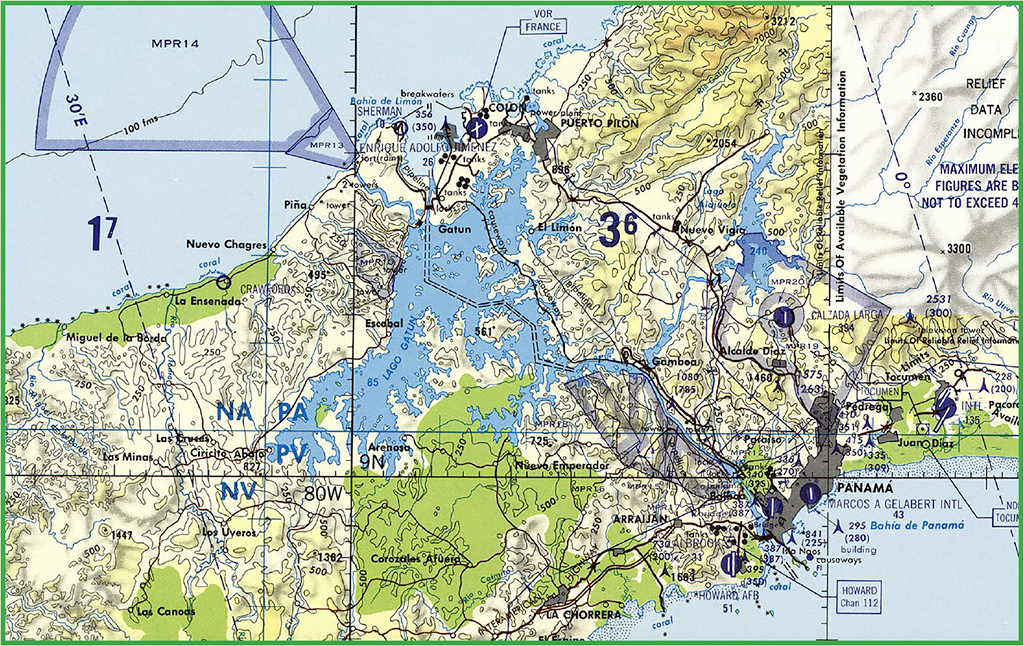

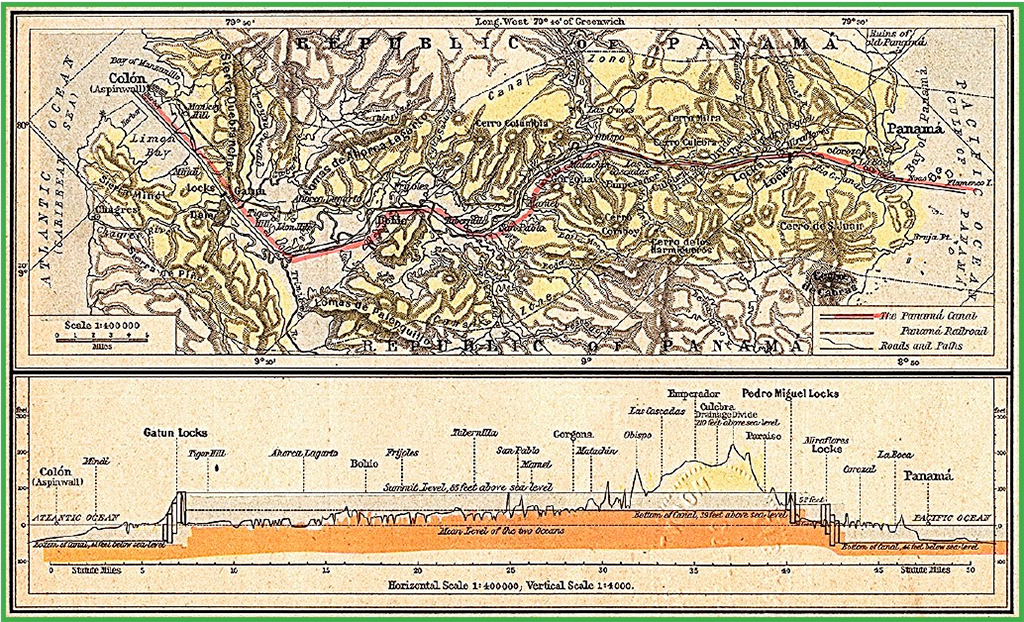

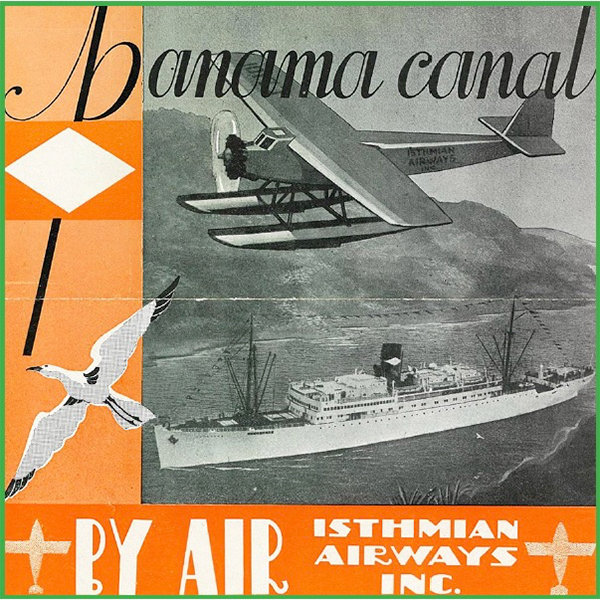

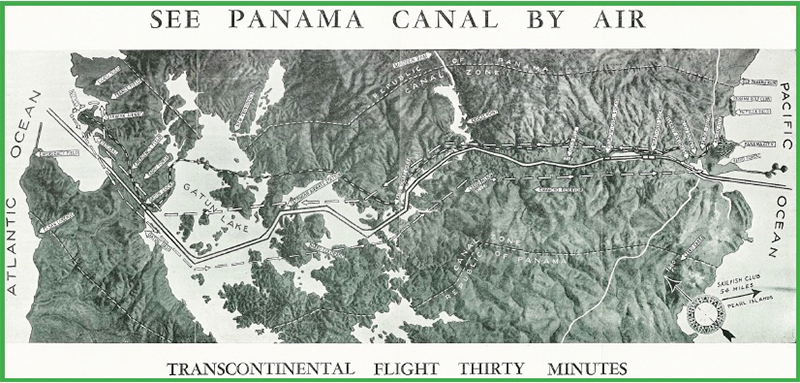

The April 1930, edition of the Bulletin of the Pan American Union noted that: “The shortest air line in Latin America, and possibly in the world, is that of the Isthmian Airways (Inc.). Passengers and goods are carried 47 miles from ocean to ocean over the Panama Canal several times a day.”

It was, indeed, a short route offering regular service back and forth across the Isthmus of Panama, all the while staying primarily within the boundaries of the Canal Zone (C.Z.). Isthmian Airways was founded in 1929.

Who came up with the idea of trans-isthmian service in the first place, however, is up for discussion. One hint was a short story in the January 1924 issue of Aeronautical Digest, in which the magazine’s “France Field Correspondent” reported that a few of months earlier, on 15 October 1923, “France Field-Balboa Transcontinental Aerial Mail Service” had begun. The correspondent noted: “A plane takes off each day from France Field with the official mail for Department Headquarters, lands at Balboa Field, delivers the Headquarters mail and picks up the mail for France Field.” Although the reporter does not so state, it is reasonably to assume that the service was operated by military aviators. It is also not certain how long this service was operated.

In the late 1920s, there were actually two civilian companies flying nearly the same route, and again it is subject to an exchange of views on who first came up with the idea. It could have been Juan Trippe, or someone else in the nascent Pan American Airways (PAA) company, who saw the exclusive operating rights in, and through, the C.Z. as an important measure to keep other competitors out of the area. After all, back in that time there were basically two routes down south from the United States to connect to the lucrative South American air mail, and later passenger, markets. One route was towards the east, from southern Florida, through Cuba, then south along the Greater and Lesser Antilles working on controlling this route, and within a year or so, they would. The other path to South America was out west, down through Mexico, thence Central America, with a sort of choke point found in Panama. PAA was planning, as one correspondent of the day surmised, to make Panama the “air center of a great network of routes for air mail, passengers and express service between North and South America, and the West Indies.” Although often flying seaplanes or amphibians, what with the aircraft development of the day, it was still seen as prudent to choose routes that were near land. With advances in aircraft technology, this caution, of course, would be dismissed within a few years. More importantly, with the international shipping passing through the Panama Canal, the C.Z. was seen as a part of a profitable air mail market, which more so than passengers, was earning cash, and government subsidies, to pay the bills. So, as with any other market that PAA entered, it was important to keep an interloping airline, whether foreign or domestic, out of the area. History shows that Juan Trippe could be quite ruthless when it came to keeping competition at bay.

On the other hand, perhaps the idea was conceived by a civil engineer named Ralph E. Sexton, later a pilot himself, but was at the time sufficiently aviation-minded to see a good opportunity when it presented itself. Sexton was born in 1885, in Bushnell, Illinois. As a young man he attended the University of Illinois, and later Stanford University, ultimately graduating from Cornell University in 1907. After a time working for the city engineering department in Enid, Oklahoma, on 24 November 1910, Sexton reported for work down in the C.Z., initially employed as a draftsman, in the Division of the Chief Engineer. In September 1911, he began working for a firm called the American Bridge Company, although it is not certain what projects were awarded to the company. At some point Sexton apparently left that company, and teamed up with another engineer by the name of Harry A. Pearce to form a company called Pearce and Sexton, still working as a contracting engineers in the C.Z.

After the completion of the canal, on 30 October 1915, Sexton, and presumably Pearce, terminated their business with the C.Z., and moved their company further south. In 1918, they were noted as doing contract engineering work in Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Peru. While not clear exactly when, at some point, Sexton went to work for a company called the Chicago Bridge and Iron Works, a firm that was working a number of contracts in South America. Sexton was in Colombia in September of 1925, where documents show he married his second wife. It was sometime during his life in Colombia that Sexton met a wayfaring aviator by the name of Jack Miller.

Born in 1898, in the small town of Rulo, Nebraska, John H. Miller was a farm boy who would go on to live an aviator’s life that is the stuff of adventure novels. “Jack” Miller had just started going to school at the Peru State Normal Teachers College (Nebraska) when it appeared the United States would enter World War One. Fibbing about his age – he had to add a year to make him eligible to join – he enlisted in the U.S. Navy, and trained as an Aviation Machinist’s Mate, quickly advancing to the point that he was instructing new machinist mates in the skill. In 1920, Miller headed south for flight training at Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola, Florida. The war was over by the time he pinned on his Wings of Gold, so he was sent up to NAS Great Lakes, Michigan to instruct on flying boats.

