In 1931, the U.S. Army Air Corps -USAAC- wanted a small pursuit fighter capable of reaching and effectively attack the fast bombers that were currently in production, like the Y1B-9A. Boeing’s answer to that requirement was the diminutive Model 248, a low-wing monoplane with an aluminum monocoque fuselage that incorporated many of the important features that would become standard on aircraft used in WWII. Strangely, the 248 also shared some characteristics of the older biplanes, like an open cockpit, externally wire-braced wings and a sturdy fixed landing gear. The prototype, designated as P-936 by the U.S. Army Air Corps, took to the skies for the first time on March 20, 1932. Shortly after, Boeing completed two more prototypes, which began extensive testing.

Powered by a 525 hp Pratt & Whitney R-1340-21 “Wasp” radial engine, the P-936 soon proved to be a rather fast and agile fighter, with a top speed of 234 mph. However, its clean lines and short wings also made it a “hot” airplane, especially during landings, as it had a minimum speed of 82 mph, which was considered “too fast” by the Army pilots of the day. Its narrow-tracked main landing gear also posed a challenge, since the airplane tended to become uncontrollable as soon as it touched down. To make things even worse, due to its short nose, it tended to flip forward and roll onto its back, sometimes crushing the pilot in the cockpit.

In order to remedy the airplane’s shortcomings, Boeing designed a set of flaps that reduced the airplane’s landing speed to a more acceptable 73 mph and installed a reinforced headrest, eight inches taller than those on the early prototypes, for preventing the pilot from breaking his neck in case of a nose over. Boeing also replaced the old R-1340-21 engine with the more powerful R-1340-27. This heavily modified design, named by the company as Model 266, was the one that the U.S. Army Air Corps finally ordered. Thus, in January 11, 1933, Boeing commenced the production of 111 airplanes, which received the official Army designation of P-26A.

Less than a year later, the first batch of P-26As was delivered to the 20th Pursuit Squadron, based at Barksdale Field, Louisiana, being followed by another batch delivered to the 1st Pursuit Group based at Selfridge Field, Michigan, and another to the 17th Pursuit Group based at March Field, California. Ultimately, 22 squadrons flew the P-26A, nicknamed “Peashooter” by the Army pilots, allegedly due the blast tubes of its two internally mounted M1919 Browning machine guns.

The next iteration of the design, named P-26B, was to be equipped with a fuel-injected version of the “Wasp” engine in order to improve the airplane’s performance at higher altitudes. However, only three of the new engines were initially available. The following 25 airframes were completed as P-26Cs, designed to accept the fuel-injected engine but equipped with the carbureted engine of the P-26A. As more fuel-injected engines became available, some of the P-26Cs were subsequently upgraded to the P-26B standard.

A truly transition aircraft, the Peashooter soon found itself displaced by far more advanced designs like the Seversky P-35 and, later on, like the Curtiss P-36 and P-40. In fact, by mid-1938, the P-26s began to be transferred to fighter squadrons at remote overseas bases like Wheeler Field in Oahu, Hawaii, and Albrook Field in the Panama Canal Zone. When Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese on December 7, 1941, only eleven P-26s remained airworthy with the 18th Pursuit Group at Wheeler Field (of which six were destroyed and one sustained heavy damage during the attack) and 10 with the 32nd Pursuit Group at Albrook Field. Lastly, no less than 28 P-26s were based at Clark Field in Luzon, the Philippines, but many of them were destroyed by the Japanese during a surprise attack on December 8, 1941. The surviving airplanes, no more than 12, were then transferred to the 6th Fighter Squadron of the Philippine Army Air Corps. Shortly after, three kills were claimed by a pair of philippine pilots, the victims being a Japanese Mitsubishi G3M bomber and two A6M2 Zeke fighters.

