Aviation history in general, goes back long ways in many countries. The lure of the air had been from any centuries, unreachable for most of mankind. Going as far back as the Greek Mythology, we are told that Daedalus and his son Icarus, escaped from prison, by fashioning wings and attaching them to their bodies, with wax, and when Icarus was caught in the thrill of flight, disobeying the instructions he received, flew too close to the sun, so the wax melted, and he had the first semi-officially documented structural failure, blamed on pilot error, that is, failure to adhere to “established” procedures…

So, humankind kept trying to emulate the birds, and many centuries would go by, until the discovery of the rising properties of hot gases. The Montgolfier brothers in Europe, as well as the Brazilian pioneer Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão, experimented successfully with this principle, applying it to balloons, which were more or less viable and brought men for the first time, into the realm of birds. True, activities that do not qualify like flight, always took place: Someone jumping from a cliff, committing suicide, acrobats doing their stuff, briefly left the bounds of earth; someone falling from a construction site, undertook an involuntary, one-way flight to eternity.

Fast forward to the first half of the XIX century, when “La Gaceta” in Quito, Ecuador, documents the daring ascent to over 12,000 feet performed by Mr. José María Flores. Several times his feats were completed without incident, although there was one instance when he almost landed inside the crater of the Pichincha Volcano, his non-steerable balloon, prey of the prevailing winds…

History fails to document his place of birth with absolute certainty, although mention is made of Buenos Aires, Argentina as the location where he saw the light of the day for the first time. He kept moving steadily northwards, and in Colombia, according to the newspaper “El Constitucional,” his daring exploits received the awed approval of the Colombians back when.

Mr. Flores kept traveling North, and we hear again from him when in Mérida, Yucatán –Mexico– again his hot air balloon demonstrations brought people to their feet in frank admiration. Twice he went up in San Luis Potosí, and twice he managed to return safely to mother earth. By the end of 1847, the experienced Flores had already made more than 60 successful ballooning ascents in other countries, including Venezuela, Colombia and the already mentioned in Mexico. At that point, he was reputed to have floated higher than any other balloonist in the world, with the exception of the international champion, Gay-Lússac.

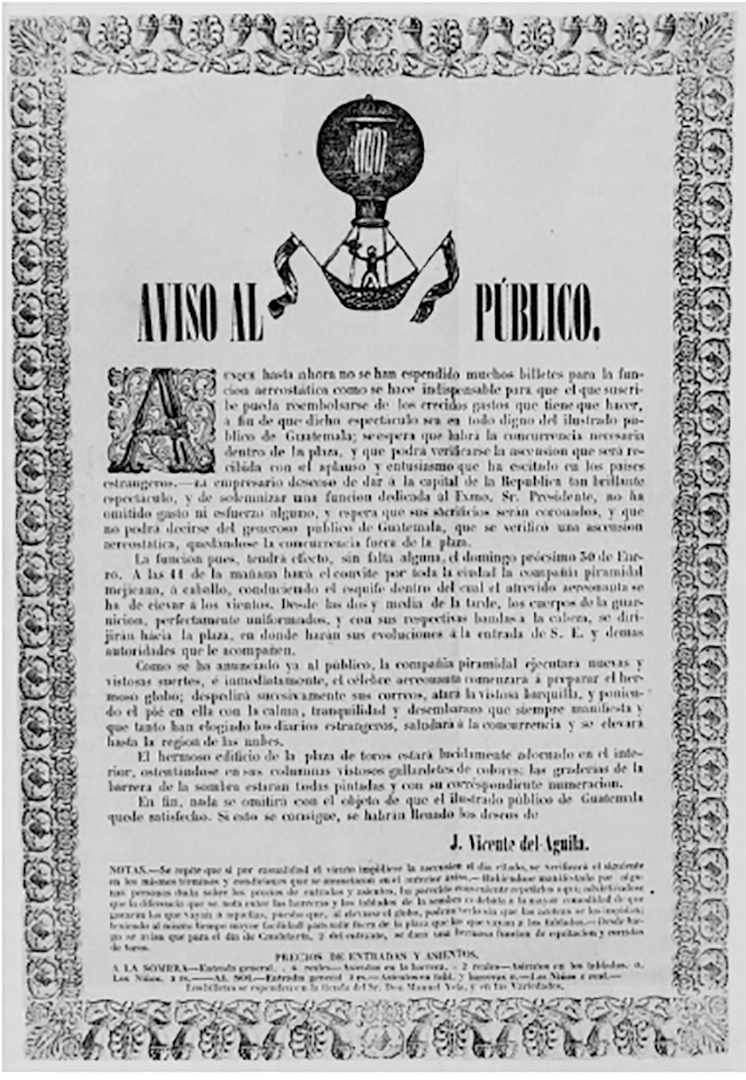

On Sunday January 31, 1848 the temperature was pleasant, as it usually is in Guatemala, and the skies were clear, while winds were negligible, according to “El Libro de las Efemérides” (The Book of Anniversaries.) The atmosphere was charged with anticipation, and the inhabitants of the Valley of La Ermita, where Guatemala City is located, were all looking forward to the announced hot air balloon ascent, and many a pious person, made the sign of the cross in disbelief of what was going on with the world, while at the same time silently praying for the well-being of the brave adventurer. It is understandably then, that the prospect of actually seeing a fellow human being escape the bonds of earth, defying gravity, thrilled “Chapines” (as the Guatemalans call themselves colloquially) to no end, since it was not something that happened every day, and besides, Chapines are famous for being “noveleros” (that is, easily awed by new and interesting events.)