Miller left the active duty Navy in the early 1920s, and while still in the Naval Reserve, started a free-for-all life in the air, a life lived by many former military aviators while the aviation world around them was still evolving. For the next few years he barnstormed around the county, flew numerous air shows, and competed in various air races. In 1923, he was appointed as the chief flight instructor at the Chicago Aeronautical Service, where he penned several books on the theory of flying. It was in the mid-1920s, that Miller also became acquainted with Lieutenant Richard Byrd, who was then heavily involved in planning his 1926 North Pole flight attempt. Miller was invited to join the crew, but turned the offer down, later stating: “At the time I didn’t think I’d missed anything. It was cold enough for me right there at Great Lakes.”

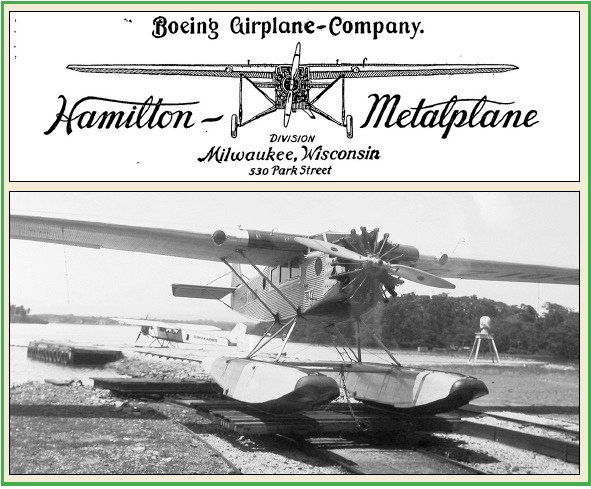

By around late 1925, Miller had signed on with the Hamilton Metalplane Company (more on the Metalplane below) as a test and demonstration pilot, as well as a delivery pilot. He competed in several local and national aerial competitions, winning a trophy or two, and flew a number of exhibitions hops from the cockpit of a Metalplane. Miller made the news in July 1928, when he was noted as taking a Metalplane, this one on floats, up to an altitude of 13,000 feet, in a test to prove the aircraft could top some, but of course not all, of the mountain peaks in South America.

In September 1928, Miller delivered the first of two Metalplanes that would be operated by the Andean National Corporation, at Cartagena, Colombia. Andean National was a Canadian oil company, later to be an affiliate of Standard Oil, building a pipeline that ran generally along the Magdalena River, from the oil fields of the interior of the county to the port at Cartagena. Prior to the company’s introduction of aircraft, the fastest form of transportation in support of its operations was via riverboat, still a maddeningly slow prospect. In order to speed up communications, Andean National began flying a couple of Sikorsky aircraft – an S-32 on floats, and an S-36 amphibian, both of which were suffering from the humid tropical climate. Company officials viewed the all-metal Hamilton Metalplane as a perfect replacement.

As related by C.A. Blanchard, in an 11 May 1928, newspaper article (The Akron – Ohio – Beacon Journal): “Only Jungle Paths – Unless one makes the trips by air from Cartagena to the oil fields, 400 miles in the interior, there are only the treacherous jungle paths and the Magdalena River by which to travel. “The jungle paths mean weeks of travel with the temperatures around 100 degrees and the river steamer makes the trip in six to 10 days. But over the tropical region, above sparsely settled areas, planes fly from the coast to the oil fields in three to four hours.” Mr. Blanchard, noted as the Chief Mechanic of Andean National, was at the time, at the Hamilton Metalplane factory in Milwaukee, Wisconsin awaiting the delivery of the company’s “new cabin monoplane.”

When Miller arrived in September he met the manager, and indeed the only pilot, of the Andean National flight department, a Russian emigre by the name of Boris Sergievsky. After a few orientation flights, Sergievsky departed Colombia on a long-delayed vacation, leaving Miller to do the flying. Once in the U.S. Sergievsky worked for a time for Hamilton Metalplane, as a test pilot, before his bosses at Andean National tasked him to head to the Sikorsky plant at College Point, New York, to supervise the construction of the company’s new Sikorsky S-38B amphibian. Ultimately, Sergievsky would quit Andean National and go to work full time for Igor Sikorsky.

As for Jack Miller, he stayed in Colombia several months to supervise the assembly of an additional aircraft, presumably the second Hamilton Metalplane, as well as checking out pilots on a route that traced the company’s pipeline along the Magdalena River. It was around this time frame, although the exact date and circumstance is obscure, that he met Ralph Sexton.

Again, the actual details of the genesis of Isthmian Airways are somewhat murky. Most references give credit to Ralph Sexton, while several others state that there was a partnership established with Sexton and Jack Miller, however equal that may have been. Miller is also often mentioned as the company’s chief pilot, and indeed the company’s only full-time pilot for much of its early history. Another reference has it that Miller and Sexton met in Panama, while Miller was en route with the first Hamilton Metalplane destined for Colombia, and it was here that the idea for Isthmian Airways was hatched. Regardless, U.S. Department of State records indicate that as early as the summer of 1928, Sexton was petitioning the U.S. Government for permission to start his airline. Sexton also applied to the governor of the C.Z. for permission to operate wholly within the C.Z., which was later approved. A one-time fee to fly within the C.Z. was put at $25,000. Additionally, a small yearly fee was required to keep his operating license in effect. Sexton concurrently applied to the Republic of Panama for permission to operate to points within the Republic, outside the C.Z., which was also later approved.

The process of granting permission for any of these operations was painfully slow, and one can imagine the consternation felt by Sexton. Several U.S. government departments – State, War, Navy, Commerce, Treasury, etc… – had a hand in the decision making process, and each could render an opinion – either yea or nay – in the matter. Finally, on 24 April 1929, Sexton was informed by the Department of State that permission was granted to operate an airline within the C.Z. Around this time, permission for flights from the C.Z. to points with the Republic of Panama was also granted.

As noted, Sexton applied for a concession from the U.S. Department of State to operate an airline from the Atlantic side of the C.Z. to the Republic of Colombia. Correspondence at the Department of State indicates that State was inclined to approve this service. If granted, this would put Isthmian Airways in direct competition with PAA, as well as with a well established Colombian airline called La Sociedad Colombo-Alemana de Transportes Aéreos (SCADTA). Both PAA and SCADTA were jockeying for the rights to operated flights out of Panama to points further south. By October 1928, the Department of State informed Sexton that his application to operate from Panama to Colombia was still under review. The reason for the delay is not clear, and by June 1929, Sexton was still pestering the Department of State for a decision, however, authorization for flights to foreign countries – i.e. Colombia – was still under review and was pending.

Meanwhile, Isthmian Airways, Inc was noted as a newly established Delaware corporation on 8 March 1929, with a capitalization of some $500,000, which if accurate was not an inconsiderable sum of money, even today. Although a list of the other stockholders is not readily available, it appears that a number of businessmen based in the C.Z. were proponents of the idea, as well as investors.

Briefly, during this time the C.Z. was administered by the United States, with a civilian administration headed by a governor, who was appointed by, and was under the supervision of, the Department of War. Funding for the administration of the C.Z. came from the U.S. Army Appropriation Bill. The U.S. Department of State was also involved in running the C.Z. As mentioned in the 9 March 1929 issue of Aviation magazine, the State Department promulgated a series of aviation regulations concerning access to the airspace in the C.Z., the most important of which was prohibition of foreign aircraft flying solely within the C.Z. Foreign aircraft could still, with prior permission from the Department of State, fly in and out of the C.Z., but not between two points totally within the C.Z. Another part of the new regulations was the requirement that all U.S. operated aircraft be made immediately available to the military in the event of war. Of course, outside the C.Z. the airspace was controlled by the Republic of Panama, which although it was an independent country, was heavily influenced by U.S. interests.

That Isthmian Airways would go head to head against PAA was clear to even the casual observer.. In a short interview that appeared in the 21 April 1929, issue of The Panama American newspaper, Sexton was asked how PAA’s plans for the route would affect Isthmian Airways own plans, to which he replied: “In no way whatsoever.” Rather slyly, Sexton stated: “In fact, your information is the first we have heard regarding the plans of Pan American Airways to operated planes across the Isthmus.” He went on to tell the reporter that the “Hamilton convertible seaplane” had been delivered, and was now fully assembled, that hangars, with “runways” leading down to the water, on each end of the route had been built, then summing up by saying: “Only a few details and technicalities remain to be cleared up.”

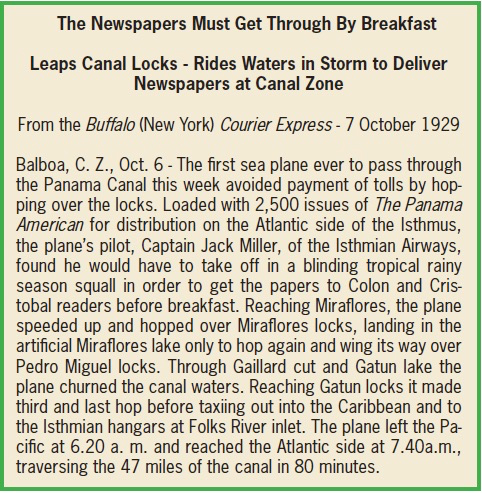

Preparing for revenue service, on 30 April 1929, Sexton dispatched Jack Miller, in the company’s sole Metalplane, on a proving flight. Departing in the morning, this test flight was a round trip from Cristobal to Balboa, and back. Sexton went along as the sole passenger. The flight returned to Cristobal that afternoon and was noted as without incident. Isthmian Airways was ready to commence service.

On 1 May 1929, PAA beat Isthmian Airways off the mark to be the first to operate regular trans-C.Z. air service, using a six passenger Fairchild Model 71 monoplane. The two terminals used were France Field (Cristobal) on the Caribbean side (sometimes referred to as the Atlantic side), and Albrook Field (Panama City) on the Pacific side. Both were military air fields, so some negotiation with the Department of War was clearly required. The frequency was reported as three times a day. In all the many volumes written on the history of PAA, this little run of less than 50 air miles, gets scant, if any, mention. It was, however, sort of a hidden part of the far-ranging air mail route called Foreign Air Mail (F.A.M.) 5, a multifaceted run which began in Miami, Florida, (after PAA had moved up from Key West) making literally dozens of stops before reaching the C.Z., and then continuing to parts south. Within these stops on F.A.M. 5 was a leg listed as: “Panama City, Panama to Cristobal, and Return.” Although PAA certainly had the monopoly on the ever important air mail contract, at least for the time, there was always a chance of losing it in the future. Keeping other airlines out of the arena was important.

