One of the earliest companies to fly passenger service in Honduras and perhaps Central America was the little known “Compañía Aérea Hondureña.” The reasons for its obscurity may be attributed to the fact that it was owned by an American firm, the “Tela Rail Road Company”, which was itself a subsidiary of the famous “United Fruit Company.” Another reason may be that it was only “officially” in business from 1927 to 1932.

United Fruit officials had become aware early on of the need for a faster method of travel between Tela and Tegucigalpa. At the time, a person traveling from Tegucigalpa to Tela would head northwest by dirt road, across a mountain range and come down on the other side at the valley of Comayagua. From Comayagua he would continue to Siguatepeque and up another chain of mountains until he arrived at Lake Yojoa. He would then take a boat across the lake and continue by land across more mountainous terrain until he arrived at the Sula valley. He would then head north and then northeast across the hot and humid valley, arriving at Tela three to five days after his departure. The same trip by plane would normally take less than two hours.

The beginnings of the “airline” can be traced back to 1924 when the Tela RR Co. bought two Lincoln Standards. One equipped with a Hispano-Suiza motor and the other with a Wright E-4 motor. There was also a four-passenger plane (possibly an L-S-5). They were given the numbers 1 through 3, with the four-passenger plane being #1. This machine was lost when it caught fire while landing at Tegucigalpa. These airplanes were purchased to fly company mail and officials between Tela, the company’s headquarters, and the company’s other offices in Honduras.

The maintenance and operation of these airplanes were the responsibility of a pilot by the name of Christopher V. Pickup. Mr. Pickup was not too fond of Honduras and was understood to be generally unhappy with his employment. He felt the country was very wild and primitive. In July of 1925, he wrote a letter to a magazine critical of aviation in Honduras. An excerpt of his account follows: “Honduras at the present time is still very crude and much handicapped by the ignorance of the owners of the machines regarding flying in general… Emergency fields are another great drawback. There are few that a plane could land in maybe safely, maybe not. They are mostly covered here and there with stumps, holes and great trees or a new growth of brush and tropical vegetation. Should one land more or less safely in one of these places, then your trouble begins- walking in- into almost anything. The country is unsettled and wild and the few scattered native huts would probably be more of a hindrance than help, as the people in general are very ignorant and distrustful. They think little of killing one another, so the chance a Gringo would have in a place like that would be very slim indeed. Within the radius of forty miles, I know of only two fields suitable for even a Standard, and they are very small and obstructed, full of holes and high grass. We are using three wheeled landing gears and they help a great deal in places like that. The pilot must do practically all the mechanical work, at least he must know how to do it. True there is a mechanic here, a man whose experience is largely on gasoline motor- cars used on the railroad track. He calls the ailerons “them flappin’ things,” and all else accordingly… We live in Tela, a United Fruit Company port, and a great deal like a small mining town in the States. The Americans all live in colony houses all practically alike. They also own the dairy, truck garden, commissary and everything and anything that is needed must be bought from them at a very unreasonable price.” Needless to say, Mr. Pickup did not endear himself to his employers who were soon looking for a new pilot.

In January 1926 the position for chief pilot became available. One of the applicants for the job was Sumner B. Morgan. Sunny, as he was known to his friends, had always disliked cold weather and had decided early on to try to make a living in a warm climate. The opening for the position of chief pilot came at the right time as he was just ending his relationship with Dr. Pounds in the famous first Honduras airmail service. This service lasted from May to December 1925. The failure of this venture led him to seek better employment elsewhere. In an ironic twist of fate one of the other supposed applicants, who was turned down as “unsatisfactory”, would soon become the most famous man on earth. His name was Charles A. Lindbergh. He would later surmise upon his return to Honduras in 1928, that if he had been successful in getting the job in 1926, he would probably never have flown the Atlantic.