Guatemalan Army Aviation Corps Service

By February 1942, the 10 P-26As assigned to the 32nd Pursuit Group at Albrook Field still were considered first-line equipment and conducted tactical missions regularly, albeit while assigned to remote locations. Three of them were assigned to San José, Costa Rica, as part of a detachment of the Panama Interceptor Command, where they carried out airfield defense duties. Six others, also part of the Panama Interceptor Command detachment, had been deployed to Guatemala City, Guatemala, where they provided cover for the entire B-17 bomber force that patrolled the waters of Central America and the northern cone of South America, as well as the Panama Canal. By that time, however, the P-26s had become a maintenance nightmare and only two or three were usually airworthy at La Aurora airport in Guatemala City, and only one at the Port San José airbase, in the Pacific Coast of the country.

It was at this point that the Guatemalan government, led by General Jorge Ubico, became interested in acquiring some of the P-26s for the Guatemalan Army Aviation Corps -GAAC- which, at the time, seemed to be trapped in the 1930s, technologically speaking. The service still operated a handful of Waco VPF-7s biplanes, and no less than eleven Ryan ST-As as its fighter component, organized in two pursuit squadrons. Additionally, the GAAC operated a bizarre array of obsolete types that included two Boeing-Stearman PT-17s, a pair of Vultee BT-15s, a few inefficient Caudron C.601s -that were grounded most of the time due to safety issues- and a couple of very old Waco UMF-3s that were used as light attack planes. With this in mind, it came as no surprise the fact that the GAAC leadership would try to add more fighters to the service’s inventory, taking advantage of an incipient military aid program launched by the U.S. right after the outbreak of WWII, called Lend-Lease.

However, there was a U.S. congressional prohibition on transferring lethal armament to Latin American countries, except to Brazil and Mexico, and the Guatemalan request for the P-26 fighters was turned down initially. Despite this, the leadership of the U.S. Army Air Force (as the USAAC had been redesignated) didn’t want to miss the opportunity of getting rid of the old planes and, at the same time, show some appreciation for the Guatemalan government for having authorized the USAAF to establish two -well situated- air bases in the country as unconditional cooperation to the war efforts (Guatemala declared war to Japan a day after the Pearl Harbor attack, and to Germany on December 18th.)

Since the congressional ban didn’t include training planes, the USAAF leadership at Albrook came up with a trick to circumvent it: The Peashooters were temporarily redesignated as trainers. It was in that way that the P-26s -at least on the transfer documents- became Boeing PT-26 Primary Trainers prior to be handed over to the GAAC. Thus, by November 1942, the paperwork for the sale was already under way and the USAAF began a thorough overhauling and refurbishing work on the six Peashooters that were based at La Aurora.

The difficult delivery process of the airplanes, which comprised towing the first four of them from the Southeastern sector of La Aurora -where the USAAF base was located- to the La Aurora air base, less than a kilometer away, was carried out without incidents in April 1943. Two more airplanes followed the very same process in May, and a seventh machine -supposedly for spares- was flown crated from the Panama Canal Zone sometime later. This last P-26 was quickly made airworthy by the Guatemala mechanics; such was the fascination of the service’s leadership with its new fighters.

Upon entering in service with the GAAC, the P-26As were assigned to the 4th Squadron and received the following serials:

- 43 (Boeing C/N 1899, ex USAAC S/N 33-123)

- 44 (Boeing C/N 1911, ex USAAC S/N 33-135)