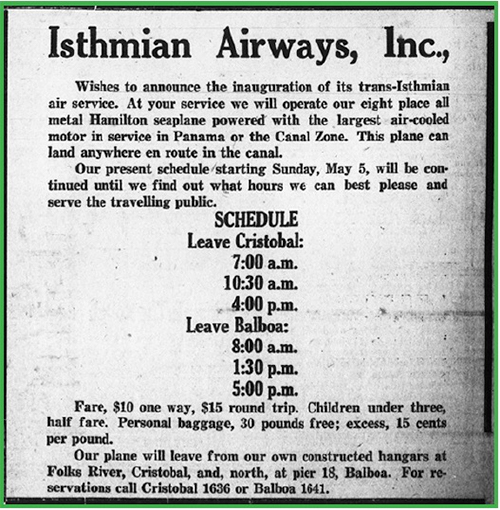

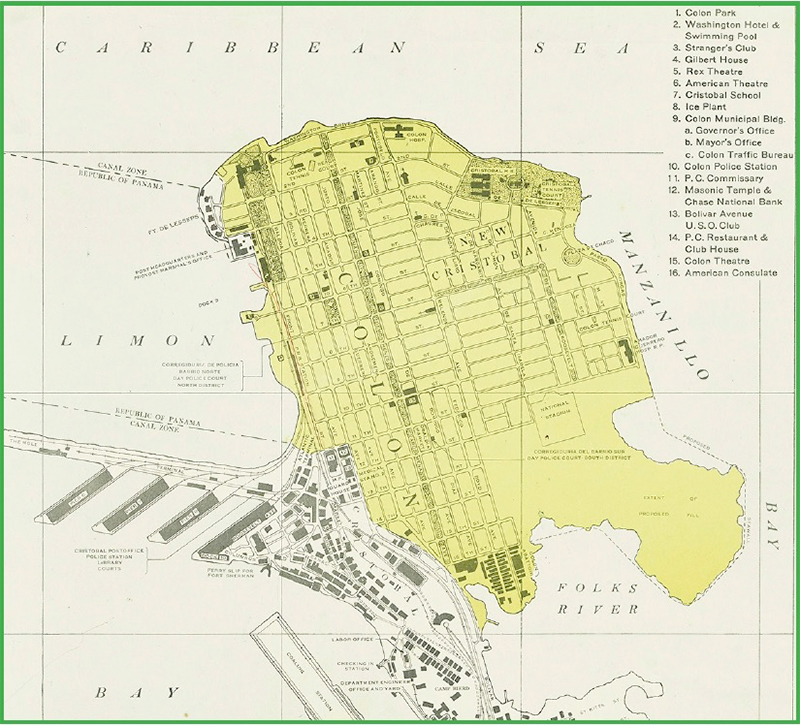

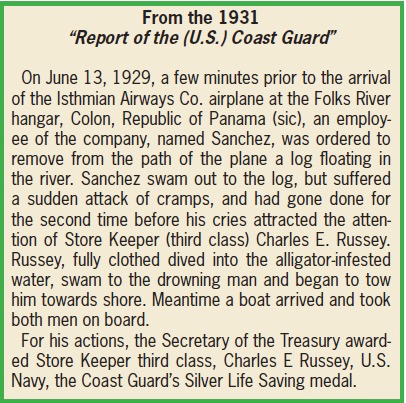

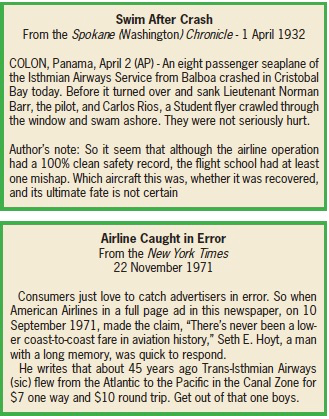

It was on 5 May 1929, that Isthmian Airways got underway, with Jack Miller, as pilot, flying the only Hamilton Metalplane of the fleet, on the airline’s first run from the waters of the Folks River, at Cristobal, on the Caribbean side to a landing in the inner harbor at Balboa, on the Pacific side. One-way distance was 47 statute miles. Planned frequency was to be three round trips daily – in the morning departing Cristobal at 7:00am and 10:00am, and then in the afternoon at 4:00pm. Return flights departing Pier 18 at Balboa at 8:00am, 1:30pm and 5:00pm. It was noted that the schedule could be modified depending on the loads. Fares were $10 one-way, and $15 round trip, with children under 3 years at half price, and up to 30 pounds of baggage per passenger at no charge – 15 cents a pound thereafter. These rates were later reduced somewhat, with the onset of the Depression. Hangar and passenger facilities were built at both bases.

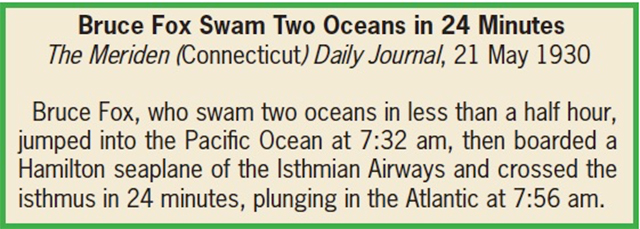

From its inaugural flight on 5 May, to the 26th of July, Isthmian Airways carried some 1,500 passengers on its “transcontinental” route. Although the numbers vary with the source, from 5 May 1929 to 5 May 1930, Isthmian Airways carried around 9,000 passengers. Sightseeing flights could also be arranged on demand. One popular itinerary was for a party to hop on a ship at one end of the canal, and enjoy the slow ride through the locks, and then across the isthmus, through the numerous Reaches (Pariso Reach, Cucarache Reach, Las Cascadas Reach, etc…) of the canal, and via Lake Gatun. At the other end of the canal, the party would hop on an Isthmian Airways aircraft for a dedicated, one hour, scenic flight back to the other end. Short side trips along the coast could also be added on. Fare for this service was $12.50 per person, based on a party of at least six people.

Another option for ship passengers was to depart their ship as it entered the lock, fly to the other end of the canal – either end, to Cristobal or Balboa – and spend the day there. As noted in the July 1930, issue of Aero Digest: “The time saved gives them ample opportunity to stretch their legs in long walks by the ruins of ancient Panama City or to investigate the offerings of the numerous oriental bazaars which cluster in the narrow streets of Colon.”

Isthmian Airways was planning to, and eventually did, found a local flying school. Regarding this school, the 5 October 1929, issue of Aviation ran an article noting that the Travel Air company, out of Wichita, Kansas, had just shipped a three-seat, Wright J-5-powered Travel Air E-4000 biplane down to Isthmian Airways. To be equipped with floats, the aircraft was to be used for flight instruction. Further, an article in the September 1929 issue of Aero Digest relates that the pontoon-equipped Travel Air was to be used for primary flight training, after which a student would move up to a Hamilton Metalplane for the advance course. More about this school below. Rather ominously for the folks over at PAA, in the 8 May 1929 issue of The Panama Canal Record, Isthmian Airways was also noted as planning to start an air service much further a field, into parts of the Republic of Panama, outside the C.Z., and that more airplanes were on the way to provide this service. One correspondent reported, as early as 16 March 1929 (in The Panama American), that: “The trans-Isthmian air-line which he [Sexton] proposes to establish is thought to be only the fore-runner of an extensive network of air-lines throughout Panama.” Later reports mentioned flying down in to Colombia and beyond.

For the next several years, the pilots at Isthmian Airways settled down in to regular trans-isthmian service, carrying thousands of passengers, all with an enviable safety record. It should be pointed out the Isthmian Airways did not have a Foreign Air Mail contract with the U.S. Post Office, so the major portion of their revenue came from these passengers. Many of them were tourists, tempted off their ocean liners for a quick aerial tour of the canal, thence to meet back up with their ship as it came out of the locks. There were also a modicum paperwork and documents, as well as sailors that needed to get from one end of the canal to the other. Although the airline did not haul a large amount of cargo, they did carry some items, such a daily newspapers, on a regular basis. It was noted that an American newspaper (The Panama America) printed in Panama City could be on sale in Cristobal in the morning, about the same time a competing newspaper was still being loaded on the train back in Panama City. Another service that was offered for a time was a buying and delivery service, of sorts. For example, a person in Cristobal could order a product from Balboa, and have it delivered a short time later, by air. Still, it was people, often tourists and sightseers, who paid the bills. Speaking of which, the $10 one-way airfare in 1929 would equal around $180, give or take, in today’s money.

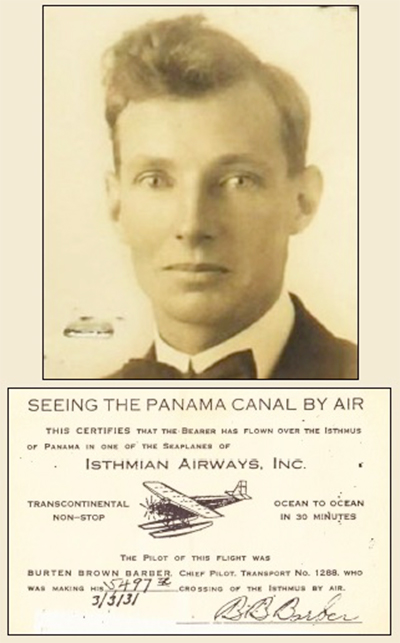

Isthmian Airways, additionally, was available to fly special charters almost anywhere with in the range of their aircraft. As early as July 1929, Miller piloted a flight taking a Mr. William A. Stevenson, of Ancon, down to Barranquilla, Colombia. Another example, later in October 1933, the airline made a deal with the British Cunard Line to fly passengers from a Cunard liner, then transiting the canal, out to Isleta Trapiche (Trapiche Island), some 50 miles southeast of the Pacific exit of the canal, in the Archipiélago de las Perlas (Pearl Islands Group), for a few hours of sailfishing. How many of these trips were completed is not known. Speaking of sailfishing among the Archipiélago de las Perlas, in May 1932, a group of reasonably affluent local fishermen formed a group called the Pacific Sailfish Club, who soon deciding they needed to build a clubhouse close to their favorite fishing waters. In 1933, they built their clubhouse out on Trapiche Island. To get there by boat took several hours, so it was natural to charter Isthmian Airways to fly the club members on a quick flight out to the island. Again, how long this service was operated is not all that clear. One of Isthmians Airways’ longest tenured pilots, Burton Barber, recalled in a later newspaper article how he enjoyed the: “thrill of landing his Hamilton or Beechcraft seaplane on some small rivers in the midst of the Panamanian jungles while transporting gold miners to or from the gold mines.”