After reviewing the qualifications of various applicants, Morgan was hired. Sunny had been involved in the aviation business since 1916, at which time he worked as a motor tester for the Curtiss Aero-Motor Corporation. He also studied motor design at Cornell University in 1917. Other jobs to his credit were: flying for the Philadelphia Aero Service Corporation, mechanic for the U.S. Airmail Service, and pilot and mechanic for the New York City Police Reserve. In 1924 he was qualified as a Naval Aviator at Fort Hamilton, New York. He was also an expert mechanic of aeronautical engines. The fact that he was already experienced with flying in Honduras probably sealed the position for him.

Morgan moved into one of the United Fruit Company’s cottages at Tela. There, he would soon enjoy the relative comforts of company life. The town of Tela was an agricultural enclave. There were large steam ships regularly docked at the wharf, The Rail Road Company’s yards were buzzing with activity, cars and trucks were a common sight and soon the most modern of all transport methods would be a regular sight overhead. Life in Tela was quite a contrast from life in the rest of Honduras where most people had rarely, if ever, seen a train, ship or plane.

Sunny quickly settled into his new surroundings and was soon earning a good salary. His base pay was $300.00 a month plus commissions, which on occasion amounted to more than $1,000 a month (more than $10,000 in 2001 dollars). Moving to Tela was a big change from the precarious life Sunny had been living in Tegucigalpa and Puerto Cortes. The company provided a stable job and some of the comforts that Americans were used to enjoying. There was a company mess hall, telegraph and telephone service, a 160-bed hospital, a racetrack, golf course, etc. Tela was the port where the Company’s ships docked to load bananas and unload mail and passengers. There was even a red light district called Punta Caliente (hot point). This was a big change from his days with the Central American Airlines, which was a seat of the pants operation.

On February 2nd 1926, Sunny took Standard #3 up for a twenty-five minute test flight over Tela. On the 5th he made his first flight to Tegucigalpa carrying company mail. This would be the beginning of a busy schedule for Sunny and the Standard’s as there were flights almost every other day. The planes made regular trips between Tela, San Pedro, and Tegucigalpa with occasional visits to other towns such as La Ceiba, San Lorenzo, Puerto Castilla, Puerto Cortés, etc.

The company had a landing field and hangar at Puerto Arturo. However, this field was inconveniently located about three miles distant from town. This led to the decision to build a more accessible landing strip just outside of Tela. the new field was named Aviation Park. The landing strip, located about ¾ of a mile west of town, bisected a horse race track which had stands for spectators on the south side. The runway ran NE/SW and measured 300 by 1800 feet. The clay surface was kept level by the use of a tractor equipped with a heavy steel roller. The field was suitable for use in any weather as it had excellent drainage. There was a hangar on the southeast side measuring 55 by 40 by 12 feet with a wind cone marker. Pilots had to be careful to avoid the 250 foot radio tower which was located about 400 yards northeast of the runway.

Flying in Honduras was not an easy undertaking. The tropical climate of the country meant that severe storms could form very quickly. Sunny used to say that the weather around the coast was “bumpy as the deuce”. The mountainous nature of the country left very few areas where one could land in the event of an emergency. On April 13th 1926 Sunny set out from Tela to Tegucigalpa on a flight that normally took a little over two hours to complete.

On this day, however, he encountered a severe storm with strong head winds. Sunny struggled to reach Tegucigalpa until he ran out of gas, causing him to make a forced landing at San Antonio, Comayagua, a town located about 40 miles north-west of Tegucigalpa. By that point he had been flying for three hours and twenty minutes. Four days later, after making minor repairs and securing gas, he again set out for Tegucigalpa completing the trip in 35 minutes. Ten days later bad luck was with him again. In a letter to his brother Henry he wrote: “Last Wednesday (April 27) I started out again and got over the far end of the field and the motor quit me dead, and I only had thirty feet altitude. It was right over some trees and I had to stretch my glide over a creek and had to land in a patch of ground about 50 feet Square. Well, I took off my landing gear, slid along on the nose of the plane for about fifteen feet, and then went over on my back with the gas and oil spraying all over hell’s half acre. I got out in one damn hurry believe me! and the only mark I got was the hide taken off my right shin in two places, didn’t even get the regulation black eyes. Fortunately, the plane didn’t catch fire and I can fix it up for about three hundred dollars, but I don’t think that they are going to repair it as they are planning on the new plane and don’t care to waste money on the old ones.”

