Established at first as E.M. Laird Company in the early 20s, the Swallow Aircraft Manufacturing Company was based in Wichita Kansas, from where it produced the “First Commercial Airplane” named “Laird Swallow”, a three-place biplane powered by the inevitable OX-5 engine, and offered for US$6,500.00 for those wealthy enough to buy one. Other variants followed the “Laird Swallow“, some of them like the T-29 or F-28 were limited production, while the “New Swallow“, designed by Lloyd Stearman himself, reached the 50+ units built in 1926. A Curtiss Jenny look-alike, the Swallow had a wood and wire trussed fuselage, coupled to wings of the ‘single bay’ type. The Curtiss OX-5 engine produced 90hp, making the take-off runs very short and providing a good rate of climb. The Swallow was so dependable that Varney Airlines acquired five for flying the famous CAM 5 mail route.

The origins of two -out of three- of the Nicaraguan Swallows is linked to the San Francisco Checkered Cab Company, who sold them to Humberto Pasos Díaz, a wealthy Nicaraguan businessman, who intended to use the planes for carrying mail and limited cargo to and from Managua. These two Swallows, of which the exact model is unknown to this day, arrived in the Nicaraguan Capital in the Summer of 1926, right after the outbreak of the “Constitutionalist War” between the Conservative Government and the Liberal rebels. As it couldn’t have been otherwise, both biplanes were seized by the Government upon their arrival, and promptly pressed into military service. The pilots who had brought them to the country, named William Brooks and Lee Mason -both ex-U.S. Army pilots turned barnstormers- were appointed Majors of the incipient Guardia Nacional (National Guard) by the Government, and were sent immediately to patrol the waters near the Corinto Port, in the Pacific coast of the country, as there were rumors that the Liberal rebels were being resupplied by ship in that area.

One morning in August, a Mexican ship dropped its anchor near a beach located a couple of miles Northeast of Corinto Port, and began to unload its cargo into small boats, which in turn, carried it to the shore. The crates being transported contained arms, ammunition and supplies for General Moncada’s rebels. The small boats were about to reach the beach, when two slow biplanes arrived in the scene and positioned themselves for attack, leaving the sun in their backs to avoid being seen. While approaching the area, the two pilots reached for a bunch of four-foot-long, eighteen-pound home-made bombs that they were carrying in the cockpit floor and prepared to throw them at the Mexican vessel as soon as they passed over it. Such bombs consisted of dynamite and percussion caps set in containers weighted with metal.

One of those “bombs” exploded near the ship but caused no damage while the rest missed it completely. The ship’s crew opened fire at the biplanes with a machine-gun and small arms; the pilots in turn fired back with their rifles, which were the only weapons they were carrying. The pursuit went on for twelve miles, until the pilots ran out of ammunition. The very next day, during the late afternoon, one of the biplanes went on patrol over the beaches near Corinto and discovered the vessel once again, this time close to a beach near the Cosigüina Volcano, in the Gulf of Fonseca, unloading crates packed full of arms and ammunition. The pilot didn’t lose any time and dropped nine “bombs” which exploded close to the ship and fired at it with his rifle, only to be met with return fire from the ship’s machine-gun. In the end, the biplane was forced to withdraw due to darkness. By then, the rebel forces had overpowered the small garrison in Cosigüina, killing four men, and were getting ready to march inland, fully equipped with the arms that the ship had brought. Those attacks against the Mexican vessel, carried out by the two Swallow biplanes of the Nicaraguan Government, made it to the headlines of the New York Times. Both Brooks and Mason had also their share of fame for such feat.

On their part, the Nicaraguan Swallows are described in U.S. State Department records as “Hispano-Suiza Swallows” also known as “Hisso Swallows“, meaning that the biplanes were powered by Hispano-Suiza engines. Nevertheless, according to William Brooks, at least one of these was actually powered by a Curtiss OXX-6 engine (100 hp), while the other -the one that was acquired in 1927- had a Hispano-Suiza engine installed.