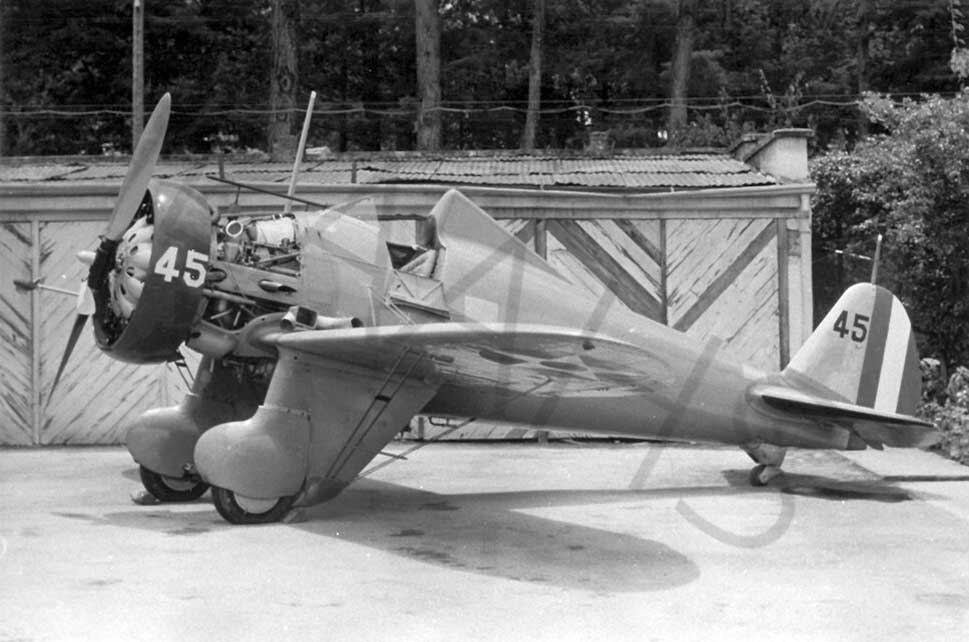

- 45 (Boeing C/N 1902, ex USAAC S/N 33-126)

- 46 (Boeing C/N 1908, ex USAAC S/N 33-132)

- 47 (Boeing C/N 1825, ex USAAC S/N 33-49)

- 48 (Boeing C/N 1851, ex USAAC S/N 33-75)

- 49 (Boeing C/N 1865, ex USAAC S/N 33-89)

The airplanes were handed over in the usual USAAF paint scheme of olive green overall, but the Guatemalan mechanics didn’t lose any time in adding a “personal” touch and painted the head of a Greek god on both sides of the fuselage of each airplane. Meanwhile, under the tutelage of USAAF advisors, the Guatemalan pilots began familiarizing with their new mounts, and by the end of the month, the first three had been checked out in the type. During the training process, however, the airplane carrying the serial 46 was damaged beyond repair while taxiing prior to taking off. According to witnesses, the P-26 stumbled into a small rut on the taxiway and the right landing gear collapsed. It was being piloted by Lt. René Sarmiento who, fortunately, walked out unharmed.

The Peashooters quickly became the GAAC’s pride and joy and the classic line-ups at La Aurora’s main ramp were a common sight upon arriving dignitaries. However, the airplanes were seldom flown due to the lack of qualified pilots. Additionally, the infamous handling characteristics of the P-26 during landings inspired respect -if not fear- in the reluctant Guatemalan aviators who much preferred to fly less byzantine machines like the VPF-7s and ST-As.

In any case, the USAAF advisors kept pushing the training program ahead, something that at times turned out to be very difficult due the pilots’ resistance to fly the Peashooters. However, in early 1944 there was a small improvement regarding the availability of trainees for the type, since the Ryan ST-As of the 2nd Squadron had been grounded due to their Menasco engines running out of hours. Thus, the pilots who were assigned to said unit were transferred to the 4th Squadron which, from then on, was manned by eleven officers and equipped with the six Peashooters.

Winds of Change

As the first half of 1944 was nearing its end, winds of democracy began blowing across Guatemala. The majority of its citizens grew tired of General Ubico, who had been in power for 13 years through rigged elections and other legal subterfuges, and began clamoring for a political change. Among their pleas were the four freedoms that the Allies were preaching in Europe against fascism. Then, numerous riots and protests exploded across the Capital but were quickly reduced by Ubico’s ferocious police. Persistence was the name of the game, however, and finally, on July 1st the unthinkable happened: General Ubico resigned under an insurmountable pressure on the part of the civilian sector of the society.

But the Ubico was really clever and covered his retreat by leaving behind a military junta composed by three of his most trusted generals: Federico Ponce, Eduardo Villagrán and Buenaventura Pineda. Of these, Ponce was the most ambitious of the three and he didn’t lose any time in trying to gain control of the presidency by bribing and threatening the congress. In July 4th the junta was disbanded and the Congress designated Ponce as the new president of Guatemala.