Company officials were already considering buying a new plane, consequently, this incident accelerated the process. Sunny and R.H. Goodell, General Manager of the United Fruit Company in Honduras, arranged a trip to the States. After arriving in the U.S., a visit was made to the Atlantic Aircraft Corporation, which was the Fokker distributor at Teterboro, New Jersey. The Fokker Universal seemed to meet all the requirements they had in mind. It had a useful load of 1,500 lbs., a maximum speed of 118 M.P.H., and a comfortable cruising range of 600 miles. The cabin was heated and had accommodations for six passengers. The aircraft was a high wing monoplane with an enclosed passenger cabin – but with an open cockpit for the pilot. After taking the plane up for a test they decided it met all the requirements and a purchase order was signed.

Sunny decided to fly the plane, which was named The Tela, from New Jersey to Washington, D.C. in order to get acquainted with its flying qualities, fuel consumption and speed. After extensive testing at Anacostia field the plane set off for New Orleans at 3 a.m. on Tuesday, October 11th, with Morgan acting as pilot and Lieutenant A.P. Flagg of the Navy Department acting as co-pilot and navigator. After fighting head winds and rain storms most of the way from Washington, The Tela was forced to turn back and land in Montgomery, Alabama. The aviators arrived at Callender field in New Orleans at 1:28 p.m. on Wednesday, October 12th. The flight was an important one and had been billed as a cross-country flight from Washington to New Orleans.

Upon their arrival, several important company officials and New Orleans dignitaries greeted the aviators and the Louisiana Aeronautical Association gave a luncheon in their honor. The plane was then dismantled and placed aboard the steam ship Abangarez for delivery to Tela . Once in Tela, the plane was reassembled and quickly put to use transporting Company mail and officials around the various offices in Honduras. This plane made almost daily trips and was a regular sight at different landing fields in the country. The Tela was a source of pride for the Company and was used very effectively as a public relations tool whenever dignitaries or important people were in town.

What might have been

Sunny was always looking for ways to further the aviation industry. In November 1927 he wrote a five-page letter to Crawford H. Ellis, VP of United Fruit, suggesting the establishment of a company-run airline. The route would begin in New Orleans and make its way down the Atlantic coast all the way to Colombia, South America. Morgan suggested the use of Dornier-Wal monoplane flying boats as he felt the public would feel safer flying over water. These planes had an empty weight of 7,700 pounds and a similar useful load. They also had a flying range of 1,800 miles and a cruising speed of 125 miles per hour. He also suggested the use of air-cooled Pratt & Whitney Wasp or Hornet motors as he felt the added horsepower would allow the engines to run at 75 % of maximum power, thereby reducing time between overhauls.

As to the sources of revenue for the service, he wrote, “In the course of time, we could endeavor to secure the different government contracts for carrying mail by plane, and providing this is possible, it will more than pay the operating expenses. Other big financial features would be transporting of currency for the Central American bankers and merchants, small express packages, special delivery letters and drafts. The passenger business would be a type of service that would have to be built up and an advertising, educational program followed until the general public saw the advantages in such a service in the saving of time and discomforts with which a tropical traveler now has to contend. However, the company should bear in mind that carrying weight for weight, there is a greater financial return in carrying mail and currency than in the passenger traffic Possibly the benefit the Company derives from these operations are of greater interest than the revenue. If a regular service were established, the Company would have the benefit of a fast and efficient mail service between all division headquarters in the tropics and their main offices in the United States. A fast service could be operated from Colombia, South America, to New Orleans, La., touching at company divisions along the route at from two and one half to four days, and if night flying were undertaken, this time would of course be lessened. Company mail would be carried at no expense and handled as at present by the Great White Fleet. The transferring of company officials from divisions to other points, which require their presence, would be in itself a great saving to the company both in time and money. If a sub-division or subsidiary company should be formed to handle this department of service, it could still use the U.F. Co. and flag insignia. In this case, it would mean “United Flying Company.”