Battle for Chinandega

President Diaz’ first appeal for a full-scale American intervention reached the U.S. State Department on November 25, 1926, after having failed to end the revolution. Neither the promise of a high diplomatic post for himself nor the assurance of pay for his troops could induce General Moncada to lay down his arms unless ordered to do so by former Vice President Juan Sacasa. To make matters even worse, Sacasa himself arrived in Nicaragua days later, to take an active part in the revolt. With him came additional shipments of Mexican arms. In the meantime, Diaz kept up the clamor for further assistance from the United States.

Here’s worth noting that, by the late 19th century and the early years of the 20th, the U.S. Marines had been sent twice to Nicaragua. By 1925, after the political unrest was settled by free elections, the Marines were withdrawn from the country for the second time. However, since the early 1926, the Conservatives and Liberals were struggling for power once again. And as the Liberals, fed by continuing shipments of Mexican war materiel, were getting stronger each day, the President of the United States, Calvin Coolidge, maintained an icy silence. It wasn’t until a series of outrages were committed upon American citizens that his attitude began to change.

First off, the Liberals, or Constitucionalistas (Constitutionalists) as Sacasa called them, began imposing annoying “taxes” on American firms. In turn, the U.S. lodged a protest with Diaz and directed its nationals to ignore the Sacasa rebel government. It was, however, rather difficult to ignore the Constitucionalistas when so many of them had rifles. American businessmen, along the Pacific coast of Nicaragua, had been unable to prevent the rebels from seizing their supplies and equipment. Finally, in late December, an American citizen employed at Puerto Cabezas, was killed by the rebels.

Total disregard for American lives and property at last hardened President Coolidge’s heart against the Liberal cause and, in late December 1926, U.S. Marines landed at the towns of Río Grande, Bragman’s Bluff, and Prinzapolka -all located in the Caribbean coast of the country- with the mission of serving as a protective shield against the lawless guerrillas. On January 10, 1927, Coolidge informed Congress that he would do everything in his power to protect American interests in Nicaragua. Besides employing military force, Coolidge was to authorize the sale to the Díaz government of 3000 Krag rifles, 200 Browning machine-guns, and 3,000,000 rounds of ammunition. On its part, the Nicaraguan government acquired a third Swallow directly from the factory. This one has been reported as a truly Hisso-Swallow.

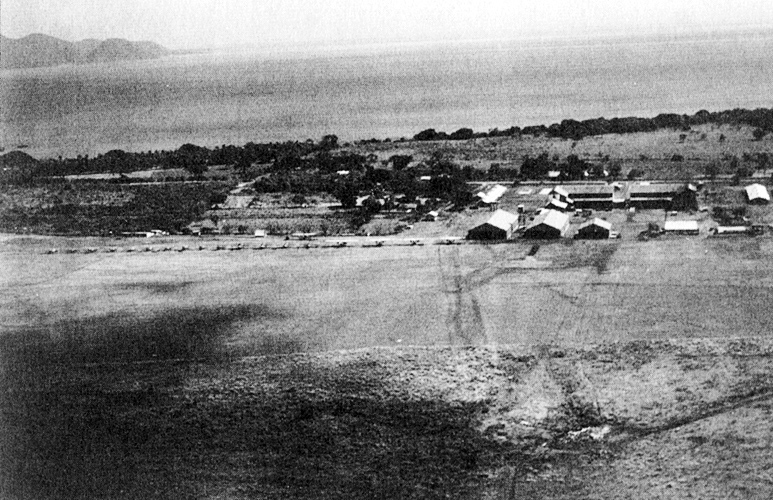

The strength of American forces in Nicaragua increased. The 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, arrived at Bluefields on January 10. After establishing a neutral zone along the Escondido River, the battalion, less the 51st Company at Rama, sailed from Bluefields through the Panama Canal to Corinto. On February 1st, at the request of President Díaz, Lieutenant Colonel James J. Meade’s Marines relieved government troops of responsibility for the defense of Managua.