Tradition dictated that when any event of importance was to take place in Guatemala, the “Convite” (that is, like an invitational parade) would go through the main thoroughfares of the capital, so the people would know what was about to happen – as if they didn’t already know!

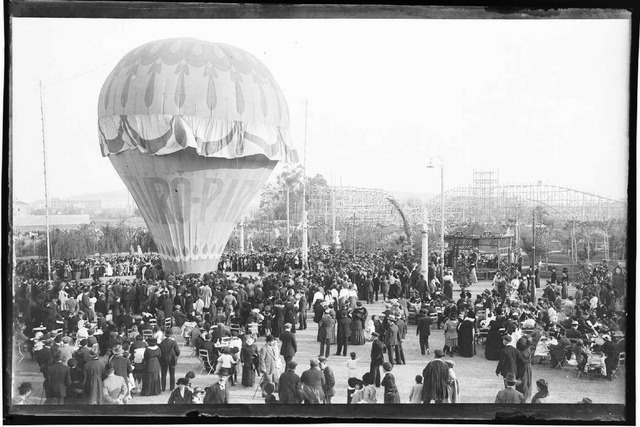

Coming noon, the crowds headed towards the Plaza de Toros (Bull fighting Arena), where the aeronaut would perform his daring feat, and where the balloon would be set up, and hot air would expand its envelope to make it rise through the skies of our beautiful Guatemala. The Plaza de Toros was then, in the outskirts of the city, where nowadays, the Plazuela Barrios and the railroad station are, that is, the commercial center of modern Guatemala City.

Those wealthy enough to own or to afford to rent a carriage, did so, most everyone else, walked. Accommodations were sparse beyond the limited seating provided at La Plaza de Toros, so the neighboring hillsides, trees and any vantage point, were crowded with thrill-seeking chapines (or, noveleros, as we mentioned earlier), decked in their Sunday’s best clothing.

Music filled the air, played by military bands; the main seating section at the plaza, having been brightly decked out for the occasion, was soon enough occupied by the President, Rafael Carrera (a.k.a. Racarrarraca), accompanied by the vice-president (whose name the newspaper report did not record, but keeping with the unspoken international tradition for vice-presidents, should remain anonymous…) as well as other civilian and military representatives.

Filling up the balloon, of about 40 in diameter by 60 feet in height, was taking too long, so in order to keep the President and his guests amused, a Mexican horse troop maneuvered in the plaza, to the music provided by a military band, and when they were done, a group of minstrels demonstrated their acrobatic abilities. Two small paper globes were released, as a means of placating those who could not make it inside the plaza, what was to come, since they had been craning their necks up for a long period of time, and nothing was happening thus far.

When it was around five-thirty in the afternoon, Mr. Juan Flores finally showed up at the center of the plaza, and after bowing to those in the balcony, climbed into the balloon’s basket. He removed his hat with a flourish and threw it upwards, while at the same time proceeded to move the hair away from his forehead, and indicated to those in his assistance, that he was ready to go.

The ties that bound the balloon to mother earth were severed, and faster than a stuttering rooster cock-a-doodle-doo, rose up in the atmosphere. Everyone present was astounded, but suddenly their awe became terror… Upon reaching 900 feet or so, on the side of the balloon, a flicker of a flame appeared… And soon enough, the whole envelope was engulfed in flames. Everyone witnessed in mute suspense, the futile efforts by Mr. Flores to put out the flames. For three minutes he struggled, until all of a sudden, the basket detached from the balloon and fell with ever increasing speed, until it hit the ground.

The first people to make it to the scene of the crash saw Don Juan’s broken body, to be taken immediately by the soldiers to the San Juan de Dios Hospital, located close by. Unfortunately, Mr. Flores passed away minutes later, while still on his way to the medical facility.

Even the bravest of the brave present that tragic afternoon, felt fear and pain in their hearts; maidens fainted right and left, while older women went on and on, criticizing men in general, for taking such ridiculous risks with their lives, while at the same time were defying all that was sacred and holy, trying to fly, something only reserved for the angels.

Probably the most disconsolate individual was the promoter of the ill-fated exhibition, José Vicente del Águila. On February 6, 1848, one week after the accident, del Águila organized a public display of the finest bulls and horses from the best Guatemalan haciendas, which was given at the Plaza de Toros; the entire proceeds from this sad benefit were donated to the widow and children of José María Flores, who had stayed at Oaxaca, Mexico, in order to economize on travel expenses.

Had Juan Flores been successful in his endeavors, his name would be famous and not only a footnote on our history books. His story however, still reaches us to us to this day, showing that all advances achieved by humans are stepped in the blood and bodies of those precursors, the pioneers, those who dare, who sometimes fail, but more often than not, with their valiant deeds, point the way to the future for the rest of us.

Documentary Sources

– Sección Artes y Letras. Diario Impacto, Guatemala. Sunday, July 27, 1969.

– The Death of Flores. The Princeton University Library Chronicle, Autumn 1982, Vol. 44, No. 1. Retrieved from JSTOR.

The materials used to prepare this short feature, were provided by Dr. Gary Kuhn, to whom my sincere thanks go for his help and support. You’re one of a kind, Tio Gary!!!

This article was first published in April 2001.