Unfortunately, the company VP, George Chittenden, did not agree with Sunny. He responded, “Mr. Ellis has forwarded me your letter to him dated November 17th with enclosures regarding proposal to operate aeroplane service in Central America under the direction of a Company, which would be a subsidiary of the United Fruit Company. It would, of course, be very nice for us to have such a service, which would ensure prompt delivery of our mails, but, on the other hand, it would lead to a series of headaches. International air traffic such as you suggest would, I am afraid, run into snags before it had been in operation a month. The various Central American countries are very jealous of their own rights and would, I believe, in time put many obstacles in the way of an air service.”

Mr. Chittenden, as we know, was wrong in assuming that the Central Americans would not welcome such a service. This was shown by Pan-Am two years later. Had company officials acted on Sunny’s suggestions, perhaps the United Fruit Co. would have occupied a great place in aviation history. They eventually implemented a scaled down version of his proposal in Honduras with the “Compañía Aérea Hondureña.”

A Distinguished Visitor

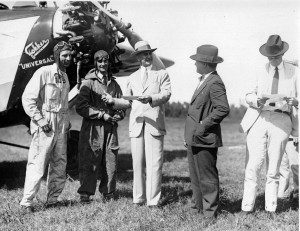

In January 4th, 1928, Charles Lindbergh paid a visit to Honduras as part of his goodwill tour of Latin America and Sunny flew to Tegucigalpa to greet him. Lindbergh spent a couple of busy days at the Capital. U.S. ambassador Summerlin gave a special dinner in his honor. He was also asked to give a speech to Congress and had a special dance given in his honor at the Casino Hondureño. Three days after his arrival Lindbergh headed to Toncontín for his departure to Nicaragua. The crowd that had gathered shouted “Vivas” for the flier, for the United States, for Honduras and for President Baraona. The crowd rushed up to shake Col. Lindbergh’s hand. Meanwhile, the Ryan’s engine had been tuned and – marshaled by soldiers – the crowd fell back to give room for the start of the Spirit of St. Louis and the Fokker which was bearing Public Works Minister Moncada and Under Secretary of War Pineda.

As ambassador Summerlin bade good-bye to Col. Lindbergh, President Baraona broke through the crowd in which he had been caught, rushed between the two planes and shook Col. Lindbergh’s hand. A score of girls ran up and pushed through the broken ranks. Col. Lindbergh had started saying good-bye, but when he caught site of the girls he broke away and ran to the door of the plane’s cockpit. Officials waved the girls back. Then, following the Fokker, Col. Lindbergh taxied to the south end of the field and took off against the northerly breeze. The skies were clear and sunny, and after circling the city to gain altitude, he headed south towards the Gulf of Fonseca on his way to Nicaragua, the crowd yelling loudly all the while. The Spirit of St. Louis disappeared from sight at 11:45. At the time, Lindbergh was probably the most famous dignitary to visit Honduras.

Flying the Mail

In 1925 the government of Honduras and the Tela Rail Road Company had signed a contract in which the company agreed to transport up to ten kilos of correspondence on each trip made by its airplanes between Tela and the capital. It is believed, however, that the company never really fulfilled the agreement. This despite the fact that Morgan’s logbooks show that mail was carried on just about every flight. It is possible, however, that the mail carried was mostly company mail.

The Postmaster General, once aware of the situation, met with company officials to insist on compliance. As a result, the second airmail service was begun on May 15, 1928 between Tegucigalpa and Tela. There were two trips made weekly and the route was later extended to San Pedro Sula (the company was paid a small sum for this service). There were no special stamps issued for this service and covers carried by air can only be distinguished by the “CORREO AEREO” hand stamp which was applied to each cover. It has been reported that the second airmail service was also irregular and finally became non-existent. The Postmaster General’s report for fiscal year 1930-1931 states that flights were made at intervals, or rather when the Tela RR Co. possessed an airplane. He also states that the company had sold its plane, thus terminating this means of transporting the mails. This last statement seems unusual as the company was at its peak and had three planes in service – the Fokker, the Bellanca and the Stearman.