In spite of the assurance of further U.S. aid, the fortunes of the Díaz government were taking a turn for the worse. Early in February, the Liberals captured Chinandega in a bloody house-to-house battle. Brooks and Mason were sent to work on the Swallows, attacking the rebels with dynamite sticks and fire from their rifles. Here’s a short narrative, written by William Brooks and published in the New York Times, about their operations over Chinandega:

“…The aerial operations in connection with the battle of Chinandega began on the morning of Sunday, February 6th. Major Lee Mason, Chief of the Air Service, had a car waiting at the entrance to my patio at 8:30 in the morning, with instructions to come at once to the flying field and prepare for a raid. The Liberals, I learned when I met him, had taken possession of Chinandega, the important city in the Western range of Nicaragua, and President Diaz had resolved to use the Air Force against it.

About noon, we took off, [Lee] Mason in the new Swallow plane, with a new Hispano-Suiza engine, carrying a Lewis gun and a camera; I used the older Swallow with the OXX motor, which limited the horsepower to 100HP at full throttle. Being underpowered, I could only take nothing but a camera, my automatic pistol and a rifle with some rounds of ammunition.

We climbed out of the valley in which Managua lies, then high above the mountains to get enough altitude to cross them safely. As we approached Chinandega, I looked closely for Díaz and Sacasa armies, which were reported to be operating around the city, but we could not see a moving thing anywhere on the landscape.

As we flew over the city, we realized that two blocks of the business section were burning, and the smoke was rising to an altitude of 5,000 feet. I took some pictures and then we proceeded to Corinto to study and learn the disposition of the troops.

At 5:00 PM I took off again for Chinandega and Managua and found conservative troops entrenched along the railroad leading to the hamlet of Philadelphia, which is about three miles from Chinandega. A good deal of firing appeared to be taking place and the blaze in the city had spread until nine square blocks were burning in a solid mass.

No one seemed to notice my ship as I glided down with the motor throttled back until I was at 500 feet above the city. Then machine-guns opened fire on me from three different places. I kicked the rudder violently for a few minutes and then thought of a trick to frighten my admirers.

Taking the empty case in which I had carried extra films for my camera, I filled it with some cartidges to make it fall straight and threw it overboard. Those three machine-guns shut up immediately. Even after enough time had elapsed for the gunners to discover that the ‘bomb’ was not going off, they stayed under cover. When darkness came I proceeded to Managua. The next morning I discovered that the Nicaraguans had put ten holes in my wings and fuselage while I was flying seventy miles an hour and kicking the rudder as hard as I could. Major Mason on his part, came back with eleven bullet holes in his ship and all were very near the pilot’s seat…”

The next day, Mason and Brooks were ordered to conduct a bombing raid upon Philadelphia. The Army was to be ready to attack at 11:00 AM, but first, one of the Swallows, piloted by Mason, was sent to drop a message to a detachment moving through the mountains, with orders to hurry forward. A couple of minutes later, Brooks also took off for Philadelphia, carrying home-made bombs in his cockpit. Here is Brooks’ narrative of the event:

“…About noon I got over Chinandega at an altitude of 2,000 feet. There was a great white patch in the green of the city. The ashes of the fire for which Major Mason and I were later blamed formed this splotch. There was no one visible in the city and I went on to my objective.

Although I could not see no one, soon I noticed that a patch of linen on the right wing had been ripped loose. A moment later, a trickle of gasoline came down from the emergency tank in the upper centre section, and then I knew the sharpshooters in the jungle were working on me. Just as I got over Philadelphia, a ball came through the floor of the fuselage, passed between my legs and punctured the linen on the trailing edge of the upper wing. I had about decided to be nice to the village and keep my bombs for a better day, but this made me angry, It wouldn’t do any harm to let them have one, I thought, and so I pulled the trip rod. That home-made bomb made more dust than a 100-pound missile would in a wetter country. The whole landscape seemed to rise.

When the dust settled, I saw Liberal troopers running in every direction. They took refuge now and then in clumps of srubbery and then darted away to another retreat. Some waved their hats in the air, and I guess they wanted to surrender. But when I dived on them, they ran and clung to trees.

By this time I had circled back over Chinandega, only three miles away, and the sharpshooters started to work again. A bullet passed through the leading edge of the lower wing, just back of the propeller, and I began to think it would be wise to do my job and get out of there. After I had figured out where the sharpshooters were hidden, I heaved a bomb at them.