In the 26 October 1929, issue of Aviation magazine, the correspondent Frank Haynes noted that: “This speedy service, plus the willingness to oblige at all times, has endured the operators [Isthmian Airways] of the service to residents of Panama and the Canal Zone, and has assured for it a profitable future.” And, for several years the future did, indeed, look good. In the Spring of 1935, things for the people at Isthmian Airways took a turn for the worse. On 12 March, it was reported that the airline had shut down. The reason given in the news accounts was rather vague, simply stating that the company’s operating license, issued by the C.Z. authorities, had expired. This was not entirely correct, as the license had not expired, per se, but had been revoked. The authority in this case was Governor Julian L. Schley, a former Chief of Engineers in the U.S. Army, and an appointee to the governorship by the Department of War. One newspaper report recorded that the stockholders in the company were petitioning for a receiver to be appointed, which may or may not have been true. Outside of these stockholders, however, local businessmen and representatives from several steamship lines, more than just your average tourist, cried foul and pleaded with Schley to reinstate Isthmian Airways licenses. This, in fact was done, and in that same month of March 1935, the airline was back in operation. It was not to last long, as on 30 June 1936, Isthmian Airway’s operating license was again revoked, this time for good. The company ceased operation. Again, the numbers vary by the source, but a conservative estimate is that Isthmian Airways carried over 50,000 – some say the number is closer to 65,000 – passengers. Of course, PAA, in the form of its subsidiary Panama Airways, took over the business, beginTri-Motors between Albrook Field and France Field. PAA later wrapped up the Panama Airways operation on 30 April 1941.

So, what happened to bring about the sudden demise of Isthmian Airways? While it is not readily available as to exactly what Ralph Sexton’s reactions were to all of this, he was angry enough to, at least once, bring suit against the U.S. government for his losses. The abbreviated transcript of the court case provides a some answers, but ultimately leaves more questions. It should be pointed out that this particular court case was not an effort by Sexton to resume operations, but rather to recover some of the money he lost when he was unfairly, at least to him, shut down.

According to the information presented in court by Sexton and his lawyers, on 7 March 1929, then C.Z. Governor Harry Burgess issued to Isthmian Airways two licenses – one which permitted the company the use of plots of land and sections of water on which to operate, while the second allowed Sexton to build hangars, buildings, and make other improvements on the aforementioned plots of land. These licenses had no expiration date, as long as a license fee of $100 was paid each year. A third license, later issued by Burgess, was permission to operate the air service within C.Z. airspace, which also had no real expiration date, as long as the fee was paid on time. With these licenses in hand Sexton spent in excess of $30,000 on improvements to the land, as well as the building of hangars, shops and passenger facilities.

Everything was going along quite well until late 1934, when C.Z. Governor Julian Schley, who had taken over from Burgess on 21 October 1932, began to make life difficult for Isthmian Airways. Sexton contends that Schley, and his staff assistants, began to pester the company by making arbitrary, predatory, and wholly unnecessary demands on the airline. In a letter dated 11 February 1935, Governor Schley charged Sexton and his airline with: “Incompetent management, failure to maintain equipment properly, failure to maintain proper records, failure to establish a system of replacement of obsolescent airplanes, failure to carry adequate supplies and spare parts, insisting on unsound practices contrary to exert advice, and removal of manufacturer’s data and identification plates from aircraft.” That was quite a list, and it is not certain where Schley got his information. Of course, Sexton vehemently countered stating that: “these charges were made in bad faith and were false and without justification.” Regardless of Sexton’s protestations, Isthmian Airways was shut down in early March 1935.

After a number of conferences between Sexton and the Schley, and members of Schley’s staff, an agreement was reached, which allowed Isthmian Airways to resume operations. The term of this new authorization ran from 16 March to 31 December 1935, and although Sexton agreed to the stipulations of the deal, he found it very difficult to comply. Within the agreement was a requirement to procure new aircraft, purchase at least ten newly overhaul engines, and to refit the Metalplanes still in use with new wings. Also, and perhaps most onerous was the requirement that beginning 1 January 1936, all of the Hamilton Metalplanes had to be either retired, or completely overhauled, with a completion date of no later than 1 July 1936. While Isthmian Airways was back in business, Sexton continued to protest many of the stipulations set forth by the C.Z. government, but to no avail. Governor Schley revoked Isthmian Airways operating license on 30 June 1936, and the airline closed down the next day. Then, on 2 July, Sexton received a letter from Schley stating that since Isthmian Airways no longer had a license to fly, all of the other licenses were also revoked. Sexton was given until 1 October 1936, to remove all of the buildings, and other improvements, situated on the government’s land.

In court Sexton claimed that most of the stipulations, especially the one about retiring, or rebuilding, all of the Metalplanes, were arbitrary and unreasonable. He stated that the Metalplanes were fully airworthy and were in no need of a “complete major overhaul.” He also noted that the other airline operating trans-isthmian service – presumably PAA, but he did not mention them by name – had a much older fleet of aircraft. Sexton reminded the court that until the time that Schley began to impose his will on the airline, Isthmian Airways had maintained a near perfect schedule, and had never had an accident, nor injured a passenger. By the time this particular court case was concluded – years later on 3 November 1941 – Isthmian Airways was a thing of the past. Sexton’s claims for some $225,000 in damages was denied, and the case dismissed.

Again, it should be pointed out that this particular court case was not to determine whether or not Schley was wrong in shutting down Isthmian Airways. Rather, it was held to determine if the government can be held financially liable for illegally, and without merit, shutting down a business. To Sexton, the fact that Schley was wrong was without question, and this suit was to simply recover some of the money he had invested in Isthmian Airways.

The big mystery here is why Governor Schley suddenly, and seemingly without much forethought, decided to shut Isthmian Airways down. His list of grievances against the airline was quite extensive, and certainly severe. At no other time did Isthmian Airways fall under such scrutiny. Even Schley appears to have been satisfied with the airline, at least the first 15 months of his governorship. As mentioned above, Isthmian Airways’ safety record was exemplary, and the Hamilton Metalplane, more so than many wood and fabric airplanes of the day, was certainly suitable for the hot, humid conditions of the C.Z. And, the airplanes were not even that old. At least one observer of the case posited that it could have been behind the scenes machinations of PAA to rid the C.Z. of competition. Perhaps PAA was nervous that Isthmian Airways would, as Sexton predicted, expand outside the C.Z., thus threatening PAA’s hold on the market. This theory is, of course, pure speculation. Perhaps, the aircraft were not in that good of shape, as related later in this article. Maybe, in the back of some dusty archive, there is a file containing the reasons why Schley went after Isthmian Airways like he did. Until that file is found, we can only guess. On 18 January 1945, Isthmian Airways’ Delaware incorporation was repealed.

Isthmian Airways’ Pilot Roster

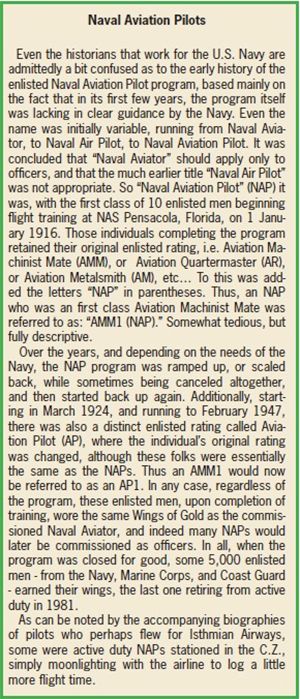

Unless there is an extant source record, perhaps tucked away in that dusty archival file somewhere in Panama, it is difficult to say exactly who was on the pilot roster at Isthmian Airways. One reference posits that many of the pilots who flew for the airline were U.S. Naval Aviators or U.S. Army Aviators stationed there in the C.Z., and who flew on an ad hoc basis. If so, there seems to be no documents which lists these aviators (again where is that dusty file?). However, by examining the biographies of some of the pilots, this moonlighting supposition appears to be true. Another reference states that there was only two, full time civilian pilots who flew for the company. In its short existence, Isthmian Airways had upwards of eight aircraft, flying the trans-isthmian route, various charters, as well as equipping the flight school. Considering this fleet, there must have been a reasonably sized pilot group.

So, presented here, in no particular order, is a best guess, based on various documents, magazine articles, newspaper accounts, and forum chats, as to the pilots who flew for Isthmian Airways.

Ralph Ernest Sexton (1885, Bushnell, Illinois – 1956, Panama City, Panama): A trained civil engineer by trade, he learned how to fly in his own flight school, presumably by Jack Miller, and in his own Travel Air biplane on floats. Although no documentation stating this has been unearthed, there is one ephemeral mention in a newspaper article (La Prensa, 2006) that Sexton was, in fact, a licensed pilot.

John Henry Miller (1898, Rulo, Nebraska – 1980, Orlando, Florida): As chronicled above, Captain “Jack” Miller had done a lot of flying before he became associated with Isthmian Airways. Leaving the company that he had helped get off the ground, on 1 August 1931, he signed on as a pilot with Pan American-Grace Airways (PANAGRA, formed on 25 January 1929), flying for that company until his retirement in 1951. Having started with PANAGRA flying the Sikorsky S-38 amphibian, he retired on the Douglas DC-6, and was at the time the highest time pilot for the company. After living in Panama, Colombia, and finally Lima, Peru for all those years, in retirement he moved with his wife up to Orlando, Florida, where he started another career in the lucrative Florida real estate business.

Miller amassed over 25,000 hours in the air, without any serious incidents. He did have one reported rather hair-raising incident while flying the President of Colombia on a secret flight between Peru and Colombia. Details are scarce, but apparently the airplane (type ?) was sabotaged, causing one of the propellers to break away, taking a sizable chunk of the wing with it. Miller maintained control and completed an uneventful landing.

Norman Lee Barr (1907, Myrtlewood, Mississippi – 1979, Detroit, Michigan): Norman Barr started out flying in the U.S. Army Air Corps, graduating from flight training at Kelly Field on 12 November 1929. Commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Air Corps Reserve, he was placed on active duty, serving first at Mitchell Field, Long Island, New York, before being transferred to France Field in the C.Z. He flew with various squadrons, including the 99th Observation Squadron, the 24th Pursuit Squadron and the 25th Bombardment Squadron. Although it is not certain when he started, Barr was one of the active duty military aviators who began moonlighting for Isthmian Airways. Barr’s U.S. Navy – yes, Navy – biography states that he left active duty in August 1931, still apparently holding his reserve commission, and went to work full time for Isthmian Airways, sometimes listed as the airline’s chief pilot.