Morgan also transported the mail for the Legation of the United States in Honduras. In June 1927, he received a letter from the Charge d’affaires Herschel Johnson, it read- “Sir: It gives me much pleasure to make a matter of record the constant courtesy you have extended to this legation since February 1926 in transporting its official mail by aeroplane from Tegucigalpa to Tela. Your service has been greatly appreciated and has materially aided the Legation in forwarding timely reports to the Department of State.”

The Beginnings of Tourism

The United Fruit Co. was the biggest fruit exporter in Honduras and had a fleet of ships called “The Great White Fleet”. These refrigerated ships transported fruit from Honduras and other countries to New Orleans, Philadelphia, New York and Boston. In addition to transporting fruit, the ships were equipped with cabins for paying passengers. In the early 1900’s the company had begun a campaign aimed at promoting travel between the U.S. and exotic places such as, Jamaica, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, etc. The company had plantations in all of these countries and sought to increase it earnings by enticing tourists to visit these locales. Once off the ships, however, passengers were usually relegated to visiting towns close to the port of call. For many years these ships were the preferred mode of travel between the U.S. and Honduras until Pan-Am began its air service in 1929.

The Fruit Company saw an opportunity to extend its services to passengers wanting to visit the cities located in the interior of Honduras. R.H. Goodell, who had been instrumental in introducing aviation to the company, noticed that many of the flights were being made with only one official on board. Realizing this was wasteful he decided that paying passengers would help to offset the costs of operating the plane. It was at this point that an effort was begun to establish a bonafide airline-type of operation following Sunny’s suggestions. Honduran officials were at this point, encouraging the creation of the airline. Government officials would soon become regular users of the service.

On October 1, 1929 a Bellanca Pacemaker (NC-249M) was purchased. This was a thoroughly modern, high wing monoplane with an enclosed cabin. It was also capable of carrying four passengers at a relatively high speed. The acquisition of another plane necessitated the hiring of another pilot so Morgan recommended an old friend from the Philadelphia Aero Services Corporation. On September 19, 1929 Louis Maurice Robb was hired and given the task of flying the Fokker. Sunny was chief pilot and so he was given the more modern Bellanca. Again, this plane made regular trips and was kept in constant use.

The addition of another plane also necessitated the hiring of additional help to keep the planes in good order. It was at this time that Sunny’s brother, Henry, was hired. Henry was charged with keeping the hangar in order. He also did mechanical work on the planes. Much of this work is based on Henry’s detailed letters to his family. Henry arrived in Honduras at the end of 1929 and quickly came to enjoy Tela. He was a friendly person who had been actively involved in his high school’s theater groups and was well liked by his peers.

In a few years Tela had become a hub of activity. In 1929 Charles Lindbergh flew to various countries in Latin America, charting routes for Pan-Am. Tela became the stop for Honduras and was soon busy with international flights. The Pan-Am planes initially made three flights a week from Miami, greatly reducing mail delivery time from weeks to a couple of days. They were later reduced to Thursdays and Saturdays.

Sunny was still flying just as frequently as ever. His navigational skills were exceptional. However, he was occasionally forced down due to bad weather or malfunctions of the plane. On July 20, 1930 he had a somewhat comical incident. He wrote his mother, “I cracked up the Stearman landing gear over in the mountains and had to ride six hours mule-back in the rain over one hell of a mountain in the dark. Was I scared? Well I near p’d my panties, but it wouldn’t have shown as I was soaking wet and who could tell weather it was rain or not.”

In 1929 the head office in Boston decided to do an aerial survey of its plantations in Honduras. As the two passenger planes were busy making money for the company a Stearman C-2 bi-plane was purchased and equipped with special brackets to hold a large, high-resolution camera. The Hamilton Maxwell firm of Stamford, Connecticut was hired to organize the required personnel and to direct the tropical photographic activities and the preparation of the final maps in completed form.

The company’s hangars were soon busy with all the activities associated with the planes. It was at this point that the company decided to branch off and create the “Compañía Aérea Hondureña”. All of the planes had a winged logo painted on the side with a corresponding number in the center. The Fokker, – called the Tela- was #1, the Bellanca -called the Danny Boy- #2 and the Sterman #3. Ads were placed in various publications as well as the company’s brochures and business began to thrive. Before long, the service was operating as a regular airline with regular schedules.