The Guatemalans learned rather quickly that Ponce was no different from Ubico. And as a new dictatorship was in the works, the university students and the organized sectors of the society took to the streets once again. They also approached and successfully gained the support of a group of young officers of the Guatemalan Army who, without hesitation, began planning a coup d’etat. Among these officers was the tanks commander of the Guardia de Honor garrison, something that implied a huge advantage over the bases loyal to Ponce, which were poorly equipped. Upon having everything ready and well rehearsed, they established October 19th as their D Day.

The role of the GAAC during the preparation of the coup is something that remains in deep mystery. Some historians say that the Aviation Corps’ commander, Colonel Rodolfo Mendoza, didn’t know about it. Some others say that he knew but decided to remain neutral and waited to see how it all ended, even when he had been decidedly pro-Ubico and most recently, pro-Ponce, in order to keep his job.

Whatever was the case, during the second week of October, the GAAC leadership organized a combat exercise that called for the deployment of the 1st and 4th Squadrons to the USAAF Air Base at Port San José. The Peashooters and the Waco VPF-7s arrived there on October 10 and on that same day, they were launched in training flights aimed at familiarize the pilots with the area of operations. On the 11th, the Peashooters and the VPF-7s simulated bombing and strafing runs against the ground troops that were also part of the exercise. On the third day, October 12, the pilots were ordered to conduct close support missions, but these sorties had to be cancelled by mid-morning, right after one of the Peashooters crashed. According to witnesses, Lt. Humberto Chang, a recently graduated officer, lost control of his P-26 while trying to land and crashed on the runway, killing himself. The airplane’s fuselage was so badly twisted that it was considered a complete write-off.

Incredibly enough, the combat exercise was not called off after Lt. Chang’s accident, but as the remaining close support missions were flown, the amount of minor mishaps and near misses was such that the pilots lost their confidence and began to prejudice the P-26s even more. As a matter of fact, upon their return to La Aurora, the pilots refused to fly them whenever they had the chance and the planes were relegated to the hangars most of the time.

Back in the Capital, the revolution that toppled Ponce began near midnight on October 19th and lasted most of the next day. The rebels distributed arms to as many as 2000 civilian volunteers, the majority of them university students and workers, and attacked all the garrisons that had remained loyal to General Ponce. The city was shelled from the surrounding hills and heavy combats developed downtown, but mostly near the National Police headquarters and the National Palace. In spite of this, not a single military airplane left the ground, not in favor of the loyal troops nor for supporting the rebels. At La Aurora, the mood had been business as usual.

In the end, General Ponce resigned in the afternoon of the 20th and was allowed to leave the country with his cabinet, being followed by General Ubico hours later. A junta, composed by Lt. Colonels Francisco Arana, Jacobo Arbenz and Mr. Jorge Toriello, took power immediately and, upon assuming the control of the country, they announced that the era of dictatorships had ended in Guatemala, and offered to call for free elections in early 1945. In the meantime, the junta began a series of radical changes that included the purging of the GAAC, something that resulted in the dismissal of several pilots -including the service’s commander- leaving only a few capable hands to carry on.

Guatemalan Air Force Service

Despite the purging of the Army that followed the revolution, the coming of the new government also blew fresh air into the Aviation Corps, which was promptly reorganized under the new name of Fuerza Aérea de Guatemala (Guatemalan Air Force -GAF-) Such reorganization was reflected also in academic matters: Soon, the Military Aviation School at Los Cipresales airbase was revamped and the cadets nearing the completion of their training were sent to the U.S. for specialization courses. New equipment materialized in the form of a handful of Fairchild PT-19s for primary training, acquired under the Lend-Lease program, and -oddly enough- the transfer of the P-26s of the 4th Squadron to the School after having been replaced by five North American AT-6D armed trainers, which joined three AT-6Cs that the service had acquired June 1943.

By the end of the year, when the cadets who had been sent to the U.S. began returning, the School directorate assigned them to the training squadron equipped with the P-26s in order to keep them current by practicing combat flying. However the old Peashooters quickly demonstrated to be too much of a plane for some of them: In December 18th, 1944, Lt. Carlos Villagrán was killed when his P-26 crashed while practicing aerobatics over Los Cipresales. The cause of the accident, an investigation board determined, was the pilot’s inexperience on the type. Several near misses followed during 1945, but fortunately none of the cadets resulted injured nor any of the remaining P-26s were destroyed.