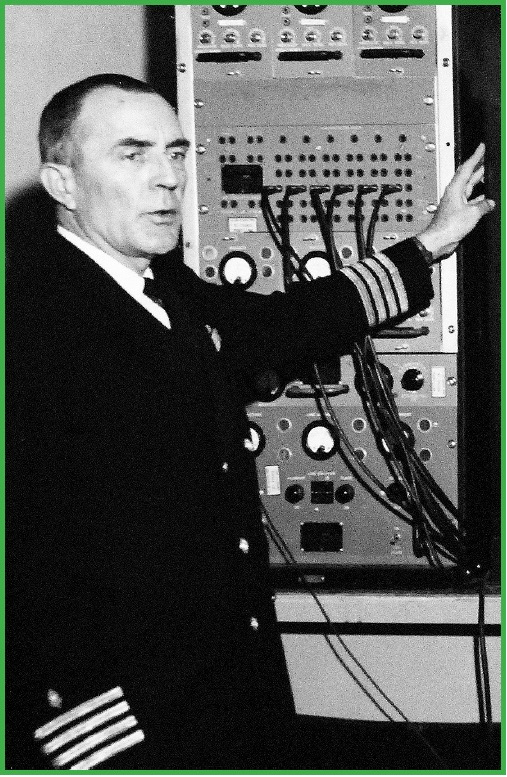

Leaving the C.Z. in August 1933, Barr attended the Georgetown School of Medicine, Washington D.C., and subsequently interned at Georgetown Hospital. In July 1938, he was commissioned on officer in the Medical Corps, U.S. Navy. Trained initially as a flight surgeon, Barr complete a long, fruitful career in the Navy, with an emphasis on aviation medicine, ultimately raising to the Directorship of the Astronautical Division of the Bureau of Medicine, retiring in 1959. He earlier had completed training and was designated a Naval Aviator in 1943. He is interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

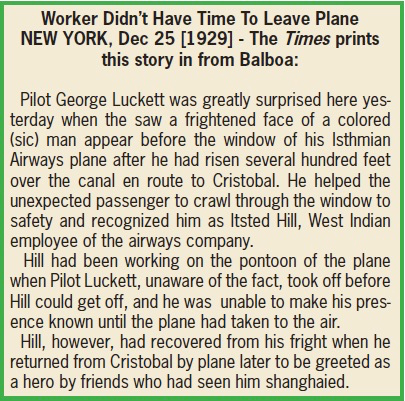

George F. Luckett (1901, Dresden, Missouri – 1989, Durham, North Carolina): George Luckett enlisted in the U.S. Navy 16 July 1920, rising to the rank of Aviation Machinist’s Mate First Class. In the mid-1920s, he was picked up for flight training as an enlisted Naval Aviation Pilot, pinning on his Wings of Gold in 1927. For the next several years his career is a bit murky, but he was apparently stationed in the C.Z., where he was one of the moonlighting pilots for Isthmian Airways. By late 1932, still in the Navy, he was back in the U.S., and a flight instructor at the Naval Academy. He may have returned to the C.Z. in the mid to late-1930s. In November of 1941, he was commissioned an officer, pinned on his Ensign bars, and was stationed at Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola as an instructor. It seems most likely that he stayed stateside during the war. He pinned on the rank of Lieutenant on 1 July 1944, and ultimately retired on 1 August 1946.

Stanley Enders LaParle (1904, Chicago, Illinois – 1936, Waukesha, Wisconsin): Stanley LaParle (sometimes spelled La Parle) was a member of an aviation oriented family. Ottillie “Tillie” LaParle was the matriarch, and she raised three aviator sons. She was also noted, in 1927, as the first and only woman then living in Chicago who owned her own seaplane – a Curtiss MF flying boat (N-ABCX) – although she was not a pilot herself. Her oldest son was Walter (born 1896), who had learned how to fly in 1915, and eventually joined the U.S. Army Air Service. By 1921, he was back in Chicago running a seaplane service out of the Edgewater Beach Hotel. Tillie’s next son was Edgar (born 1902), and although it is not certain when and where he learned how to fly, by the mid-1920s he was active in Chicago area aviation. On 15 March 1937, he sighed on with Northwest Airways (later Northwest Airlines – NWA), and during World War Two he was part of a cadre of NWA pilots who volunteered to fly cargo missions over The Hump, in China. Unfortunately Edgar was the captain aboard the ill-fated NWA Lockheed L188 Electra – Flight 710 – that disintegrated in flight near Cannelton, Indiana, on 17 March 1960.

Tillie’s youngest son was Stanley, and while it is also not certain when and where he learned how to fly, it was perhaps in the U.S. Navy, as he is noted in 1927, as a Naval Reserve aviator stationed at NAS Great Lakes. In any case, by the mid-1920s he was an active civilian pilot, often appearing in the news along with his brother Edgar. In 1927, Stanley was also reported as owning and operating his own airport in the Chicago area. In the May 1927, issue of Aero Digest, LaParle was listed as the Chief Pilot of the Chicago Aeronautical Service (did he know Jack Miller?). In May 1929, he was flying for a company called Weeks Aircraft Corporation, demonstrating the latest Velie Monocoupe light civilian airplane. It is not exactly certain, but Stanley LaParle must have hired on with Isthmian Airways soon after the company began operations. If LaParle did know Jack Miller, while both were flying in Chicago, perhaps it was Miller who offered him a job at Isthmian Airways. In any case, his tenure with Isthmian Airways was short as by Spring 1932, he was back in the U.S., suffering from the effects of either malaria or yellow fever. On 16 May 1932, it was reported that in a state of depression, brought on by the ailment, LaParle tried to take his own life, which was not successful. It is not certain whether he resumed any flying activities, but apparently still suffering the effects of fever, on 6 November 1936, LaParle again attempted suicide, and this time, tragically, he was successful.

Frederick Thorne Sterling (1905 Missoula, Montana – 1996, Miami, Florida): Frederick “Fritz” Sterling graduated from Montana State University, where he studied law, and played basketball. In October 1930, he completed flight training and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve. Having a two year active duty commitment, in early 1931, Lieutenant Sterling was shipped south, assigned to a squadron at France Field, in the C.Z. It was while serving this tour that he apparently joined the ranks of those active duty pilots who moonlighted with Isthmian Airways. With his commitment met, it is not certain whether he remained on active duty, and still flew part-time for Isthmian Airways, or if he left active duty to fly full-time for the airline. In any case, in 1934, he signed on with PANAGRA, thence flying three decades with that company until he retired in 1965.

In March 1939, while with PANAGRA, Sterling was one of the company’s pilots who flew a number of relief missions in Chile, after that country was hit by a devastating earthquake. For his, and several other pilot’s work, the Chilean government awarded them the Orden de Merito – Order of Merit. As a side note: It is almost certain the Fritz Sterling and Jack Miller knew each other, possibly in the Army, as well as at Isthmian, but certainly at PANAGRA. In a June 1950, newspaper advertisement extolling the safety and dependability of PANAGRA, there appears photos of six of the company’s most senior pilots, including both Sterling and Miller.

Burton Brown Barber (1892, Rochester, New York – 1941, near Bay Springs Mississippi): It must have been the lure of the sea that influenced Burton Barber to leave his hometown of Rochester, New York, and join the U.S. Navy on 21 May 1910. Even when he left the Navy in 1918, he traveled the world as a Chief Mate in the merchant marine, before re-enlisting back in the Navy in June of 1922. It was during his subsequent tours aboard NAS Pensacola, Florida, that he was trained as an enlisted Naval Aviation Pilot, later flying there as an instructor pilot. He again left the Navy in 1929, being one of several Naval Aviation Pilots who signed on with the New York, Rio, Buenos Aires Line (NYRBA). Barber flew some of the pioneering routes with NYRBA, and was soon put in charge of the Para, Brazil sector. Barber also seems to be one of several Naval Aviation Pilots that were let go when PAA took over NYRBA. From there, in 1930, he signed on with Isthmian Airways, often referred to as the company’s chief pilot. In the early April 1936 issues of several nationwide newspapers Barber was featured in an installment of Ripley’s “Believe It or Not.” Barber’s claim to fame was that he had logged more trans-continental, non-stop – Pacific to Atlantic, and back – flights than any other pilot – at the time a total of 5,504 trips. He ultimately made 5,821 crossings, carrying over 20,000 passengers without incident.

With the closure of Isthmian Airways, Barber moved back to Florida, bought a farm outside of Pensacola, and settled to a retired life as a farmer. In August 1940, Barber was back in the Navy, back aboard NAS Pensacola, and after completing a refresher course, he was back in the air teaching fledgling aviators. On 24 September 1941, Barber was part of the crew of a Navy R2D (Douglas DC-2) en route from St Louis, Missouri, back to NAS Pensacola, when around 2 miles southeast of the town of Bay Springs, Mississippi, the aircraft enter a “heavy electrical rainstorm,” and crashed. All four people on board perished. An article noted that at the time of his unfortunate demise Barber, at the age of 49, was the oldest Chief Petty Officer in the Navy.

Robert Oswald Marstrand (1911, Cristobal, C.Z. – 13 September 1939, on Cerro de la Trinidad, near Bejuco, Panama): When Bob Marstrand was a boy growing up in the C.Z., he ran with a group of five kids that christened themselves the Morgan Avenue Gang, called such for the Morgan Avenue neighborhood where they all lived and went to school. In June 1930, Marstrand logged his first solo flight, in Isthmian’s Travel Air E-4000. He and three other locals – Bruce Fox, John Reese and Panamanian Rodolfo Estripeaut, Jr. – had taken their flight instruction at Isthmian Airways, under the tutelage of Captain Jack Miller. In 1931, Marstrand then went north to attend various flight schools in the United States, before returning to the C.Z. later that year, where he, and his old classmate Rodolfo Estripeaut, both signed on as pilots with Isthmian Airways.

It was also in 1931, that the Republic of Panama organized a government sponsored airline called the Departamento de Aviación Nacional, which, among other things, would carry the mail – El Correo Aéreo Nacional – throughout the county. This service was inaugurated on 28 November 1931, with service on both the Pacific and Caribbean coasts. El Ruta del Pacifico was flown by Marstrand, with Estripeaut as his copilot, in a Keystone-Loening K-84 Commuter amphibian, that was christened “3 de Noviembre.” The route included, at times, Panama City, Taboga, La Chorrera, Bocas del Toro, Bejuco, Antón, Penonomé, Aguadulce, Santiago de Veraguas, David, Puerto Armuelles and Colón.

It is not all that certain how long Marstrand, or Estripeaut flew for either Isthmian Airways, or the Departamento de Aviación Nacional. Mentioned should also be made that Marstrand was, as noted in the December 1934, issue of Aviation, the president of the Canal Zone Aeronautic Association.

On 21 August 1933, a local Panamanian named Enrique Malek, founded an airline called Aerovías Nacionales, with the intention to operate throughout the Republic of Panama. Aerovías Nacionales was based in the city of David, Panama. It was around 1935, that Marstrand began flying for Malek’s airline, perhaps due to the turmoil that was then encompassing Isthmian Airways.

On the morning of 13 September 1935, Captain Marstrand was in command of a flight on a routine run from Panama City back to the city of David, Panama, about 225 miles to the west. There is some confusion on the type of aircraft flown, with one source saying it was a “tri-motor ship,” while others state it was a single-engine Travel Air A-6000. The latter may not be correct as the Travel Air A-6000 was a six-seat aircraft, at best.