Ads were placed in numerous publications, both in English and Spanish. One off the ads read: “Do your traveling between the North Coast and Tegucigalpa with the maximum of speed, comfort and safety offered by this modern mode of transportation. Cabin planes flown by expert aviators. Regular service to San Pedro Sula and Tela Tuesdays and Saturdays. The planes arriving from these points on Mondays and Fridays. Special trips to different points in Honduras or to the neighboring Republics may be arranged at any time. For detailed information address either: Tela, S. Pedro Sula or Tegucigalpa offices.”

On March 31, 1931 a devastating earthquake hit Nicaragua. The capital city, Managua, was leveled and approximately 2400 lives were lost. Compañía Aérea was quick to respond. Henry sent a letter home April the 5th in which he wrote: “Undoubtedly by now, you people have about all of the news concerning the Managua earthquake- that is, at least as much as I know about it. The day after it happened, Sunny flew there from Tegucigalpa, He says it is terrible, scarcely a building left standing and fire was making fast work of those that did go through the shock. The marines are having a bad time fighting the fire, as the water mains are all broken. Few of the people had earthquake insurance so some people are setting fire to their buildings to collect what money they can. Sunny flew over with radio equipment and a couple of marine officers. Robb flew over the following day, so Compañía Aérea was pretty well represented. P.A.A. are sending special planes all of the time loaded with medical supplies and such. For a time, the marines were performing amputations with common wood saws without any anesthetic, using just salt water”. He continued on the 12th: “I’m anxious to get the Telegram and see what it has to say about the Managua earthquake. Sunny made another trip last week. Will Rogers is over there and will likely come back by way of Tela on the P.A.A. plane.”

The head office had big plans for Compañía Aérea Hondureña. The feasibility of a company run airline was beginning to look like a distinct possibility. In fact, the Company was doing so well, that it became apparent that another plane would soon be needed. On December 15, 1931 Sunny took delivery of a Bellanca CH-400 Skyrocket (NC-12636) at the factory in New Castle, Delaware. The Skyrocket had room for five passengers plus the pilot and was equipped with a Wasp 420 H.P. motor.

This plane joined the fleet and was also flown extensively. It even made occasional trips to El Salvador, Nicaragua and Guatemala. The airline continued to build up the business and was becoming profitable. In a few short years, it had become the desired mode of travel for civilians, and military and government officials. It was in fact, the only existing airline in the country.

Dirty Politics

In 1929 Tiburcio Carías Andino won the Honduran presidential elections. Peasant rebels in the interior of the country (supporters of Dr.Vicente Mejia Colíndres) refused to relinquish power; Lowell Yerex, a New Zealand pilot living in Honduras, offered to fly a recognizance mission for Carías. While flying over rebel positions one of the rebels managed to get off a “lucky” shot which struck the windshield and sent a piece of glass flying into Yerex’s eye causing him to lose vision in that eye. After this incident, Carias felt eternally indebted to Yerex. Yerex was at that point starting TACA airlines and decided to follow Pan-Am’s example of buying up or driving its competitors out of business. However, it was unable to buy the Compañía Aérea Hondureña as this was owned by the United Fruit Co. At the end of 1932,Yerex decided to call in a favor and asked Carias to order the United Fruit Co. to stop carrying commercial cargo and passengers and limit itself to conducting only company business.

Yerex persuaded Carías by promising to make TACA the national airline of Honduras. Carías had many faults (among which was his later brutal dictatorship and murder of hundreds of civilians); however, he saw the benefit the service would bring to a country as mountainous as Honduras. Carias agreed to Yerex’s proposal and requested that the United Fruit Company cease its airline operations.

