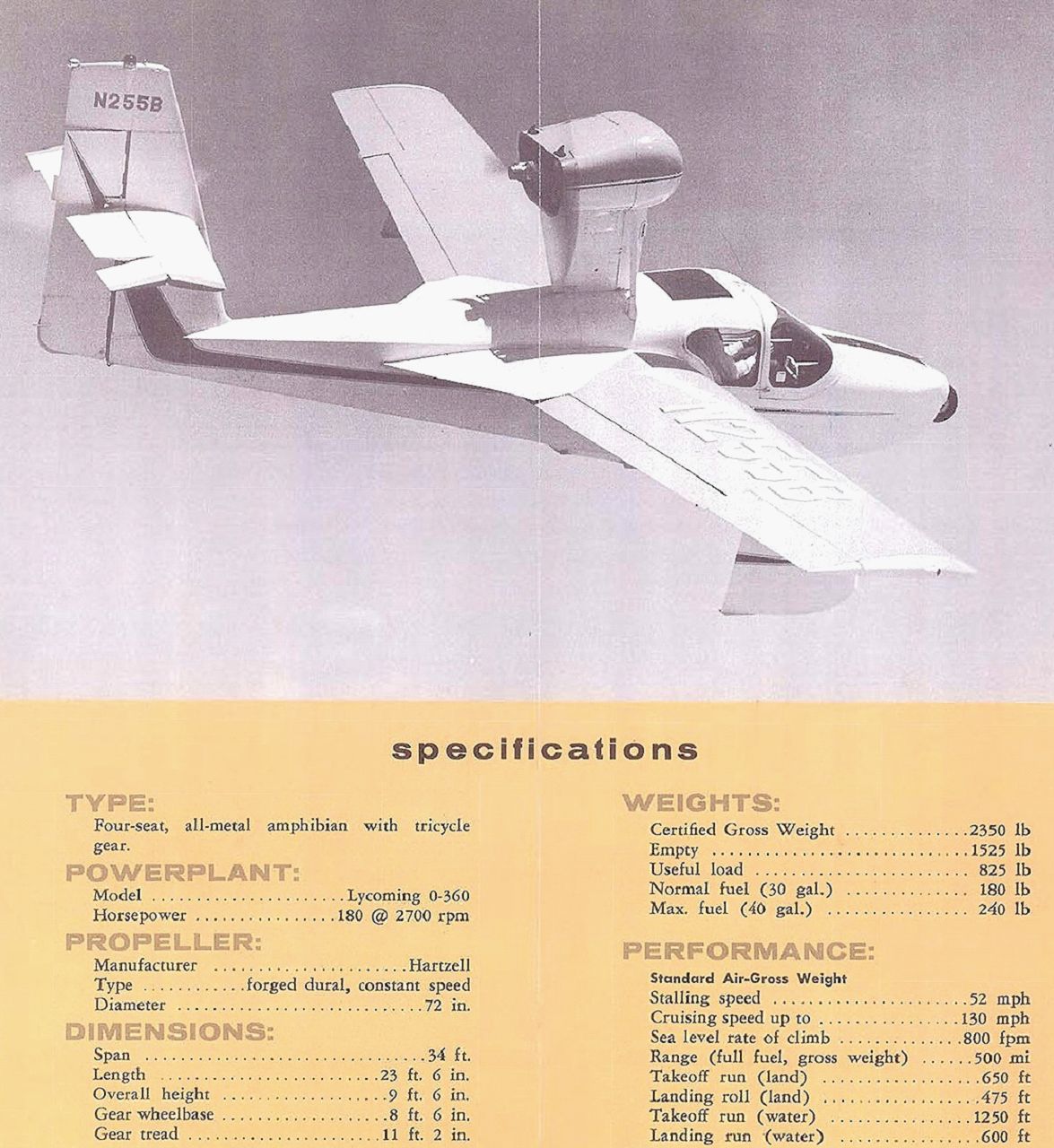

The Colonial C-2 Skimmer was small, 2/3 seat, single-engine amphibian aircraft built by the Colonial Aircraft Corporation. Originally located at Huntington Station, Long Island, New York, Colonial Aircraft was founded in 1948 by a group of men who worked at the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation. Headed by a man named David Thurston, Colonial Aircraft was formed to take up the work on small, civilian aircraft projects that had recently be dropped by Grumman. Working in their spare time, the group’s first product was the Colonial C-1 Skimmer. First flown on 17 July 1948, the Skimmer had an unusual layout, with its single, 150-horsepower, Lycoming engine mounted as a pusher in a pod above the fuselage. It took a while, but on 19 September 1955, the CAA issued an Approved Type Certificate Number 1A13 to the C-1 Skimmer. Thurston, who had resigned from Grumman in January 1955, to fully dedicate himself to Colonial Aircraft, which in the meantime had been moved up to Sanford, Maine, tweaked the original design to produce the C-2 Skimmer. Outwardly identical to the C-1, the C-2 had a number of improvements, including a slightly modified cockpit, with four seats now, and power from a 180-horsepower, Lycoming engine. An updated Approved Type Certificate was issued on 24 December 1957. In all, some 22 C-1, and 20 C-2 Skimmers were built. In October 1959, the Approved Type Certificate went through the first of many ownership changes, the first of these new owners being the Lake Aircraft Corporation, which developed the C-2 into what was the first in a long line of Lake LA-series of small amphibian aircraft.