By that afternoon the aircraft, with Marstrand and eight passengers aboard, had not arrived, The U.S. Army launched eight aircraft out of Albrook Field to search for the missing airplane, however all returned with no success. More search and rescue missions were launched the next day. One of the passengers on board the tri-motor was Juan Pino, the mayor of David, and it was his brother Manuel, Comandante of the National Police, who soon commenced a search on foot. Locals told Comandante Pino that they had seen a aircraft descending through bad weather and crashing on a nearby peak called Cerro de la Trinidad (Trinidad Hill). It took 15 hours, with locals as guides, before Pino’s search party reached the crash site. Marstrand, and his eight passengers, had all perished in the crash. Marstrand’s remains were carried out of the jungle, while to eight passengers were buried at the site.

When the news of the demise of their old friend became known, members of the Morgan Avenue Gang convened a plan to place of a commemorative bronze plaque at the crash site. Although not confirmed in any contemporary news reports of the day, it may be assumed that the plan was carried out, and the plaque is still there today.

Rodolfo Estripeaut, Jr. (4 May 1907, Panama City, Panama – 24 July 1954, Bolivia): Much of what is known about Estripeaut’s flying career is based on his association with Robert Marstrand. If he later quit flying the details are not readily known. Later in life, he did appear to become a member of the Panamanian diplomatic corps.

Robert Theodore Zane (1894, Sellersville, Pennsylvania – 1988, Hollywood, Florida): This was not the first time First Lieutenant Robert T. Zane, of the U.S. Army Air Corps, had worked in the CZ. In 1911, just after graduation from high school, in Sellersville, Pennsylvania, he and his two brothers – Hysler and Fred – headed south to work in the Panama Canal. Records show he worked as a wireman, in the electrical division, making 44 cents per hour. After the canal opened in 1914, that August, Zane returned to the U.S., entered Pennsylvania State University, and earned a degree in animal husbandry. His plans to become a veterinarian were changed when he enlisted, as a private, in the U.S. Army on 14 August 1917. Then, on 6 June 1918, he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant, and ordered to flight school. Being in training for remainder of the United States’ involvement in the war, Zane never deployed overseas.

After a number if flying assignments, Zane was ordered to the C.Z. to work with the Department of Commerce, Aeronautical Branch in the role as an aviation inspector. This position came about from a request of the governor, presumably Harry Burgess, of the C.Z. to the Secretary of War for a staff expert “in the matters of aviation.” Among other duties, the job entailed conducting surveys of airports and landing fields, conducting examinations and tests of applicants for pilot, mechanic and parachute rigger, issuing and renewing licenses for aircraft, inspecting aircraft, and in general the supervision and regulation of air traffic. First Lieutenant Zane reported to the Governor Burgess on 15 June 1929, as the Senior Aeronautical Inspector, to “render advisory services in addition to his regular duties with the Army.” One thing Zane was noted for while in the C.Z. was the development of a aerial spraying system in a valiant attempt to eradicate the ever-present scourge of mosquitoes in the Zone. Zane was in this position until he was reassigned to a stateside command in September 1935. He would go on to high level command positions, including several during World War Two, before finally retiring from active duty in 1949.

Joseph Malachi Short (1900, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 1978, Miami, Florida): There is not too much data readily available on Joe Short, but he appears to be one of the moonlighting pilots for Isthmian Airways.

There are a couple of brief newspaper accounts dating back to the early 1930s, both from the Philadelphia area, stating that he had just completed his commercial pilot’s license (May 1930), and another noting he had become the chief instructor pilot with the Eastern Aviation School (September 1932), having just completed two years of flying with the William Penn Aircraft School. Whether or not this is the correct Joe Short is open for discussion.

What is reasonably well documented is that by 1934, there was a Joseph M. Short living in the C.Z. and working as a mechanical engineer. In November 1936, Short married Norma Davis, who after graduating from Cristobal High School in 1934, had gone to work for Isthmian Airways. In the March 1991, issue of the Canal Record, there is a short piece on a get together of a group of former C.Z. residents, which listed Norma (Davis) Short, with the following notation: “Norma’s husband Joe was a pilot for Ralph Sexton on the Isthmian Airways.”

With the demise of Isthmian Airways, Joe and Norma Short, moved to Lima, Peru, where Joe got a job, presumably flying, for the Compañía de Aviación Fawcett airline. By 1940, they were back up in the C.Z., with Joe now employed by the U.S. Army, again as a mechanical engineer, from which he finally retired in 1966, and the couple moved up to South Florida.

There is one final mention of Joe Short in the C.Z., this one in connection with a flying school then being established by Marcos Gelabert. Joe Short was listed as one of the instructor pilots. Set up in late 1945, it is not certain whether or not Short actually worked for the firm.

And finally…

Gene Vacher Sexton (1919, Colorado Springs, Colorado – 2012 Hendersonville, North Carolina): There is an often-repeated tale that Ralph Sexton’s daughter “Genie” was a pilot herself, and at times flew for her father’s airline. Seeing that see was maybe nine years of age when Isthmian Airways began, and was perhaps seventeen when the airline shut down, this supposition is rather far fetched. She did take a few flying lessons in the Travel Air, but never actually soloed.

About the Flight School

Based in Balboa, the flight school founded by Ralph Sexton was sometimes referred to as the Isthmian Airways School, and at other times simply as the Sexton School. In early May 1929, almost concurrent with the commencement of service at Isthmian Airways, Sexton began to advertise in The Panama American newspaper informing the public about his proposed flight school. The ad noted: “If sufficient interest is shown we will offer seaplane training under competent instructors in the near future, with excellent new training planes.” Evidently, there was sufficient interest, as in a 12 July 1929, article in the newspaper it is recorded that the school would commence within a few weeks, that a new training plane – a Travel Air – would soon arrive, and that first class was full.

Most references note that Jack Miller was the main, if not only, flight instructor. References also note that training was conducted in both the Travel Air and the Hamilton Metalplane aircraft. While there may be a roster of students tucked away in some old file folder, from various articles a partial roster can be compiled. While a few early aviators living in Panama went to the Military Aviation School, at Campo Columbia, at Havana, Cuba, the following men learned to fly at the Sexton school: Eustació Chichaco, Nicanor de Obarrio, Jr., Rodolfo Estripeaut, Jr., Bruce Fox, John Reese, Ramón Arias (possibly trained in Cuba), Enrique Malek (also possibly trained in Cuba) and Robert Marstrand. There were probably a several more, as an article in the January 1930, issue of Aero Digest notes the first class had sixteen students.

At the time, these students were in ground school, and although the Travel Air biplane was there, it had arrived in November, Miller was awaiting the arrival of the pontoons so actual flight training could begin. By June 1930, the first students to receive their pilot’s licenses were Reese, Estripeaut, Fox and Marstrand.

Isthmian Airways’ Fleet

Without access to firsthand documents from back in the day, it is somewhat difficult to provide a definitive list of the aircraft flown by Isthmian Airways. Through the use of various references, databases, publications – both of the day, and more recent – as well as a few online websites, and a few personal contacts, it is possible to put together a semi-accurate, but certainly not definitive, list of the Isthmian Airways fleet. Again, this is just a reasonably well-educated guess.

| Type | MSN | Registration |

| Hamilton H-47 Metalplane | 64 | C.Z. 101 |

| Hamilton H-47 Metalplane | 60 | C.Z. 102 |

| Hamilton H-47 Metalplane | 46 | C.Z. 104 |

| Hamilton H-47 Metalplane | 47(?) | C.Z. 105 |

| Hamilton H-47 Metalplane | 49(?) | C.Z. 106 |

| Hamilton H-47 Metalplane | 51(?) | C.Z. 107 |

| Travel Air E-4000 | ?? | C.Z. 103 |

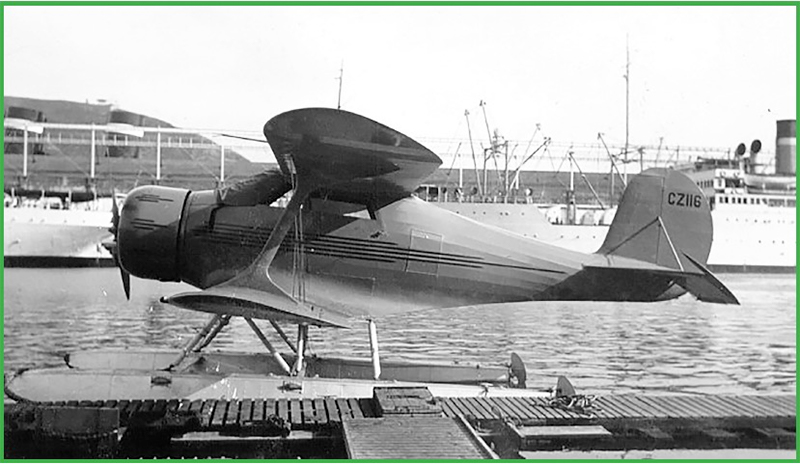

| Beech B-17L Staggerwing | 48 | C.Z. 116 |

A couple of abbreviations:

A.B. – Department of Commerce, Aeronautics Branch, created by the Air Commerce Act of 1926, to exercise control over the burgeoning world of commercial and civil aviation. After a couple of more organizational iterations, it eventually evolved, in August 1958, into today’s Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

MSN – Manufacturer’s Serial Number, alternatively referred to as the Construction Number (C/N), or simply as the Serial Number (S/N). These numbers were assigned by the factory to each individual airframe. For the sake of continuity, MSN will be used here. Not to be confused with a registration number.

Through a number of photographs, some of Isthmian Airways’ fleet of Hamilton Metalplanes can be reasonably well confirmed. As mentioned, for some of these aircraft, which MSN is associated with which C.Z. registration, however, is not readily known. Also, the delivery schedule is not certain. One reference (Aero Digest, December 1929) notes that two were initially delivered and in operation by the end of 1929, with the remaining airframes arriving later. Another reference notes that all the Hamilton Metalplanes were delivered in 1929, which almost certainly is not accurate. Aero Digest – June 1930 – had a short article on Isthmian Airways, in which it noted the airline’s third Hamilton Metalplane had just arrived. A search through other issues of this publication did not record the arrival of the other aircraft.

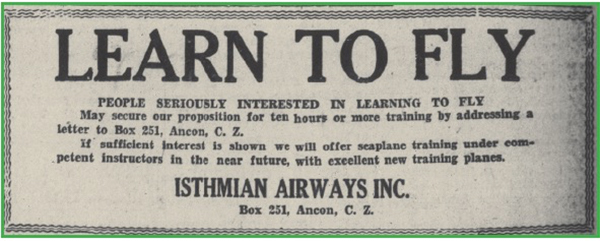

While both the Travel Air and the Staggerwing are fairly well known birds, built in reasonably numbers, the Hamilton Metalplane was a bit of an oddity. Briefly, the Hamilton Metalplane was built in small numbers by the Hamilton Metalplane Company, of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Incorporated on 12 July 1927 by Thomas F. Hamilton (1894 – 1969), whose name will always be associated with aircraft propellers, the Hamilton Metalplane Company was a division of the Hamilton Aero Manufacturing Company, itself founded in July 1920 (earlier in 1915, in Vancouver, British Columbia, if one counts his small company there), the builder of propellers, both wooden and metal varieties, as well as aircraft floats. After Hamilton decided that building entire airplanes was part of his future plans, he stood up the Hamilton Metalplane Company to concentrate on this venture.