In May 1932, Henry wrote a letter to his family in which he stated- “It’s rather a blow to us, Sunny most of all, I think- so maybe it would be best not to mention it unless Sunny writes you. Compañía Aérea has undergone some radical changes in the past week. The Boston office has decided that it would be best if we discontinued the passenger service altogether and keep on with the company business only. This doesn’t warrant flying both planes so, for the time being at least, the Fokker is not to fly. This means, of course, that Robb will have to go. It all seems a shame after building up the business for five or six years and getting a good reputation in the country, and Sunny has done a lot to help build it up too. The reason the Company wants to make the change is because of political feeling against a fruit company owned airline. Public opinion here seems to be favorable and we have generally plenty of passengers but the Boston office doesn’t seem to want to consider that side of it. Compañía Aérea has been a paying proposition and next year would have undoubtedly boomed.”

United Fruit officials were aware that Carias was an impulsive, irrational man who had a tendency to act on feelings alone. It was for this reason that it was decided not to risk the company’s multimillion-dollar fruit operations for the relatively small earnings of the airline.

A Sad Ending

Henry had been sick for some time and the company doctors had been unable to find the cause of his illness. At the end of 1932, he headed back to the States in an effort to get better medical care. Sunny accompanied him and they spent Christmas at the family home in Elmira. While there, Henry received many get-well letters from his friends in Tela. During this time Sunny, concerned about his job in light of his friend Robb’s recent release and the changes in company policy, concluded that now was a good time to realize his dream and start his own airline. He cashed in his company stock and purchased a Ford Tri-Motor for $5000.00 with which he was to start Morgan Airlines. As he was flying back to Honduras he received a telegram at the airport at Brownsville, Texas from his sister Gladys. It read- “Henry died this morning six o’clock.” Sadly, the same fate awaited the airline.

In 1933 the Fokker and Bellanca Pacemaker were sold to “Empresa Dean”, while the Bellanca Skyrocket was transferred to the “Compañía Agrícola Ulúa,” another subsidiary of the United Fruit Company. The Empresa Dean was then bought out by TACA in 1934. Thus, the short-lived Compañía Aérea Hondureña came to an undeserved and premature end.

As a side note, after leaving the Tela RR. Co. Sunny started Morgan Airlines early in 1933. Yerex was not happy about the competition as he felt Morgan airlines, with its big Ford Tri-Motor (NC-7120), was hampering his plans to monopolize the airline industry in Honduras. The two men soon came to dislike each other. Morgan airlines was successful enough that a Bellanca was also purchased. Sunny also hired several American pilots and, for a short time, even the famous Honduran pilot, Lisandro Garay. Morgan airlines advertised in the daily newspapers and was very competitive with TACA. In fact, some people preferred Morgan to the competition, as they knew he had flown successfully in Honduras for many years without any major mishaps. Unfortunately, his success would soon be the cause of his demise. In 1937, Sunny was falsely accused of plotting against the government and TACA (possibly by Yerex’s people). He was jailed for over one month in Tegucigalpa and was finally ordered to leave the country permanently. This marked the end of Sunny’s glorious aviation career in Honduras.

Sources

- Aviation Magazine, Christopher V. Pickup, July 1925.

- The Black Honduras, Irving I. Green-1961, Collector Club Philatelist.

- Miguel Paz interview on 8-Apr-1986.

- Central American Pilot, Gov. Printing Office-1932.

- Unifruitco Magazine, November 1927.

Acknowledgements

Most of this work is based on Sunny and Henry Morgan’s personal letters, documents and photos. These items were saved from the trash heap by the wisdom of Mr. Norman Fairbanks (Sunny’s nephew). Special thanks to Ann and Richard Weber for giving me the Morgan Airlines office sign as a Christmas present. I would also like to thank Dr.Gary Khun and Dan Hagedorn for their contributions, and Mr. Richard A. Washburn for the airmail section.

I knew Sunny when when he was living in Managua , I lived in Chinandega Nicaragua, he was a friend of my family, his sister lived down the street from me , and when I went to visit him , he showed me the photo’s of Linburge ,and the Marines landing in Nicaragua. I have had the luck to buy a good part of the early items, Sunny owned. He told me they called Linburge lucky, because he wrecked less then most at that time. My name is Daniel Cullip and you can contact me at 859-533-5445.