Frank Bass’ Model C-2 Skimmer – Serial Number 142 – was originally purchased from Colonial Aircraft on 7 July 1959, by the Trans Air Corporation, of New Orleans, Louisiana, who in turn sold it to Bass two months later, on 9 September. Bass duly applied for and received a FAA aircraft registration, issued on 17 November 1959. Extant FAA aircraft inspection forms indicate that under Bass’ ownership, the C-2 Skimmer was subject to proper periodic FAA inspections, and was always deemed “airworthy.” The last recorded inspection – on 10 April 1962 – noted that the airframe had logged a total time of 415.2 hours. There should have been one more annual inspection completed before Bass embarked on the above described flights, but this form has not been found.

Bass went missing on the first leg of a long flight that was presumably to terminate at Andros Island. Taking off from San Juan (please refer to the chart provided), most likely from the Isla Grande Airport, Bass had planned to stop for fuel on South Caicos Island, in the Turks and Caicos Islands. Bass had apparently done this flight before, and told friends that he liked to fly westbound hugging the north coast of Puerto Rico, hop across the Mona Passage, and then hug the north coast of the Dominican Republic. This route would allow for ground referenced navigation, as well as giving Bass a place to go to in case of an inflight emergency. Once he reached a point along the Dominican coast, almost directly south of the Turks and Caicos, he would turn north and set coarse for the small island of South Caicos. Using this method, the longest over water stretch outside of reasonable gliding distance to land was around 95 nm. Plus, this shorter over water leg allowed less time with no landmarks by which to navigate, and thus less chance of drifting off course. On this flight, however, he told people that due to his recent troubles in the Dominican Republic, he would not fly his usual route, but rather direct from San Juan to the Turks and Caicos. This direct leg was around 365 NM, almost all of which was beyond gliding distance to land, and beyond any terrestrial landmarks. The factory brochure for the C-2 Skimmer states that with full fuel – 40 gallons – and at maximum gross weight – 2350 pounds – the aircraft had a range of 500 statute miles, or 434 nm. So, by either route, although it was certainly doable, Bass was pushing the envelope as far as the C-2’s range was concerned. Unforeseen weather, particularly adverse winds, could have been a problem.

While the Colonial Skimmer was a small, light aircraft, it was still designed to operate off of water, so if Bass got lost and ran out of gas, he still had a decent chance of executing, and surviving, an open ocean landing. Depending on the sea state, and the amount of pounding the airframe endured while it was on the water, Bass could have survived for some time. While the Skimmer presumably had at least a communications radio, no transmissions, emergency or otherwise, were heard. It is not known if the Skimmer had any, at least basic for the day, navigation radios. All of this is speculation, of course.

Even after the disappearance of Bass, his investments and business up in Cinco Bayou and Fort Walton Beach continued to do quite well, at one point being valued in excess of a half a million dollars, until one by one, without his management, they had to be closed down. The 17 August 1967 edition of the FAA’s airport directory noted that the “Ft. Walton Beach – Frank Bass SPB [seaplane base]” was abandoned, and should not be considered for use. Bass’ two sons, Donald Bass and Jerry Newman, both of Grand Prairie, Texas, flew down to Puerto Rico to search for traces of their father. About the only thing they found was that their father’s apartment was devoid of any of his personal items, and that he had told his fiancée that he had to be up in Arkansas in early 1964, to attend to some matters concerning an inheritance. Bass’ brother, retired Admiral Raymond Bass, of Glendale, California, thought that Bass was again being held somewhere in the Dominican Republic, Cuba or Haiti. Admiral Bass used his contacts in the Department of State to make inquiries, all of which turned up blank. Meanwhile, back up in Fort Walton Beach, there was a rumor circulating around that Bass had a small fortune in government bonds stashed somewhere on one of his properties. While several people joined in the search, nothing was ever found.

So, whatever did happen to Frank Bass? The simple answer as to what happened to this apparently normal, everyday Florida businessman is unknown. Was he, as some of the evidence presents, a man with a deep-seated desire to see communism swept out of the Caribbean, willing to put his life on the line for the cause? Or, was he a simple soldier of fortune? Or, neither? Did he work for the government, or did he work for himself? The answers to those questions are rather elusive. Finally, what happened on that last flight? Bad weather, airplane problems, or was it an error in navigation that led to fuel exhaustion? Did somebody sabotage Bass’ Skimmer? Perhaps, as some suggest, Frank Bass was never going to fly up to South Caicos Island, as his flight plan said. Instead, according to some local hometown chatter, he was flying out to the west on another clandestine mission, back to the Dominican Republic, or perhaps as far as Cuba. The mystery continues.

Know more of the Frank Bass story? Drop us a line at: contact@logbookmag.com

Special thanks go out to the great folks who work at the West Florida Public Library, and the University of West Florida Library, all of whom provided kind assistance with the preparation of this article.