Hamilton’s first successful design is considered to be the H-18, an all-metal, single-engine aircraft with a single shoulder-mounted cantilever wing. The Alclad metal skin used throughout the aircraft was corrugated to provide for rigidity, with out adding any undue weight. The first flight of the H-18, actually built under the auspices of the Hamilton Aero Manufacturing Company, was logged on 2 April 1927. It was a good ship, one that set a couple of records, and garnered a few trophies, including a couple awarded to Jack Miller. Only one was ever built.

Now with the Hamilton Metalplane Company underway, Thomas Hamilton toyed around with a few more designs before his Chief Engineer – one Dr. John Akerman – came up with the H-45 design. Still covered in corrugated metal, the H-45 was a straightforward, rugged aircraft, mounting a high cantilever wing, and powered by a single radial engine. The H-45 could seat 8 people – 7 plus the pilot. Another aircraft offered at the time was the H-47, which was essentially an H-45 with a bigger engine, to enhance performance. The H-45 was powered by a Pratt & Whitney Wasp of 450 horsepower, while the H-47 was powered by a Pratt & Whitney Hornet of 500 to 525 horsepower. Of course, adding a bit more confusion, individual owners often mounted an alternative engine, while not necessarily changing the aircraft’s designation.

Production numbers for the H-45 and H-47 are somewhat confusing, as some were ordered as H-45s, but rolled out of the factory as H-47s. Also, an H-45 could be later modified to H-47 specifications, and vice versa. Some guesses put the number at 30 airframes, while others go upwards of 50 airframes. While the Hamilton Metalplanes were productive aircraft for the era, it was probably simple business that did not see anymore airframes built. In January 1929, both the Hamilton Metalplane Company and the Hamilton Aero Manufacturing Company were both absorbed by the United Aircraft & Transport Company, a huge aviation holding company that also included the Boeing Airplane Company, the Chance Vought Corporation, the Stearman Aircraft Company, and the Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company, among several others. The Hamilton Metalplane Company was put under the control of Boeing, as the “Hamilton Metalplane Division of the Boeing Airplane Company,” which continued the construction of the H-45/H-47 for a very short time. In April 1930, the Hamilton Metalplane Company was closed.

As a side note: One other Hamilton Metalplane is known to have been operated in Panama. Built as an H-45 – MSN 56 – was originally sold in February 1929, to a man named Carl Keller. Prior to delivery it was upgraded to H-47 specifications. A year later, Keller sold the bird to Northwest Airways, who flew it for around seven years or so. It was then exported to Panama, registered as R-12, and was noted in the fleet of Transportes Aéreos Gelabert. With the coming of World War Two, the aircraft was impressed into the U.S. Army Air Corps on 14 August 1942, under the designation UC-89, and the Serial Number 42-79546. It was assigned to the Panama Air Depot, and was the only example of a Hamilton Metalplane ever to go into military service. Found to be less than suitable for its role, the airframe was struck off charge on 24 August 1943, and was most likely scrapped.

Isthmian Airways’ Hamilton Metalplanes

C.Z. 101: MSN 64. This airframe was built in February 1929, and initial paperwork indicates it was originally intended to be a landplane, to be used by the Hamilton Metalplane Company as a demonstrator aircraft. It was assigned the A.B. identification number 533, as an unlicensed aircraft. In a letter dated 20 February 1929, Hamilton’s Vice President Charles F. Barndt informed the A.B. that the airframe was now to be completed as a seaplane, and had been sold to Ralph Sexton, who was then in Cartagena, Colombia. For a time there was a bit of confusion on exactly what A.B. identification/license number should be assigned to this ship. In a 2 March 1929, cablegram from Sexton to Hamilton, Sexton requests the company secure a license number from the A.B. for the aircraft to be used on “Transisthmian Passenger Service.” Hamilton forwarded the request to the A.B. For the next couple of weeks a number of letters and telegrams between the A.B. and Hamilton went back and forth discussing just how to license this aircraft. The identification number 533 was ultimately assigned on 30 March 1929. In the meantime, the airframe had been shipped to Panama, vice Colombia. In April, Hamilton – now part of the Boeing Airplane Company – returned the identification plate – number 533 – to the A.B., noting in a 5 April letter that the aircraft would be assigned an identification number by the government of the C.Z., ultimately C.Z. 101. On 16 April 1929, the identification 533 was canceled by the A.B.

By the second week of April 1929, local C.Z. newspapers were reporting that this aircraft, described as an “all-metal eight place job,” had arrived – by ship – and was then being assembled. Jack Miller, who was at the time flying down in South America, was too soon arrive to do the test flights.

C.Z. 102: MSN 60. While the above noted confusion on exactly how the A.B. should register MSN 64 played out, Hamilton was putting the finishing touches on MSN 60. In a letter dated 26 March 1929, to the A.B., Hamilton stated that MSN 60 was to be mounted on a set of pontoons, and should be ready for flight test no later than 18 April, and thus needed an identification number to legally fly. Paperwork submitted by Hamilton to the A.B. notes that this airframe was completed in March 1929. On 19 April, the A.B. assigned the unlicensed identification number 2917 to MSN 60. This number was returned to the A.B. in May 1929, when it was noted that the airframe “was shipped to R.E. Sexton, Balboa, Panama Canal Zone.” A Bill of Sale, dated 18 May 1929, transferred MSN 60, from Hamilton to R.E. Sexton.

In June 1929, with MSN 60 now in the C.Z., there still appeared to be some uncertainly amongst the authorities on how to register Isthmian Airways two aircraft. The question was whether the aircraft should carry A.B. identifications or C.Z. identifications. In the end, they would be assigned C.Z. identification/registrations. To put an end to the discussion, in a letter dated 20 June, the A.B. informed Sexton that: “It is not necessary for you to register your plane with this Department for operation in the Canal Zone.” This letter also noted the identification number 2917 was canceled.

As a side note, these first two ships in the Isthmian Airways fleet were purchased by Ralph Sexton, and then later transferred via a Bill of Sale to Isthmian Airways Incorporated.

C.Z. 104: MSN 46. As noted by eminent aviation historian John Davis, this aircraft “had a charmed life,” as it had suffered major damage, and was subsequently rebuilt, no less than three times. Built in August 1928, MSN 46 was originally intended to be a Wasp-powered H-45, but this was switched to a Hornet-powered H-47 sometime prior to completion. The first inspection report notes that this aircraft was, indeed, powered by a Pratt & Whitney Hornet, and was thus an H-47. It was sold to Universal Air Lines System (more on Universal below), of Chicago, Illinois, and was only flown on the line for a few months before the first accident occurred. On 3 December 1928, on a night run from Chicago to Cleveland, Ohio, the pilot, named James Ingram, decided he needed to land due to poor weather. He selected what was described as a “U.S. Air Mail emergency landing field,” near Goshen, Indiana. Ingram dropped a few landing flares to illuminate the field, and although they failed to ignite, he still attempted to land. About 20 feet off the ground, the wing of the Metalplane caught a tree, landing heavily. In the A.B. files, damage to the airframe was described as: “Right wing bent and broken, landing gear broken, motor fell out, prop bent, wheel broke, left wing top damaged.” Still, under the entry “Owner’s intention to rebuild,” the answer was “Yes.” The pilot and passengers on board survived with slight injuries.

The airframe was quickly repaired and was reinspected on 25 January 1929. It was during these repairs that the Pratt & Whitney Hornet was swapped out for a 525 horsepower Wright Cyclone radial engine, an option that was approved by the A.B. MSN 46 was back on the line for only a few days when, on 30 January 1929, it was damaged again, although the circumstances of this event are obscure. Records are scare, but it seems that a pilot by the name of George J. Brew was at the controls when the damage occurred. Damage was listed as: “Landing gear, left wing and propeller damaged.” What happened and where it happened is not clear. Again, for the entry “Owner’s intention to rebuild,” the answer was “Yes.” Repairs were quickly completed, and the ship was reinspected, and approved for flight, on 6 February 1929.

Finally, on 21 October 1929, with pilots James Ingram and Walter Hallgren in the cockpit, this bird, still part of the Universal fleet, was involved in yet another crash. As one newspaper (The Chicago Tribune) described it: “they were cruising through the murky atmosphere searching for Municipal airport beacons,” when their Cyclone engine suddenly quit. The pilots later claimed that the engine quit on account of a clogged fuel line, while subsequent investigation found the fuel tank was dry. Regardless of the cause, the pilots completed a forced, dead stick landing in an open piece of land at the intersection of 77th Street and Western Avenue, some 8 miles south of downtown Chicago. Although the landing itself was reasonably well executed, the aircraft ending up nosing over in a ditch, and came to rest on its back. Both pilots emerged unscathed, while a mysterious passenger was seen departing the scene before he could be identified. In the A.B. file the damage was noted as: “Rudder, vertical fin, motor and mount, cowlings and cabin windows damaged. Prop slightly bent.” Once again, for the entry “Owner’s intention to rebuild,” the answer was “Yes.”

MSN 46 was dismantled and shipped back to Hamilton for another round of repairs, however, by late March 1930, the ship was noted as in storage at the Hamilton Metalplane facility still awaiting these repairs. Records indicate that Hamilton did rebuild the ship, however it never rejoined the Universal fleet. Also, no extant paperwork records a current inspection of the airframe. During the course of this rebuild, the airframe was apparently fitted with floats. On 9 October 1930, MSN 46 was sold to Isthmian Airways and was subsequently shipped, without an engine, down to the C.Z., where it was registered as CZ 104. John Davis opined that Universal and Hamilton were probably happy to see it go.

C.Z. 105, C.Z. 106, C.Z. 107: MSNs 47, 49, 51. Of these three airframes a few facts are reasonably certain. All were Hornet-powered Hamilton H-47 Metalplanes, all were landplanes, and all were completed in the fall of 1928 – MSNs 47 and 49 in September, and MSN 51 in October. All were originally sold to business entities under the umbrella of what was called the Universal Aviation Corporation, itself founded a few months earlier on 30 July 1928. MSNs 47 and 49 were initially assigned to the Twin Cities-Chicago Air Lines, while MSN 51 was assigned to the Universal Air Lines System. What followed in the next few months, which is much too tedious to describe here, was a series of corporate machinations where these airframes were bought and sold between air lines within the Universal Aviation Corporation, until in May 1929, all three were “sold” to Braniff Air Lines, itself also part of the Universal Aviation Corporation. Finally, in January 1931, all three airframes were sold by Braniff Air Lines to Ralph Sexton, and Isthmian Airways.