The traffic jam that followed that explosion was probably the worst ever known in Chinandega. Someone must have told those people that the place to meet bombs was on the street. Men, women and children dashed up and down the streets, through the squares and back again. They seemed to be crazy, they ran so fast and aimlessly.

But the sharpshooters had not been scared this time and kept on puncturing my wings. There is no armor under the seats of these planes, and as I saw a hole appear in the aluminum seat of the front cockpit, I got to feeling very self-conscious. The main gas tank was leaking by this time and I had good reasons to head for Corinto. So, I found a vacant spot and let my last bomb go. That explosion started the running all over again. The people were still running and the marksmen still shooting at me when I left. The mechanics at Corinto counted fourteen holes in the plane when I landed.

Major Mason came in from his mission at 4:15 and he said that I ought to go back and help with the attack. When I got back there, the defenders waved a white sheet to me and I flew down the railway to the place where our own troops were deployed. First I dropped a message telling them the city was ready to surrender. Nothing happened. Then I looped and flew back and forth, throttled the motor and yelled to them to go and take possession of the city. But they stayed right where they were.

I tarried until it got dark and had to leave without obliging the Chinandegans by arranging a surrender for them. Next morning they had changed their minds and put up a battle when the Army advanced…”

Brooks pictured themselves like cowboys riding their winged horses, in the best “Far-West” style… And what a horse he flew! Upon returning from another mission, Brooks reported more than 30 hits from small arms on his Swallow! Nevertheless, the mechanics back at the airfield, always managed to repair it during the night, having it ready for combat the next day.

In the end, Government troops regained the town, but not before the heart of Chinandega had been burned and blasted to pieces by the Liberals, however, Brooks and Mason were accused by them of setting off the blaze with their bombs.

The U.S. Marines rushed food and medical supplies to the suffering Chinandegans; and on February 19, a reinforced Marine rifle company, together with landing parties from three cruisers, left Managua to post a garrison at the ruined city. There, the seamen kept the peace, while the Marines manned an outpost on the edge of town to guard against the sabotage of a railway bridge.

Epilogue

As the U.S. Marine Corps equipment in Nicaragua, especially aircraft, increased, the Swallows were relegated to more mundane duties and seldom used. History traces them to a point right after the Chinandega Battle, and then, the mysterious biplanes disappear. However, it seems that one managed to survive until 1930, while the others, almost for sure, were cannibalized or simply scrapped.

Almost all of the Swallows that were produced are accounted for, but these three, which left the U.S. right before the introduction of the “N” civilian registration system by the late 1926 and early 1927, are not recorded. As mentioned, historians haven’t agreed even on the exact type of these planes, sometimes calling them “Laird Swallows“, “New Swallows” or “Hisso-Swallows.”

All in all, the Nicaraguan Swallows’ air operations at Corinto, Chinandega and Philadelphia, represents the first major use of the airplane as an instrument of war in Central America. These early air operations demonstrated that the airplane was an especially valuable asset in Nicaragua for conducting reconnaissance, sending messages, and disrupting enemy concentrations through air support and interdiction operations.

As a matter of fact, U.S. Marine aviators expanded these concepts of close air support and independent aerial bombardment during their second intervention in Nicaragua. They refined other uses of air power by conducting reconnaissance, communication, transportation, and even special operations missions. In addition to these developments, the coordination between air and ground forces provided valuable experience prior to World War II. The Marine campaign in Nicaragua provided several lessons about the role of air power in counterinsurgency conflict, and such lessons are still applicable today. The amazing part of the story is that all of this was started by two smart pilots and their mysterious and elusive biplanes!

Sources

Book: Central American and Caribbean Air Forces, by Dan Hagedorn.

Article on the New York Times: American Fliers Fight for Nicaragua, published on Aug. 27, 1926.

Article on the New York Times: Chinandega Battle as seen from a plane, published on March 5, 1927, written by William Brooks.

Article on the New York Times: Chinandega has been retaken, published on Feb. 7, 1927.

Book: The United States Marines in Nicaragua, by Bernard C. Nalty for the US Marines Historical Division.

Article USAF Air Chronicles: Sandino against the Marines, The Development of Air Power for Conducting Counterinsurgency Operations in Central America by Captain Kenneth A. Jennings (USAF).