It wasn’t until February 28th, 1946, that the fourth P-26 loss occurred, once again at Los Cipresales: During take-off, the cadet at the controls aborted the run and his plane ground-looped, ending completely destroyed at the end of the runway. Fortunately, the young aviator was able to walk out unharmed.

This accident marked the withdrawal of the three surviving P-26s from the School. The planes were parked in the grass in front of Los Cipresales’ main hangar and were virtually left to rot there. However, out of sentimentalism, a couple of pilots who served as instructors at the school, took upon them the job of running up their engines every once in a while, and eventually took them out on short flights over the city during special occasions, even when the Peashooters were considered -officially- as no longer in service. It seemed that, at last, the old fighters had grabbed the hearts and minds of at least three of the pilots who, while the planes were in service, had neglected them and avoided -at all costs- to fly them. Those three kind souls were Captains Rene Sarmiento, José Luis Lemus Ramis and Pedro Granados, all of them being former members of the 4th Squadron for most of its operational life.

Curiously enough, there is a complete lack of documentation about the whereabouts and situation of the surviving P-26s from 1946 to 1953. It is assumed that the planes remained at Los Cipresales air base and that they were flown eventually, but nothing else. As a matter of fact, the next solid reference that has surfaced is a battered old photo taken in September 1953 that shows an air parade on which the three P-26s figure prominently, flying in close formation near three GAF’s C-47s and three AT-11 bombers. Coincidentally, it was around that time that the planes were pulled out of their retirement, refurbished and pushed into active service once again, this time due to the delicate political situation that the country was about to face and the closing of the Military Aviation School due to equipment obsolescence.

In Combat… Almost!

In January 1954, the U.S. Government set to overthrow the Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz, who had been deemed a Communist and a dangerous influence in the region. Thus, the Central Intelligence Agency -CIA- was ordered to launch a clandestine paramilitary operation, code-named “Project PBSuccess”, for setting a precedent in a region that was considered the U.S. backyard.

In a few words, the CIA’s plan comprised the creation of a rag-tag army, headed by a local caudillo, which would simulate an invasion to the country, while being magnified by a heavy psychological campaign launched from a clandestine radio station. Additionally, a disposable air force was to be created, composed basically by a handful of fighters and transports, in order to provide some cover to the rebel troops and for psychological warfare purposes.

By May 1954 the stage was already set: Four rebel columns would depart from neighboring Honduras and El Salvador with the objective of attack and seize several targets in the eastern region of Guatemala. Such invasion would be preceded by inflammatory radio broadcastings and leaflet-dropping and bombing raids over the Guatemalan capital performed by a couple of F-47Ns and a single P-38M that the CIA had stationed at Las Mercedes airport, in Managua, Nicaragua.

On June 4th, Arbenz’s trust in his air force suffered a disastrous blow when several sources confirmed that Colonel Rodolfo Mendoza, former commander of the Guatemalan Air Force, had escaped the country on a private plane, being accompanied by Ferdinand Schoup, the former boss of the US military mission. Both men had gone to El Salvador and then to Honduras, to join Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, an exiled Guatemalan officer who was picked up as the caudillo that the CIA needed for its rebel army.

After Mendoza’s escape, Arbenz turned his attention to the GAF aviators and discovered that it was divided. There were a considerable number of pilots who no longer supported the government and wanted to defect for joining the rebel army. As expected, Arbenz tightened the control over the fuel, armament and aircraft to the point of limiting the number of flights and forbidding any take offs without his personal authorization.

At this point it is necessary to evaluate -once again- the situation of the GAF at the time: Contrary to many reports saying that the service had grown into a formidable air arm after 1944, the air arm was still in shambles, being significant only in paper, with almost all of its aircraft grounded and the moral of its pilots virtually nonexistent. As a matter of fact the GAF leadership had been making desperate attempts to obtain additional aircraft for reequipping the service towards before the imminent aggression.