The quandary surrounding these three ships is that it is not exactly certain which C.Z. registration number corresponds to which MSN. The A.B. records end with the sale of the airframes to Isthmian Airways, and thus provide no clues.

What is certain is that while still owned Braniff, the condition of these three airframes was somewhat suspect, and in fact, none, in the eyes of the A.B. were even airworthy. As for MSN 47, during the last A.B. inspection, completed on 30 October 1930, an inspector named M. Clark noted: “Ship has been in storage for several months – not being used. Needs a good general overhauling and reconditioning before putting into service again.” Regarding MSN 49, a letter from Gilbert G Budwig, the A.B. Director of Air Regulation, dated 9 December 1930, informed Braniff that: “Your Hamilton aircraft, model H-47, manufacture’s serial number 49, has been disapproved for relicensing by a Department of Commerce inspector [a man named Hughes, on 29 November 1930], due to the fact that the aircraft fails to meet the airworthiness requirements of this department.” Mr. Hughes noted that MSN 49 had been: “in storage, partly disassembled, some instrumentation missing,” as well as having a poorly fitting cowling, and had some of its metal wing covering missing. Finally, at the completion of the last inspection of MSN 51, on 19 August 1930, an A.B. inspector named Delaney disapproved the airworthiness of the aircraft, noting: “Motor in bad shape and ship in storage, needs full overhaul of ship and motor.” In many of the sections of the inspection report he wrote in big letters: “Ship needs full overhaul.” Quite oddly, it seems that within the span of only a handful of years these three Hamilton Metalplanes went from brand new, airworthy aircraft to being not airworthy and grounded.

If Braniff brought these airframes up to airworthy condition prior to the sale to Isthmian Airways it is not recorded in the A.B. files. Nor does any A.B. paperwork indicate that they may have gone back to Hamilton for overhaul, and indeed, all of the extant documents indicate that Ralph Sexton bought them directly from Braniff, in whatever condition they were in. Once in the C.Z., presumably they were shipped down there in crates, did Isthmian Airways have the capability to do complete overhauls on the ships? Were these overhauls ever completed? Now, the following assumption is based on circumstantial evidence only, and is simply a theory, and may not even be a valid idea. Based on the letters – noted in the main text of this article – from C.Z. Governor Schley to Ralph Sexton, concerning the dubious condition of some of his aircraft, the question arises whether or not these three aircraft were one of the reasons the governor decided to shut down Isthmian Airways. Did Lieutenant Zane take a look at these birds and then determine they were not airworthy?

The ultimate fate of the Hamilton Metalplane fleet is also a bit obscure. One reference posits that after the closing of Isthmian Airways, all the Metalplanes were sold, and flown south, to an unrecorded fate. That said, in the December 2013, issue of the Airpost Journal, there is an article titled “Robert Marstrand and Isthmian Airways,” written by the late Alan P. Bentz, who was a young boy growing up in the C.Z. at this particular time. Mr. Bentz recalls that with the demise of Isthmian Airways: “The planes were stacked up on their noses across from Pier 18 [Balboa’s inner harbor], and myself and many other youngsters used to look at them rusting away.” He continues: “My own memory was of their wicker seats and the instrument panels that had been smashed with sledge hammers to make the planes inoperable.”

Likewise, in an article titled “The Little Airline That Could,” by Luis R. Celerier, that appeared in the March 2013, issue of the Canal Record (a publication of the Panama Canal Society), Mr. Celerier relates that as a youngster growing up in the C.Z. he used to enjoy watching Isthmian Airways airplanes take off and land. Then, after the demise of the airline, he recorded: “We made one last visit [to Pier 18, at Balboa] soon after the war started, but this time only to peek into the hangar and see the littles planes stacked, standing on their noses, waiting for the war to be over.”

C.Z. 103. Regarding the Travel Air E-4000, as noted above, it is reasonably sure that it was part of the Isthmian Airways fleet in 1929. In the September 1929, issue of Aero Digest, there is a short article about how Isthmian Airways had just purchased: “a Travel Air biplane, equipped with pontoons and a Wright Whirlwind (sic) engine, to be used as a training plane.” Another article, in the 5 October 1929, issue of Aviation noted the Travel Air: “went to the Isthmian Airways of Cristobal, C.Z. It will be equipped with pontoons and used for training purposes.” Once the aircraft arrived in the C.Z. it was mounted on Edo M-2665 floats, it was used for flight instruction, and although not confirmed, it may have been used for charter sight seeing hops. The Panama Canal Record, for the week ending 16 November 1929, notes that an aircraft, although the type is not noted, registration CZ-103, arrived in the C.Z. from the U.S. on the 13th of that month. Carrying the registration C.Z. 103, the MSN of this bird is not clear, nor was its ultimate fate.

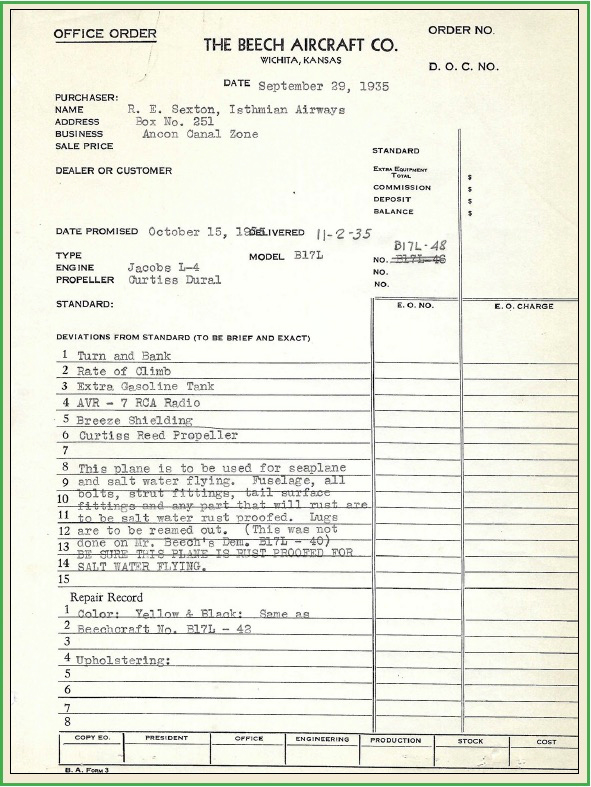

C.Z. 116. One of Isthmian Airways’ aircraft that is well documented, at least in its early operational life, was the Beech B17L Staggerwing. Documents held by the Beechcraft Heritage Museum, in Tullahoma, Tennessee, record that on 29 September 1935, Ralph Sexton ordered a Model B17L, to be delivered on 15 October. It was delayed a bit, and finally delivered on 2 November 1935, with a Bill of Sale stating that Serial Number (MSN) B17L-48 was sold to Sexton on 3 January 1936. The ship was noted as being yellow, with black accents. More importantly, as recorded on order form, there was a notation stating that;” This plane is to be used for seaplane and salt water flying,” and included specific instructions concerning corrosion control measures. This notation concluded – in all capital letters for emphasis: “BE SURE THIS PLANE IS RUST PROOFED FOR SALT WATER FLYING.” So a life on floats seemed to be in its future. When ready for shipment to the C.Z., a number of spare parts for the 225 horsepower Jacobs L-4 radial engine were included, such as a complete cylinder and head assembly, a piston with rings and pin, a complete set of gaskets, as well as various instruction manuals.

Records indicate that Sexton’s Staggerwing was registered as C.Z. 116 in October of 1935, although this would appear to somewhat predate the aircraft’s actually arrival in the C.Z. Sexton, along with a pilot named Harold A. Speer reportedly flew the Staggerwing down to the C.Z. All extant Beech paperwork indicated the airframe was built as a B17L landplane, so it is not clear when nor where it was mounted on floats, one assumption being that this installation was done in the C.Z.

With the demise of Isthmian Airways, how Sexton used his Staggerwing is not all too clear. There was one episode in 1937, that has Sexton flying the aircraft down to Colombia to be used on the movie Too Hot to Handle (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, released in 1938) starring Clark Gable and Myrna Loy. As to the ship’s eventual fate, this is also not clear. One source, lacking in any corroboration, posits that in the late 1930s (year?), the ship was simply sold, and flown south into obscurity. This could be true, but again this theory is rather short on evidence. A more credible source, a Mr. Georges Bouche, relates that in the late 1930s/early 1940s, the aircraft was placed in storage, and then later seen, in very poor condition, in a scrapyard near the harbor at Balboa. He says that in the early 1940, this Staggerwing was shipped by rail out of the C.Z., although which way it went – north or south – and its eventual fate in not certain.

And finally, there is a somewhat confused notion out there that says Sexton, in 1939, after disposing of C.Z. 116, bought another Staggerwing and registered it as C.Z. 116 also. What makes this supposition hard to accept is that the MSN associated with this second Staggerwing was reportedly “1135.” Now, under the Beech system of MSNs of that period, this would be somewhat problematic as the number “1135” would have been assigned to a Beech AT-7-BH Navigator (41-21120), delivered to the Army on 14 November 1941. So, without further information, the idea the Sexton had a second Staggerwing can be discounted.

Regarding Harold A. Speer (1899, Oklahoma – 1977, Lima, Peru), he was another of those aviators of the period that lived a fascinating life, and occasionally popped up in the aviation press. In 1917, he joined the U.S. Army Air Service, and was later shipped to France to become part of the as yet to be commissioned 1103rd Aero Squadron. Presumably he was then a pilot, but this is not certain. After the war, he moved around the world of flying, running his own flight school in Gardena, California, working as sales manager and demonstration pilot for the International Aircraft Corporations, builder of Fisk airplanes, competing in the odd flying derby, and setting a number of flying records. In late 1935, he flew with Sexton down to the C.Z., however what he did after that is not clear. Did he, perhaps, fly for Isthmian Airways for a time? In any case, by the early 1940s he was a airline pilot flying for PANAGRA. Later in life he was in the employ of the airline Lloyd Aereo Boliviano, as a technical advisor.

As a side note: The Beech Model B17L could be equipped with wheel landing gear, floats, or skis, all of which were governed under the same Approved Type Certificate (ATC) #560. Stipulations within ATC #560 allowed for the installation of EDO 38-3430 floats, which weighed in at an extra 452 pounds, changed the designation to SB17L, and upped the allowable gross weight from 3,165 pounds to 3,525 pounds. Interestingly, in Joseph P. Juptner’s book U.S. Civil Aircraft Series, Volume 6 (Tab Aero, 1994), the author notes that C.Z. 116 was actually a Model B17B, a landplane, with the difference being the installation of a 285 horsepower Jacobs L-5 radial, vice the standard 225 horsepower L-4 engine. This application was authorized in ATC #560, however if this was true concerning Sexton’s ship, the aircraft would have had the MSN B17B-48, vice what the known paperwork indicates as a B17L-48. A minor quandary that is difficult to confirm.

Author’s Note