On such regard, late in 1953, Colonel Luis Girón, the GAF Commander at the time, had attempted to purchase no less than twenty two North American F-51D fighters in France without any success due to the State Department’s intervention who rushed to deny any export permits for the fighters. Something similar happened when Colonel Giron tried to purchase twenty five North American Harvards (the British version of the AT-6 Texan) in Rhodesia.

In any case, the GAF’s inventory in June 1954 included two Waco VPF-7 biplanes, seven North American AT-6 armed trainers that were considered front-line fighters, four Beechcraft AT-11 light bombers, a Beechcraft C-45 light transport, two Douglas C-47s, and a rare Cessna UC-78. Additionally, and as the situation worsened, the surviving Ryan ST-As formerly assigned to the Military Aviation School, were overhauled and reincorporated into the GAF order of battle, together with the three P-26s still on hand, even when in the great scheme of things, they didn’t make any difference.

The sorry state of the air arm is further confirmed by an intelligence report obtained by the CIA through informers infiltrated deep inside the GAF. Such document, dated early in June, said textually: “There is a complete lack of spares for the AT-11s. The planes do not have the gun-turret blisters nor machine-guns. There are enough spare parts for the rest of the planes and enough fuel, provided by ESSO. Some of the planes don’t have gun-sights and any shooting is made by raw visual calculus.” That same report adds: “The preparation for taking a flight of three planes into the air takes twenty minutes approximately. If the airport is being threatened, all the planes are taken to the North American Mission’s revetments.”

Notwithstanding these limitations, beginning on June 8th, Colonel Girón implemented a defense plan aimed to intercept and somehow “destroy” the rebel fighters that had been attacking the city virtually unopposed. Therefore, the 1st Squadron, now equipped with AT-6s, was ordered to keep at least one plane over the city at all times during the daylight hours. On the other hand, the three P-26s, piloted by Majors José Lemus, Pedro Granados and Rene Sarmiento -the same pilots that kept them alive after their retirement from the School- were ordered to patrol the outskirts of Guatemala City at the maximum possible altitude, focusing on the southern approach corridors commonly used by the rebel fighters. If the enemy airplanes were spotted, the pilots would dive towards them, at full throttle, in order to catch them by surprise, while gaining enough air-speed to make a safe escape afterwards.

Incredibly, the first patrol missions over the city were carried out without any problems and the P-26s behaved beautifully despite their age and lack of proper maintenance. However, they were unable to catch the rebel fighters, since the CIA pilots changed the ingress routes at random and attacked the Capital with surprising speed, only climb out and escape at high altitude.

By mid-July, Arbenz was out and a new “ruling junta”, more amiable to U.S. interests, had replaced him. In the process, the CIA not only had established the principles and tactics for all its future covert operations, but also had shaped the U.S. foreign policy for years to come. For those interested, the book “PBSuccess: The CIA’s covert operation to overthrow Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz June-July 1954“, by Mario Overall and Dan Hagedorn, documents in great detail the Agency’s clandestine operation and, especially, the air campaign.

Regarding the P-26s, by 1956, only two were airworthy, those being FAG-0672 and FAG-0816 (airplanes 43 and 44 in the old GAAC serialing system, respectively.) It seems that the third Peashooter, which to this day has eluded identification, was destroyed in one of the air attacks to La Aurora Airbase during the CIA clandestine operation or, according to some sources, was cannibalized in order to keep the other two flying. In any case, that same year, FAG-0672 was acquired by Planes of Fame Museum of Chino, California and the Guatemalan government donated FAG-0816 to the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum. Interestingly, both airplanes survive to this day, and the one that went to Planes of Fame is flown regularly!

Throughout the text you have “VPF-7” for the Waco type. It should be “UPF-7” — some of which were used by USAAF CPT schools as PT-14

The Waco VPF-7 (yes, with a “V”) was the export version of the UPF-7. The Guatemalan government acquired six of these in March 1937, which were delivered with a single-seat fighter configuration.

AHA! Never heard of that! I learn something new every day. Thanks for the correction!